DIY anglers have only regulations and their own consciences to follow

We made the agreement long before we headed north. We were driving down a highway in Wyoming’s Bighorn Mountains, recapping our recent fishing trip (for tiny brook trout) and planning the next one (for monster bull trout).

“If we have any luck finding bull trout, we should each catch one and then be done,” I told my husband, Josh.

“I don’t think that’s going to be a problem,” he said.

“But still,” I argued. “I want to put out there that we don’t need to hammer a fish like bull trout. One and done, fair?”

“Fair,” he said.

We were going to British Columbia to try to catch a species that was once not hard to find and now, because of overfishing, climate change, logging, pollution and habitat fragmentation, is much trickier, especially without a guide.

I wanted us both to be on the same page, that catching a species as unique, and in places as imperiled, as bull trout didn’t need to happen more than once.

Weeks later, in a cold, clear, glacier fed river that wound through an old burn scar surrounded by bright pink fireweed and knee-high saplings, Josh caught a beautiful, silver bull trout. We snapped a few quick pictures, and he slipped the hook out of the fish’s mouth and released it back in the water.

It was one thing for him to make a deal with his spouse weeks ago in the abstract, and another thing to recognize that one and done meant on day two he would be switching from swinging big streamers to being on dog and kid duty while casting to much smaller Westslope cutthroat.

The deal we struck wasn’t part of a regulation. British Columbia closes streams the province feels can’t handle pressure and limits take in other areas. We weren’t resolving to follow the rules—we are consummate rule followers—we resolved to do what we felt was right in that dusty gray area where almost all hunters and anglers reside.

And when we’re out there by ourselves, with no guide to tell us where to step (or not step) or to pinch our barbed hooks, or to tell us not to play a fish so long, it’s up to us.

“A peculiar virtue in wildlife ethics is that the hunter ordinarily has no gallery to applaud or disapprove of his conduct,” wrote famed ecologist Aldo Leopold. “Whatever his acts, they are dictated by his own conscience rather than by a mob of onlookers.”

The same applies to fishing. It’s up to us to decide how to act when we are our own audience.

Reading the Water

The Gray Reef section of the North Platte River wending through central Wyoming is one of those blue-ribbon tailwaters with lots of private water for guides but still enough public stretches to keep the rest of us happy. It’s not a native trout fishery—before dams the North Platte’s cool water ran thick with channel catfish, shovelnose sturgeon and sauger. But a series of reservoirs, habitat improvements and years of stocking made it into a destination rainbow, brown and cutthroat fishery.

Regulations only let you keep one fish over 20 inches, effectively rendering it a catch and release only fishery, albeit one that lets you huck three flies, barbs intact.

And the effectiveness of patterns like San Juan worms or pegged beads with big hooks under strike indicators is starting to take its toll.

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department recently surveyed fish populations for hook scarring and found that at high levels, even practices we all thought were fine aren’t actually fine.

“We’re starting to see some pretty sobering data,” said Matt Hahn, one of the department’s fisheries supervisors. “I think we’ve crossed the threshold now where catch and release angling is having a real impact on the population.”

The department is looking into what they could potentially do with regulations to help this growing problem, but Hahn also said there’s only so much.

“The best would be to reduce the number of injuries to fish, and the easiest way to do that would be to lower the number of fish being caught through tackle restrictions and seasonal closures,” he said.

While regulations have a proven track record of helping species and ecosystems come back from the brink, there’s also plenty we can do on our own when water temperatures are too hot, when we pull up to a river access and combat fishing is the first term that comes to mind, or when we want to pump the oars of our raft or boat backward to strip through a hole once more.

And here’s the thing, while self-regulation might sound like a bummer, it doesn’t need to be.

Finding Middle Ground

Josh may have caught his one and only bull trout on the second day of a weeklong trip, but looking back, he doesn’t feel he was shorted of experiences on the water.

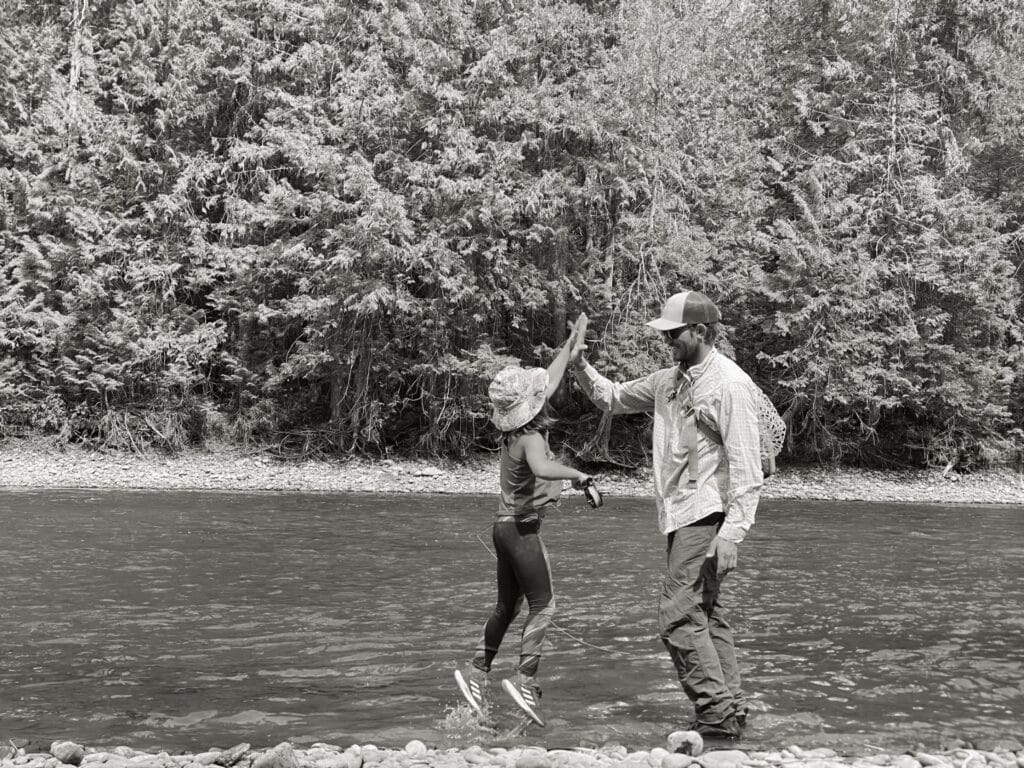

He helped our 7-year-old daughter catch her first whitefish. He caught rising Westslope cutthroat trout on dry flies and he stood by my side while I slipped the hook out of my first bull trout’s mouth and released it back into the water.

Sometimes, when we’re the only ones out there, it’s a question of reframing what we’re there for.

“Maybe you don’t need a picture of every fish you catch that’s over 15 inches. Take a picture of the sunset instead,” Hahn said. “Or take a cool picture of a mayfly on your reel.”

And it’s also far from as simple as catching one fish and heading home. Sometimes it’s about considering your past experiences and what you really need out of this particular one.

Hahn spent his life catching plenty of fish; he doesn’t really need to have 30-fish days anymore. He also readily admits that if he was in a boat, floating a stream and his teenage son finally had it dialed in and was catching fish after fish, he’s not sure he would tell him to stop. Not right away anyway.

So maybe the next time we’re out there and we’re catching fish on every cast, we can congratulate ourselves, then we can switch up our flies. Try something strange we don’t think will work and see how the fish will respond. Spend a couple beats longer watching an eagle or a heron or a king fisher.

We can also acknowledge there are places that could use more fishing and could benefit from more anglers taking fish home. Maybe leave that trophy trout fishery after netting one or two and head to streams with stunted brook trout where biologists plead with anglers to catch and keep six or even 12. Fillet them back at camp, season them with a little salt and pepper and enjoy the fruits of your labor for dinner. Better yet, use your extra time on the water to target those fish no one thinks about, the red-eye bass, chiselmouth or bowfin.

Pinch your barbs. Use smaller hooks. Find a run with no one in it even if it looks like it won’t be quite as good. Don’t take a picture of every fish, and release them as quickly as you reel them in. When water temperatures increase during the heat of summer, fish in the early morning, head higher up into the mountains where the temperatures are cooler or target warmer water species in a lake or reservoir.

Few of these ideas you’ll find reflected in regulations, though some states and national parks are beginning to require barbless hooks, single flies and closing streams during heat of summer.

Instead of waiting for a guide, biologist or regulation to tell you what to do, think about the fishery and use your conscience to guide you.