by Toner Mitchell

Editor’s Note: This post was first published on July 23, 2018, on the TU blog.

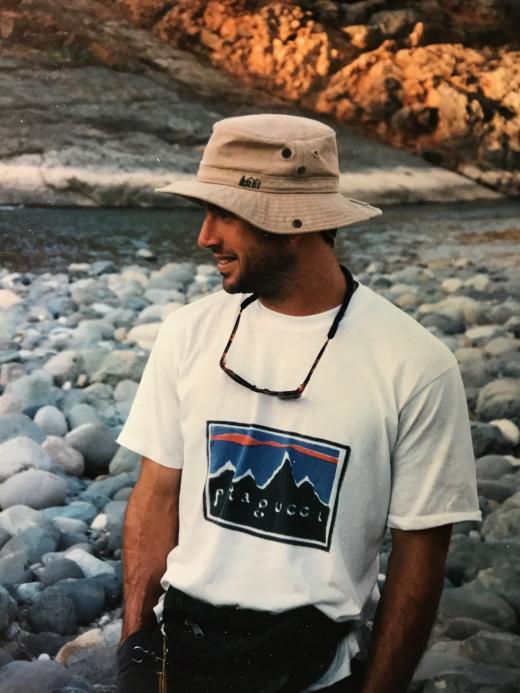

Gordon Becker was in love with nature for as long as anyone can remember. He climbed it, hiked it, fished it, and boated it. After earning a master’s degree in fisheries biology, he built a career out of studying it and fighting for it from office chairs, rafts, and seats around countless campfires. In his last several years of life, it became clear that whatever he did, successfully or in error, was driven by his devotion to rivers and salmonids.

His main focus was on the restoration and protection of steelhead and salmon in the urban watersheds around San Francisco Bay. In all things, he was known for speaking truth to power. I was proud of his work on the improvement of streams like Pescadero Creek, Alamitos Creek, San Francisquito Creek, and the Carmel River, just as I was annoyed with him calling bull on his pals for their overconsumption of toilet paper and other minor infractions. I also admired how he applied his rigid principles to himself; he took himself to task for misreading his own instincts and for withholding his empathy from people he knew deserved a fairer shake. Among all the people I have known, including myself, Gordon was outstanding in this regard.

Last week, two of his childhood friends and five others from college – after reaching a point in our grief where we remembered more of his life than of his death – embarked on a mission to take him home. Where he belonged, to the high Sierra Nevada where his love affair with nature was born. I dreamed that his ashes would someday be incorporated – physically and molecularly – into the body of a steelhead, that soon he would swim again, then die again, and be born once more.

My fear was at the other end of the universe. What if he didn’t make it? Our trek was through the drainage of the San Joaquin River, perhaps the most used and worn out river in the West. En route to his heaven, Gordon would flow down to jet ski-shredded Shaver Lake. He’d serve penance on a Fresno golf course after a tour in a sewage plant. No doubt he’d spend centuries on an almond grove, and if by some miracle he finally reached the delta, he might get sent south through a canal for another round.

After 21 grueling miles of backpacking, however, these fears instantly evaporated at the sight of Mount Darwin and the snow cold, golden trout-filled waters of Evolution Lake. This was no epiphany, just my logical realization that, whether or not humankind ever comes to its senses, Gordon will complete his journey downstream through an infinite array of possible courses. The Sierras, in their youth still displaying the scratches and carvings of their rise, do that to you, or at least they do it to me. They embody a past without a beginning, a future with no end. Gordon will have plenty of time.

At the lake, infinity became a source of comfort and rejoicing even as I knew the hole that Gordon left in me will never be filled. Yes, I still wished he could become his spirit animal, but in a way I know he already has. I know absolutely that many salmon, steelhead, and their ecosystems are alive and have a good chance of surviving as a result of Gordon’s life.

Heraclitus believed that we can never step into the same river twice. My own version of this statement is informed by our journey to Gordon’s new place: We can never see the same trout as we did the second before. In that second, there are minute changes in the quality and angle of light upon the fish, which cause scales to reflect a limitless array of hues. I believe this to be as true as it is imperceptible, and it finally explains my lifelong obsession with the cheeks of trout, how they seem to change before my eyes in spite of my capacity to measure how.

From now on, though, it will please me to no end that my communion with fish will be with this understanding and, given how it came to me, with Gordon at my side. From now on, he will be the ever-changing light and color, the color within the color. Again, it’s the infinity thing.

I’ll see you there, my wonderful friend. Until then, happy trails.

Toner Mitchell is New Mexico project coordinator for the TU’s Western Water and Habitat Program.