The moment remains etched in memory. We hiked in neoprene wetsuits pulled down to our waists because it was 85 degrees, but the rivers we snorkeled in were a LOT colder.

The stream, a tributary of the South Fork of the Salmon River in Idaho, was small, perhaps 10 yards wide. I recall how my mask made the stoneflies that tumbled by so large (and scary). I pulled myself around some deadfall and exclaimed an audible “whoa!” taking in a fair amount of water through my snorkel in the process.

Undulating in the stream before me were two steelhead. Beat up, bruised and ready to spawn. I thought about the 700 miles and 7,000 feet they climbed; the eight dams they traversed; the numerous predators (including us) they evaded—all in the service of returning to the stream they were born to spawn so that their species might continue.

Since then, when I was in my mid-20s, I learned of the cultural and spiritual significance of salmon and steelhead to Native Nations in the Northwest. I had elders tell me about how in the 1950s, before the construction of the four Snake River dams in southeast Washington, there was a two-month fishing season on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River in Idaho where anglers could keep up to two fish per day. I learned how salmon recycle nutrients from the Pacific Ocean into the nutrient “poor” mountains of Idaho.

Salmon and steelhead—these remarkable creatures of God’s creation, have dwindled to one to two percent of their historic numbers.

I have witnessed so much “WATH” thinking since that day I swam with those steelhead.

What About The Hatcheries? They can hurt wild salmon and steelhead.

What About The Harvest? Certainly, that can hurt salmon and steelhead.

What About The Habitat? It is no longer pristine after years of human development.

These WATHs can be, and often are, true. That said, it is the four lower Snake River dams that are killing our Snake River salmon and steelhead. But do not take my word for it. Here is what the fisheries scientists at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries said in a recent scientific report:

“For Snake River stocks, the centerpiece action is restoring the lower Snake River via dam breaching. Restoring more normalized reach-scale hydrology and hydraulics, and thus river conditions and function in the lower Snake River, require dam breaching. Breaching can address the hydrosystem threat by decreasing travel time for water and juvenile fish, reducing powerhouse encounters, reducing stress on juvenile fish associated with their hydrosystem experience that may contribute to delayed mortality after reaching the ocean, and providing additional rearing and spawning habitat.”

The four lower Snake River dams produce 140 miles of bathwater warm, predator laden reservoirs that simply put, kill salmon—especially the smolts that used to be flushed downstream. There is no flushing spring freshet in a reservoir. Instead, in a journey that used to take a few days and now takes weeks, the smolt are eaten, succumb to high water temperatures or are so weakened when they reach the estuaries of the ocean, that they perish.

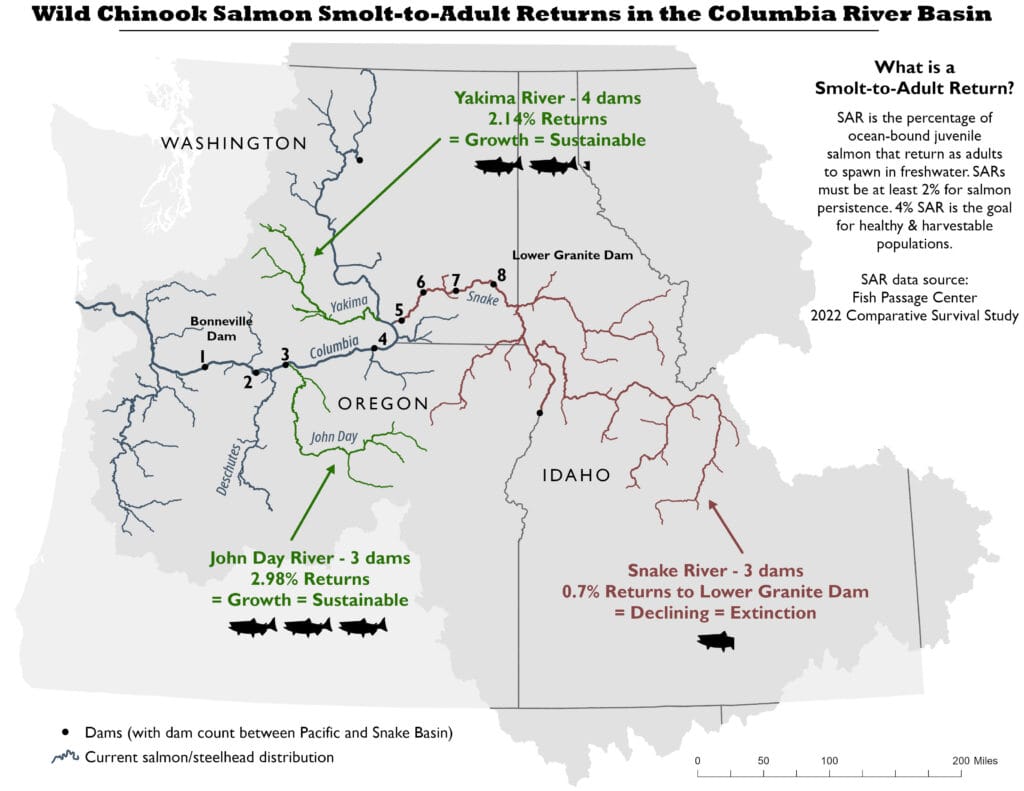

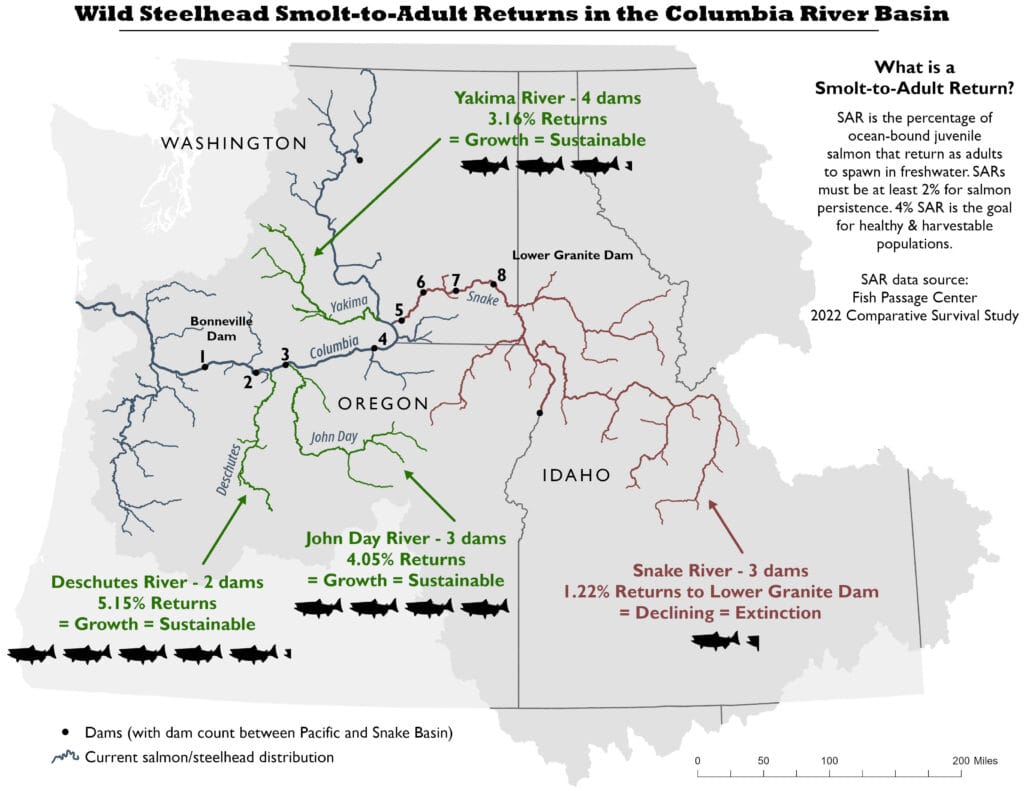

To understand the practical effect of the eight dams Snake River salmon and steelhead must pass, look to two other basins in the Columbia River Basin. Chinook salmon in the Yakima River in Washington, for example, pass four dams and for every 100 smolts that make it downstream, 2.1 adults return. On the John Day River in Oregon, Chinook salmon pass three dams, and for every 100 smolts that make it to the ocean, 2.98 adults return.

Fisheries scientists tell us that at least two adults must return for every 100 smolt that make it downstream to have a sustainable population. On the Snake River, for every 100 wild spring/summer Chinook salmon smolts that make it downstream, .0.7 adults make it back after passing eight dams.

The Snake River Basin has the highest quality habitat for salmon and steelhead in the lower 48. Forty percent of the basin is either wilderness or roadless areas. It is a five-star hotel, but the guests cannot get there because of the four lower Snake River dams.

Something will have been lost from our humanity if we allow Snake River salmon and steelhead to slip into extinction; their wonder-inspiring, almost magical ability to return to their birth streams, spawn, die and the fact that their decaying bodies provide the nutrients to keep these ecological systems intact. The salmon depend on the rivers, and the rivers depend on the salmon. Can we possibly turn away from the salmon’s sacred importance to tribes and their commercial importance to coastal communities (and potentially, once again) recreational anglers?

Like the person who chose not to stop a bully from picking on a smaller kid, will we walk away as a nation knowing we could have intervened, instead of sitting on the sideline and watching that kid get beat up?

What a loss. What a stain to humanity. We can replace every single social and economic benefit provided by the Snake River dams. Every single one. We can replace the three percent of the region’s power the dams provide. We can use rail instead of barges to move grain from eastern Washington. We can extend pipes for irrigators who depend on the reservoirs.

But the salmon and steelhead? They need a river.

Let’s work together and make sure they get one by taking out the four lower Snake River dams.