Kennebec River Atlantic salmon restoration

One of America’s last wild Atlantic salmon populations now numbers in the dozens. But we have a chance at recovery.

BREAKING NEWS

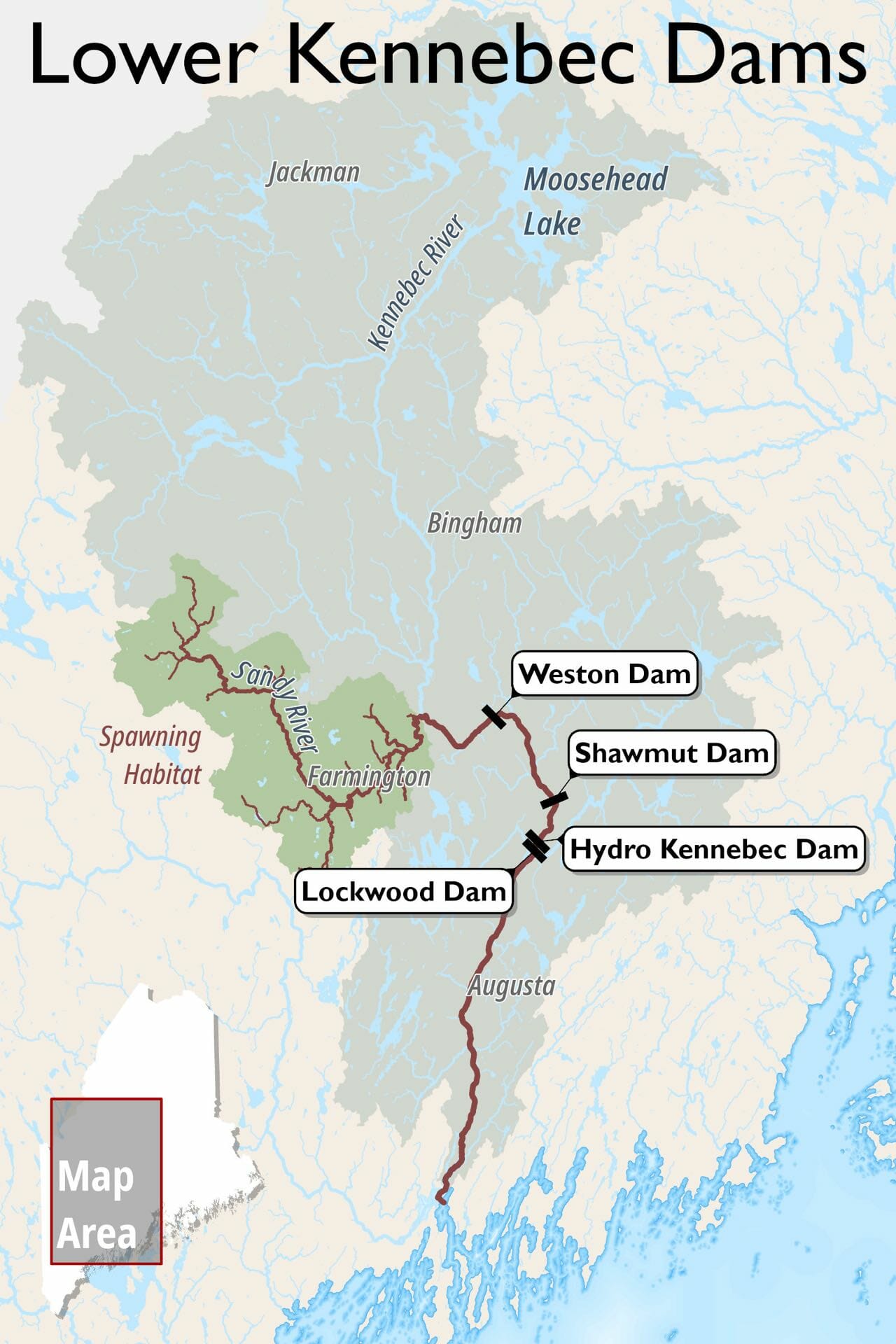

On Sept. 23, 2025, The Nature Conservancy and the owner of the four lowermost dams on the Kennebec River, Brookfield Renewable Partners, jointly announced an agreement that will set the stage for decommissioning and removing those four dams. The deal is scheduled to close in mid-2026, with the process of decommissioning and removing the dams expected to take about a decade. TNC and Brookfield are establishing a new entity, the Kennebec River Restoration Trust, to take ownership of the dams and to oversee their operation as the decommissioning and removal process unfolds. Trout Unlimited will remain engaged in this effort, which promises to be one of the most significant river restoration projects in history.

Stay up to date on the restoration of Maine’s Kennebec River

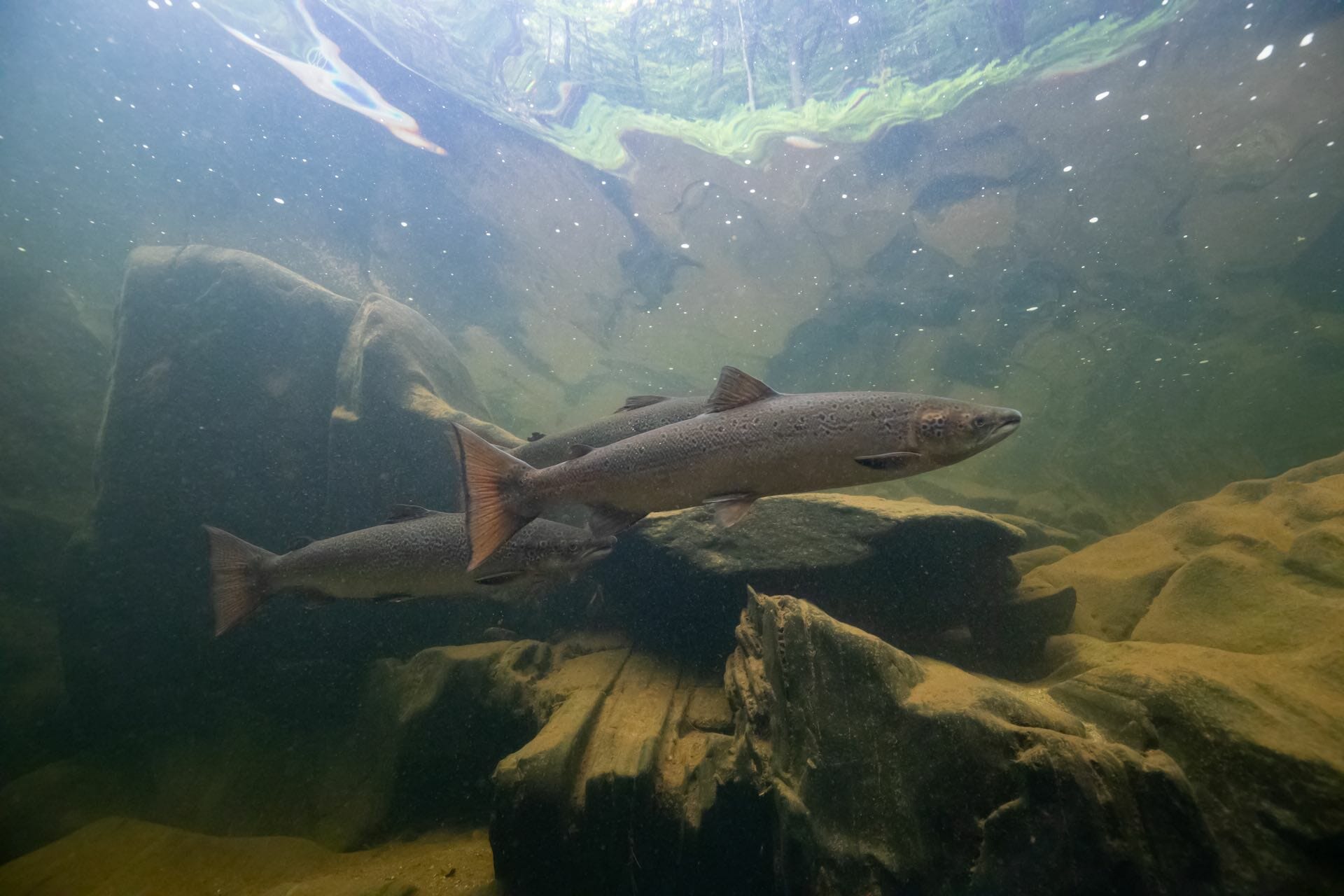

Two centuries ago, Atlantic salmon returned to Maine’s Kennebec River by the tens of thousands, with runs topping an estimated 200,000 some years. The fish supported important commercial and recreational fisheries, and were culturally and historically important to the Abenaki Tribe, who also relied on the species as a food source.

Today, returning salmon number in the dozens. Atlantic salmon in the Gulf of Maine were formally listed under the federal Endangered Species Act in 2000.

Like so many American rivers, the Kennebec suffered from timber drives and industrial pollution. But a primary cause of the decimation of populations of sea-run species like Atlantic salmon, American shad, river herring, sturgeon—and an ongoing hurdle to their recovery—is a series of dams that for decades have blocked the fish from critical spawning habitat.

Removing these dams offers the last best chance to keep Atlantic salmon from becoming extinct in U.S. waters.

Kennebec River: By the numbers

Length

Watershed size

Average daily discharge into Merrymeeting Bay

The last, best chance to save Atlantic Salmon in the United States

Numbers don’t lie. In 2018, only 11 Atlantic salmon were collected at Lockwood Dam, the first of the four barriers.

ELEVEN.

In an average year, just a few dozen adult salmon return. There, they are collected and trucked more than 50 miles to the Sandy River, a tributary that offers by far the best and most extensive salmon spawning and rearing habitat in the system. While the trucking program has been essential to maintaining at least a few salmon in the Kennebec, restoring the river’s once robust salmon runs means breaching the dams altogether.

In addition, such projects typically include the addition of in-stream structures to provide habitat for trout and other wildlife, including non-game species.

No other solution matches the scope of the problem.

The 1999 removal of what was then the lowermost dam on Kennebec River provides an encouraging preview of the impact of a free-flowing Kennebec. Built in 1837, the Edwards Dam spanned the river just above its tidal influence. After the dam came down, species including river herring, American shad and sturgeon returned in force to the nearly 20 miles of newly accessible habitat. In short, below Lockwood Dam, the Kennebec is a thriving river with rapidly recovering runs of sea run fish and all the wildlife that follows them.

The four lowermost dams on the Kennebec River are owned by Brookfield, a Canadian power company. The dams’ hydropower plants have a capacity of just 43 megawatts of electricity, around 6 percent of Maine’s 750 megawatts of hydro capacity. This small amount of energy production could easily be replaced by other forms of renewable energy, including the state’s increasing solar capacity.

The time is now for wild salmon on the Kennebec River

Shawmut Dam, the third dam in the series, is currently up for relicensing by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). As part of the process, the dam’s owners must prove that its fish passage and remediation plans sufficiently protect species that must pass through the dams. In the fall of 2022, the Maine Department of Environmental Protection denied Brookfield’s water quality certification application for the dam.

Fish passage infrastructure has failed to this point and will continue to be ineffective. The only way to recover the river’s endangered Atlantic salmon runs, one of the last in America, is to remove the fish-blocking structures.

News on the Kennebec River

- Conservationist dreaming of not catching shad

- Kennebec River dam owner dismisses state fish passage plan as counterproductive

- The Removal of One Maine Dam 20 Years Ago Changed Everything

- Kennebec River: Unfinished Business

- Brookfield Dam Operations on Kennebec strand and injure endangered Atlantic salmon

- Salmon deplete fat stores while stopped at dams, UMaine study shows

- NOAA biological opinion unrealistic for Kennebec River recovery