Executive summary

Fishing for trout is a passion shared by countless anglers across the country. The challenge of catching a monster Lahontan cutthroat trout from Nevada’s Pyramid Lake or a salter brook trout from a coastal stream in Massachusetts can be rewarding and frustrating all at the same time. As fly-fishing author John Gierach described it, “If people don’t occasionally walk away from you shaking their heads, you’re doing something wrong.”

The beauty and diversity of trout attracts the artist and photographer as well as the angler. Not only are the fish themselves works of art, but they occur in some of the most beautiful settings the country has to offer, from small gurgling country streams to high-mountain lakes to sweeping western rivers.

Unfortunately, neither the status of native trout nor their habitat is secure. During the past century, trout have declined as a result of land development, overfishing, water pollution, poor timber and livestock grazing practices and the introduction of non-native fishes and other aquatic invasive species. Stocking of hatchery trout has swamped the genes of the native trout through hybridization and competition.

Trout now face an evolution of these threats. Human population expansion has increased the demand for clean water, with more water diverted for municipal, agricultural and energy development. As our population expands, so does the demand for energy with new facilities invading prime trout country and the proliferation of hydraulic fracturing techniques that require 2 to 8 million gallons of water per well. Add to these the growing threat of climate change, which not only is warming the cold-water habitats trout depend on, but also appears to be compounding many of the traditional problems trout face. In the face of climate change, our wildfire season is longer and fires are larger and more intense; droughts and flooding are more severe. Non-native species, including warmwater fish like smallmouth bass and carp, are spreading into what was prime trout habitat.

This report details the status and trends within 28 separate species and subspecies of trout and char that are native to the U.S. Trout naturally occur in 38 of the 50 United States. Not included in this report are grayling, whitefish or the ocean-going steelhead and salmon, which will be described in a future report. Alaska will also be treated in a later report.

Of 28 native trout species and subspecies, three are extinct and six are listed as threatened or endangered. Excluding the extinct trout, 52 percent (13 of 25) occupy less than 25 percent of their historical habitat and are at high risk from at least one major threat. Nearly all native trout — 92 percent — face some level of risk.

We divide our analysis into 10 large ecoregions: Pacific Coast, Central Valley/Sierra Nevada, Interior Columbia/Northern Rockies, Interior Basins, Southern Rockies/Colorado Plateau, Southwest, Great Lakes/Upper Mississippi, Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, and Southeast. Trout status, threats and success stories of how to deal with these threats are described within this regional context.

Widespread populations, genetic diversity and flexibility in life history expression has maintained trout over the eons and helped them adapt to changing conditions. But now, the loss of diversity, including genetic, life history and geographic diversity, threatens the persistence of most native trout species and subspecies. Not surprisingly, most trout face multiple threats, with two of the most common and serious threats to native trout —non-native species and climate change—now acting in tandem to degrade trout habitat and encourage the spread of non-native species.

If future generations of Americans are to continue to reap the recreational and economic benefits of abundant trout populations, we must chart a new path forward. As described in this report, we have the knowledge and tools to deal successfully with current and emerging threats and to restore robust populations of native trout. The question is not whether we can restore native trout but whether we choose to do so. Trout Unlimited is dedicated to helping society make the necessary changes to implement the following steps.

- Work at watershed scales to protect remaining high-quality habitats, reconnect fragmented stream systems and restore degraded mainstream and valley bottom areas. This will not only help restore fish populations but also improve the storage and delivery of water supplies during times of drought and flood.

- Train volunteer leaders and the next generation of conservation stewards so that our work to protect, reconnect, and restore wild and native trout populations will persist over time.

- Work to rebuild large, interconnected populations of native trout, which would facilitate restoration of life history diversity and create populations that are resilient to climate change. This approach not only offers some protection from climate extremes but provides opportunities to conserve entire communities of rare aquatic species.

- Become smarter and more effective in our restoration efforts. Restoration shouldoccur at large scales, incorporate local climate change impacts and must be monitored and sustained over time.

- Control the introduction and spread of non-native plant and fish species and minimize or eliminate trout hatchery stocking programs in the vicinity of native trout populations.

- Become more efficient in our use of energy resources and the water that is required and make sure that energy development does not impact high-value fishery resources.

- Conserve water resources and become more efficient in the water that our agricultural practices, cities, and factories use so that we can build more sustainable communities.

- Increase angler participation in habitat restoration, monitoring and policies that affect fishery resources.

Ultimately, the human condition is inextricably linked to the status of native and wild trout populations. We all depend on high-quality water in stable supply, not only for our cities and agriculture, but for our recreation and spiritual sustenance. Native and wild trout are sensitive to pollution and degraded water quality, so their sustainable populations are good indicators of the health of our rivers and their watersheds. All the more reason to make sure we maintain vibrant, fishable trout populations for our current generation and those yet to come.

The values of sustainable fisheries to our lives are sometimes hard to quantify but are well described in the following passage by Robert Travers.

I fish because I love to; because I love the environs where trout are found, which are invariably beautiful, and hate the environs where crowds of people are found, which are invariably ugly; because of all the television commercials, cocktail parties and assorted social posturing I thus escape; because in a world where most men seem to spend their lives doing things they hate, my fishing is at once an endless source of delight and an act of small rebellion; because trout do not lie or cheat and cannot be brought or bribed or impressed by power, but respond only to quietude and humility and endless patience; because I suspect men are going along this way for the last time, and I for one don’t want to waste the trip; because mercifully, there are no telephones on trout waters; because only in the woods can I find solitude without loneliness; because bourbon out of an old tin cup always tastes better out there; because maybe one day I will catch a mermaid; and finally, not because I regard fishing as being so terribly important, but because I suspect that so many of the other concerns of men are equally unimportant — and not nearly so much fun.

[…]

The path forward

This report describes the many and varied threats facing native and wild trout in this country. Threats have evolved over time, from agriculture and mining practices of the past to a new suite of problems related to four primary issues: energy development, introduction of non-native species, increasing water use and demand, and climate change. Legacy problems remain in many areas and their impacts are compounded by these emerging challenges.

There is good news as well. The practice of restoration is becoming a mature science with more effort dedicated to stream restoration each year. At TU our efforts to protect, reconnect and restore the habitat of trout grows annually. In 2014, TU volunteer members donated more than 650,000 volunteer hours to more than 1,050 restoration projects and more than 1,550 environmental education projects. Altogether, more than $1 billion is spent on stream restoration each year in this country. This number increases significantly if recovery efforts for Threatened and Endangered species such as Lahontan cutthroat trout, Apache trout and bull trout are included.

As we describe in the report, there are major success stories in each region. State and federal agencies dedicate sustained effort towards monitoring and improving the status of native and wild trout. These agencies have developed and signed conservation agreements for the rarer native trout species and organized active workgroups to implement these efforts. In 2014, for example, the Interior Redband Trout Conservation Agreement – an agreement describing commitments for restoration of interior redband populations — was signed by three federal agencies, six state fish and wildlife agencies (all states within the historical range of the subspecies), five tribal governments and Trout Unlimited. These same agencies will track implementation progress and modify the agreements as conditions change.

Despite this dedication from agencies and anglers alike, the current suite of problems affecting native and wild trout cannot be addressed adequately by strategies and actions of the past. An improved knowledge base must be brought to bear on the conservation challenge and new strategies, tactics, and capacity developed to implement an enhanced effort.

Anglers can be a potent force for trout conservation and their numbers represent a vast resource for conservation. Many anglers are close observers of on-the-ground conditions for trout, their habitats and emerging threats such as the spread of invasive species. Many anglers are becoming citizen scientists, adding their observations to the growing public participation in scientific observation and research. As anglers learn more about the streams they love, they become stronger advocates for improved resource management. TU takes a unique approach to this, dubbed Angler Science, and our programs have a particular ability to focus the passion of our angling members toward doing meaningful science in support of the fish and the landscapes that they love. Today’s mobile and online technologies combine to provide new opportunities for citizen scientists to capture important data that can instantly be documented with photographs and GPS locations on-the-spot.

ENERGY DEVELOPMENT

Over the past several decades the demand for energy resources has grown and has been accompanied by an unprecedented increase in oil and natural gas production as well as renewable energy development. More states are passing renewable energy portfolio standards requiring a greater use of renewable energy resources. Oil and gas development has pushed into new territory and the increased use of chemicals and water for hydraulic fracturing has resulted in higher water demand. Pipeline failures have damaged iconic rivers such as the Yellowstone. Renewable energy development is spreading on public and private lands with increased road networks and sedimentation of stream systems. Oil, gas, wind and solar development have moved onto large tracts of National Forest and BLM public lands.

Sportsmen and women have worked to discourage or prevent energy development on public lands containing high quality streams and high priority trout restoration areas such as the Wyoming Range in Wyoming, the George Washington National Forest in Virginia, the Rocky Mountain Front in Montana and the Roan Plateau in Colorado. Trout Unlimited assists such efforts through public awareness campaigns and development of an ecological footprint assessment locating those areas with the greatest concentration of people and resource disturbances and encouraging energy development there as well as in areas with already compromised natural resource values rather than in higher quality natural areas.

On public lands in the West, such as the White River National Forest, we are actively working with energy companies to site energy development to minimize effects on trout. In parts of the East where shale gas is being developed with hydraulic fracturing technology, state agencies are teaming with angler-scientists to track potential water pollution problems in brook trout streams. With the expansion of hydraulic fracturing, which may require 2-8 million gallons of water per well, a better understanding of how energy development is likely to impact surface and groundwater resources is needed so that we can ensure adequate water remains instream for aquatic life and other human uses. Funding to mitigate impacts of energy development is needed and would be provided by the bipartisan Public Lands Renewable Energy Act now pending in Congress.

NON-NATIVE SPECIES

The interconnected nature of most aquatic habitats renders them particularly vulnerable to the introduction and spread of non-native species. Once introduced, some non-natives can readily spread throughout entire river drainages. Historically, stocking of non-native trout has been one of the greatest threats to native trout as species such as brown trout and hatchery-produced rainbow trout compete with, prey on, or hybridize with native species. More recently, invasive aquatic invertebrate and plant species are a growing problem, with anglers, boaters and other recreationists unwittingly assisting with their spread as they and their equipment move from one drainage to the next. Also, as waters warm from climate change, species such as smallmouth bass, carp and catfish invade former trout habitat as temperatures increase. Programs urging or requiring recreationists to inspect, clean and dry waders and other angling equipment, as well as boats and their trailers, can help stop the spread of aquatic invasive species.

Traditionally, many agencies have sought to isolate native trout in small headwater streams by constructing instream barriers to prevent contact with downstream invasive species. Unfortunately, this strategy can restrict native trout to isolated areas where they are increasingly vulnerable to flood, drought, or wildfire. Better balanced trout management strategies should maintain larger, interconnected stream systems and large lakes as well as isolated headwater streams. That means we need new methods to better understand and track the presence of non-native species and better ways to control and eliminate them once they are found. Improving technology may help in this area. New tests for “environmental DNA,” or “eDNA,” can detect the presence of different species simply by identifying their DNA from samples of the water where they occur. In this way, brown trout could be detected in, or confirmed absent from, waters by tracking their shed skin, mucous, or secreted feces, without ever seeing a fish.

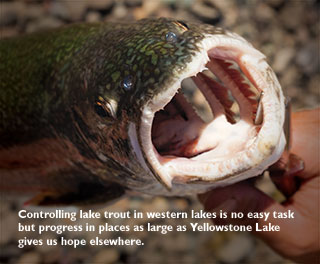

We are finally gaining the upper hand in the battle to control non-native lake trout in Yellowstone Lake and other parts of the West where they have been introduced to the detriment of native trout populations. The National Park Service, aided by U.S. Geological Survey, Trout Unlimited and others, have netted hundreds of thousands of lake trout annually in recent years and the population of this non-native predator in Yellowstone Lake appears to be in decline. In addition to netting programs, biologists now track lake trout to spawning areas where eggs can be targeted by electrofishing or sonic pulses. Controlling lake trout in western lakes is no easy task but progress in places as large as Yellowstone Lake gives us hope elsewhere.

We also may be able to control some non-native species by restoring more natural streamflow regimes, including high spring flows and improving riparian and channel conditions that can cool water and reduce the threat from warmwater fishes. Research and development of novel ways to control non-native species should be a high priority.

WATER USE AND DEMAND

Demand for clean water is increasing as our human population continues to grow, especially in many parts of the West where water supplies are naturally scarce. Large western urban areas have tapped deeply into traditional sources of groundwater and over-allocated rivers. Some cities, like Las Vegas, are reaching as far away as the Utah-Nevada border for municipal water and affecting habitats for Bonneville cutthroat trout as traditional sources of water from Lake Mead and the Colorado River decline. According to a recent EPA study, the April snowpack has declined across three-fourths of the western states since 1955. Most of California and the Interior Basins are currently in a severe drought and much of the Southwest is predicted to see more severe droughts than any yet experienced in this region since humans began recording history. This dire forecast demands immediate action to protect our aquatic resources and native trout.

One way to improve stream flows is by working with the agricultural community and irrigation districts to improve irrigation efficiencies. Nationwide, water withdrawals for agriculture amount to about 40 percent of all water diversions (only thermoelectric power operations use more). Water supports agricultural production but gains in efficiencies can benefit natural systems while maintaining important food production. One recent example of success in this effort is in Washington’s Methow Valley, which is home to both salmon and agriculture. Trout Unlimited and the Methow Valley Irrigation District recently reached agreement to leave 11 cfs in 3.5 miles of the Twisp River by eliminating the Twisp River Diversion and replacing it with a pump on the Methow River.

Restoration of natural watershed function – the capture, storing and slow release of precipitation – can maintain more water in headwaters and help recharge shallow groundwater aquifers. Natural watershed function will improve from restoration of wetlands, high elevation wet meadows, riparian areas and floodplains. These habitats are critical to capture precipitation, modulate runoff, replenish groundwater aquifers and slowly release water to improve late-season stream baseflows. Trout Unlimited and California Trout work closely with the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation on an innovative program designed to restore wet meadows in California’s drought-stricken Sierra Nevada.

Water conservation is the third leg of our approach to water demand. Not only must we become more efficient in our use of water but we need to use less, especially in areas where valuable natural resources such as threatened trout populations are at risk. The biggest potential for water conservation is in agricultural operations, which can use less water simply by switching irrigation methods, from flood-irrigation to drip lines, for instance. Each of us can help reduce water use in our daily lives, as well.

CLIMATE CHANGE

Climate change is likely the greatest threat faced by native and wild trout, yet it is difficult to isolate and define because many problems already facing trout are compounded by the effects of climate change. For example, as winter snowpack decreases and forest moisture levels decline, the severity, extent and intensity of western wildfires are increasing. As storms in the Northeast U.S. become more severe, the impacts of floods and stream sedimentation increase. Increasing summer temperatures are, of course, a particularly significant problem for coldwater-dependent trout. Available trout habitat decreases while invasion by more warmwater species increases.

The problems associated with climate change must be approached on several levels. The good news is that many traditional approaches to stream and riparian area restoration also help alleviate impacts associated with climate change and make fishing better. Protecting headwater sources of cold clean water is crucial. Reconnecting streams to floodplains and widening riparian reserves and increasing shading by trees will diminish flood damage and help keep streams cool, respectively. The problems are so severe that effective restoration needs to occur at larger watershed scales to be most effective in reducing climate change impacts. Similarly, as described for Maggie Creek in the heart of Nevada, progress can be made in securing water supplies and making stream systems resilient to increasing disturbances despite drought conditions. The current degraded status of many of our streams leaves opportunity for widespread gains through restoration that will offset climate change impacts.

Perhaps most importantly, we must slow the rate of climate change by reducing our fossil fuel consumption and greenhouse gas production. Energy policies should encourage reduced energy consumption with a preference to renewable forms of energy.

As policy decisions and shifts to more renewable forms of energy move forward, fisheries managers must continue to adapt to increasing impacts of climate change. If we’re smart, we make communities safer from wildfires and floods, while simultaneously improving habitat conditions for wild and native trout. Stream restoration projects must integrate local climate-related effects to the scope and implementation of their projects. Projects to reduce flood, drought and wildfire damage should rely more on holistic solutions that benefit rather than degrade natural systems. Culverts of greater capacity can be designed for increased flooding and rivers reconnected to their floodplains where high flows can naturally dissipate their energy by spreading out across the land.

Improved monitoring of stream temperatures and flow are critical if we are to fully understand the scope of the problems and potential solutions. Existing water monitoring programs of the U.S. Geological Survey should be expanded. Anglers and other citizen scientists can play an important role in monitoring changing stream conditions and filling in gaps in agency monitoring programs. The U.S. Forest Service has demonstrated the importance of landscape scale monitoring of stream temperatures through their development of the NorWeST project, which collects, displays and analyzes stream temperature data from across the Northwest and Interior Basins. Recently, these data have been used to predict specific stream systems that are likely to maintain their cold water through the 21st Century. These areas form a “climate shield” where efforts to conserve cutthroat and bull trout are most likely to succeed. TU is partnering to expand this work to areas with a critical need for stream temperature information, like the Lahontan and Bonneville regions of the Great Basin. Large temperature databases are also being assembled for the Northeast as part of the NorEaST project.

Individual anglers can make a difference as well by changing their angling practices and lifestyles. Catch and release practices can be improved by minimizing handling stress and minimizing the time that fish are held out of water. Where stream temperatures are stressing trout, angling should be avoided. Anglers can change their personal habits to increase water conservation and decrease energy use. Finally, anglers can leverage their collective passion and know-how by joining organizations such as Trout Unlimited that are working toward a more positive future for trout.

Ultimately, the human condition is inextricably linked to the status of native and wild trout populations. We all depend on high quality water in stable supply, not only for our cities and agriculture, but for our recreation and spiritual sustenance. Native and wild trout are sensitive to pollution and degraded water quality, so their sustainable populations are good indicators of the health of our rivers and watersheds. All the more reason to make sure we maintain vibrant, fishable trout populations for our current generation and those yet to come.