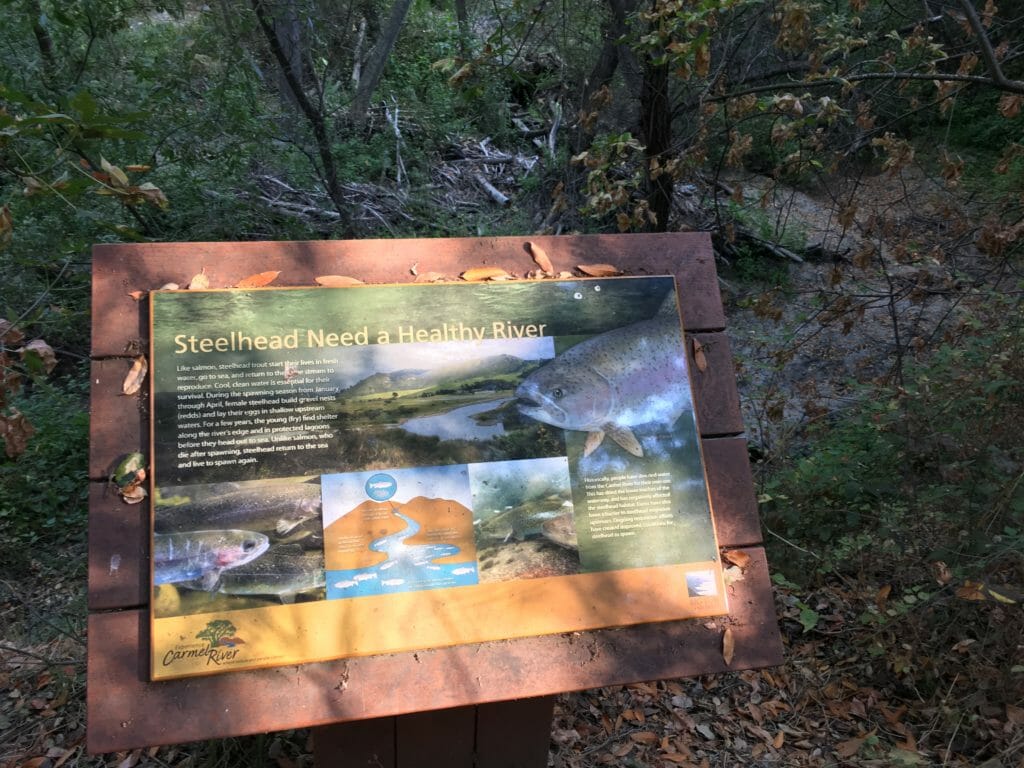

Interpretive sign on the Carmel River, spring 2019.

It was while walking a seasonally-dry side channel of my local stream, the Carmel River, over the weekend that I started thinking about a guy from Michigan named John Rapanos.

You should know this name, because this fellow—unintentionally, no doubt—could really put the hurt on your fishing.

Here’s why. In the 1990s, Mr. Rapanos began filling in three wetland areas on his property in order to develop a shopping center there. Both the state of Michigan and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency warned him this action was not permissible under the federal Clean Water Act.

The landmark 1972 Clean Water Act is one of the most important natural resource laws in American history. It authorizes the government to regulate discharge of any pollutant (including fill materials such as dirt, sand or gravel) into “navigable waters,” which the act defines as “the waters of the United States.” Under current regulations, wetlands are covered by the CWA if they are adjacent to “traditionally navigable waters” or are tributaries to such waters.

Eventually Rapanos ended up in court and, despite losing in both District Court and in the Court of Appeals, refused to take no for an answer. In 2006, he pled his case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

The resulting decision, Rapanos v. United States, is problematic for river systems like the Carmel River and for trout and coldwater conservation more broadly.

There was no majority opinion. Instead, the Court split 4-4-1, with Justice Anthony Kennedy providing a middle ground opinion that was accepted by the conservative faction so the case could be returned to the Court of Appeals for another review based on a different analysis.

The four conservative justices held that “waters of the United States” under the Act are “relatively permanent, standing or flowing bodies of water,” not “occasional,” “intermittent,” or “ephemeral” flows. Furthermore, they argued that a mere “hydrological connection” is not sufficient to qualify a wetland as covered by the CWA—it must have a “continuous surface connection” with a “water of the United States.”

This argument makes little sense to me, on two levels. One, how can you ensure good water quality in navigable waters if you allow pollution in the streams and wetlands that feed into them? Any angling fool can see dumping stuff that would degrade water quality into a tributary that dries back in the summer or into a wetland that is seasonally disconnected from navigable waters will quickly deliver its undesirable payload to proximal navigable water when the rainy season returns.

Second, it seems out of synch with Congressional intent. The legislative history of the Clean Water Act includes this conference language: “[t]he conferees fully intend that the term ‘navigable waters’ be given the broadest possible constitutional interpretation.”

Justice Kennedy’s decision, in contrast, held that wetlands not adjacent to a traditionally navigable water or waters that may not have continuous surface flow could be “jurisdictional” under the CWA if there is a “significant nexus” between them and waters indisputably covered under the Act.

This nexus could be chemical, physical or biological and would qualify wetlands and sometimes-dry waterways for CWA protections if they are “likely to play an important role in the integrity of an aquatic system comprising navigable waters as traditionally understood.”

Under the Kennedy analysis, determining whether a water is covered under the CWA’s water quality protections requires a fact-based inquiry into the relationship of that water to clearly navigable waters nearby. In other words, a scientific assessment.

This does makes sense to me. And while I understand that developers and other interests chafe at the burden imposed on them to certify that proposed projects or operations won’t violate the strictures of the Clean Water Act, clean, drinkable, ecologically productive water, is, well, pretty darn important—for people and salmonids.

I’d like to think that reasonable minds could work out some adjustments to the regulatory side of the Clean Water Act to address concerns of landowners and business interests without pretty much eliminating CWA protections from 60 percent of all stream miles in the United States.

But that’s precisely what the Trump administration is proposing to do with its re-write of the so-called Clean Water Rule. The current administration has thrown out the version of this Rule promulgated in 2015 (based on the Kennedy opinion, and which Trout Unlimited strongly supported) and has revised it to adhere to the conservative plurality opinion in Rapanos.

If you fish, there is no law on the books more important than the Clean Water Act. Trout and salmon, in particular, require clean, cold water to thrive. That’s why Trout Unlimited has been working for years to support the CWA’s water quality protections. Go here to read TU’s comments on the proposed rewrite of the Clean Water Rule.

Sad to say the current administration isn’t stopping there—it’s also trying to reduce the authority states and tribes have under Section 401 of the CWA to review and certify that projects within their borders comply with state water quality standards (here’s an example of how the state of Oregon exercised its 401 authority to protect salmon and steelhead fisheries).

You can help bring some reason to the current headlong push to roll back water quality protections. Go here for more background on the Sec. 401 issue, and you can go here to submit your own comments until October 21.

TU has a lot invested in places like the Carmel River, which is a priority watershed for native steelhead recovery. The Carmel’s wild steelhead run is now a small fraction of its historical average, and while TU-led or supported projects have helped make major gains in restoring habitat and improving fish passage in recent years, we can ill afford activities in the tributaries which compromise water quality in most of the spawning and rearing habitat in this system.

Especially if those activities defy congressional intent and are inconsistent with science-based resource management.