Returning to the valley a year after surgery.

The way I figure it, they probably stopped her heart around 1 p.m.

The bypass machines kicked on and in my mind they sounded like the soothing white noise of a ceiling fan. Peaceful. I don’t know if a person subconsciously takes in any noise during surgery, but for her sake I hope it was calming.

A few months prior they found a hole in her heart the size of a dime. Routine six-year-old checkup. The pediatrician spent a little more time than usual listening to her heart. Sit up. Lay down. Breathe in. And exhale. Let’s do that again.

“Has anyone ever told you she has a heart murmur?”

“No,” I said.

“Probably nothing, but better to be sure.”

During the echocardiogram the technician was silent and evaded my gaze.

Three months later we were in Seattle, pressed against the glass of an ICU breakroom as they wheeled her by, still as dread, a speck of a child on a white field of hospital sheets.

A few hours down the road from our house is a big, wide valley. On one ridge the Continental Divide continues its march from the southern border to the northern. The other gives way to a sloping range of wildflowers and timber.

In the middle is a series of small streams full of brook trout, cutthroat trout and of all things, grayling, who migrate up from the lake below.

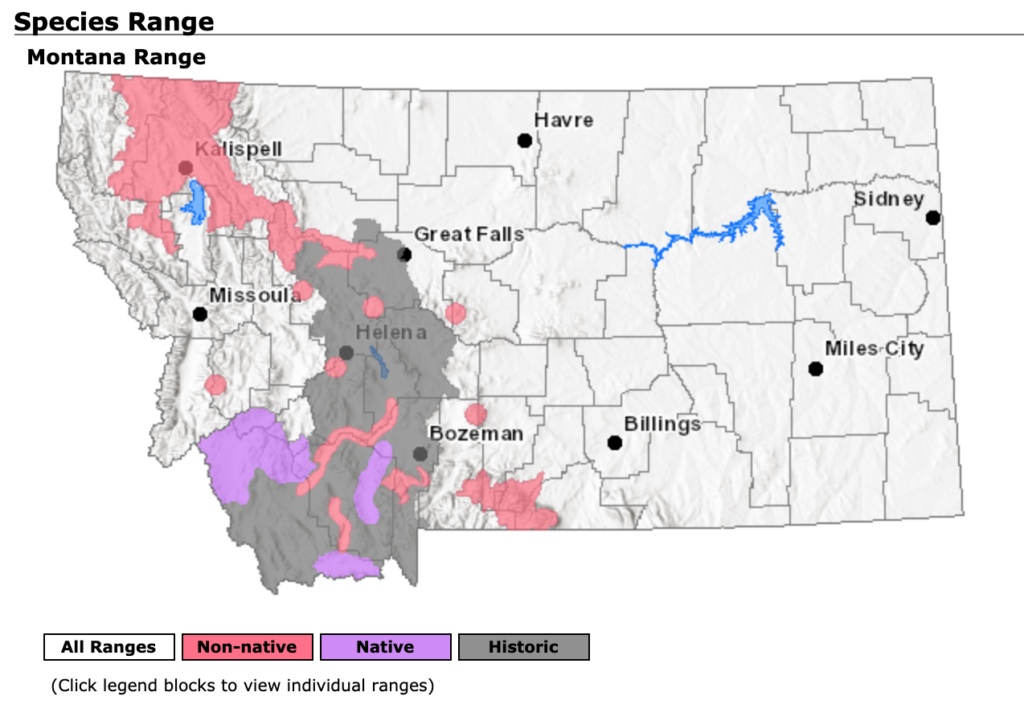

Montana is one of two places in the lower 48 with native populations of arctic grayling, with both adfluvial (lake dwelling) and fluvial (river dwelling) populations. At one time Michigan was the other, although those populations have since gone extinct.

These fish are relics leftover from the glaciers – pre-historic in origin and appearance.

The summer we learned about her heart, we didn’t fish much. We didn’t do much at all. At the time we made excuses about too much work and saving vacation time, but in truth I think fear has the effect of freezing your feet in place, even feet that have spent every other summer on the move.

Somewhere in there, we found our way to this valley for an afternoon.

By mid summer the grass reaches your waist and the willows are so thick they form a barrier around the stream, providing minimal access except at the occasional bend.

The stream is clear and so cold one must pause on the bank to consider the repercussions of wet-wading before stepping in. I had left both kids behind to eat dinner, needing a bit of space to reset.

Repairing the hole in her heart had been considered a priority but not an emergency and she had been scheduled to go to Seattle at the end of the summer. So we waited. With impatience. With dread. Waited simultaneously counting and cursing the days that passed.

Pushing past the willows and forward to a deep hole I pulled a small cutthroat from the waters. Then another. Maybe even another. I don’t really remember.

What I do recall – vividly – was the flash of silver. A grayling. As old as the dirt in the streambed. And though I can’t explain why, it felt like a reminder that life is simultaneously a short and long affair. That it should be lived well and hard and that some things carry on seemingly forever.

And with that, I tied up my fly rod, pushed through the willows, and walked back to my family.

There are things modern medicine prepares you for and there are things it does not.

Wound care. Activity restrictions. Proper administering of medication.

That is only part. The rest is in your head.

Not surprisingly, it starts with fear — fear that the solution is not as straightforward as a team of pediatric cardiac surgeons says it is. That cracking open a 6-year-old’s chest, stopping her heart and sewing it up again with something akin to Gore-tex, while routine to them, is really not routine.

Fear, in this scenario, seems a natural reaction.

But once that is gone — and it passes quickly — and your daughter is back to bouncing off the walls, teasing her brother and jumping on the picnic table to moon you with her pale little butt waving around in the sun a week after open-heart surgery (yes, that really happened) there is an odd sensation of guilt. Guilt that you got to walk out of a children’s hospital filled with babies and parents who don’t get to walk away practically whole, as you have. What happens to them?

This does not pass as fear does.

Perhaps least expected yet longest lingering is the anxiety. The dread that the luck you had will someday soon run out. The habits you put in place to reduce the risk life just doles out will not shelter you and pretty soon you realize you can’t control any of it not matter how you try.

Her one-year anniversary is this week. I don’t know what one does for such occasions except offer great gratitude to the universe and send grace to all those families who are finding their own way through hope or grief.

Maybe you go fishing. Place yourself in the cold water of a river and the dirt of centuries past and feel it move past you. Remember that all life evolves. Over eons, the best things persist and all you can do is let the rest of it go.