By Jim Wilson

On Oct. 16, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed to repeal the Clean Power Plan, which is designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the electric utility sector. The CPP was originally promulgated in 2015, and was expected to reduce carbon emissions in this country by more than 400,000 tons within 15 years. EPA will accept comment on the proposed repeal of the CPP until Dec. 15, which is why I wanted to get this timely issue in front of you all.

In proposing to repeal a previously issued regulation, EPA argued that the original regulation was issued in a way that is not consistent with the underlying law (the Clean Air Act). The EPA repeal is saying the CPP is likely to cause generation-shifting so is illegal under the section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act, which EPA now says is for setting performance standards that apply to individual sources. The term “generation shifting” is used to mean that utility companies would be expected to comply with the CPP by changing their resource mix among coal-fired units, natural gas-fired units, solar and wind generation.

This differs from a source, or source category-specific emission standard that might be expressed as pounds of emissions per ton of coal or pounds per million BTUs of natural gas burned. The approach that EPA is now suggesting does not make sense to me because an emission limit per ton of coal would either have an uncontrolled rate (which would provide no benefits) or a rate that includes the reductions associated with a carbon capture and storage system, which would be so expensive that coal units would be shutdown.

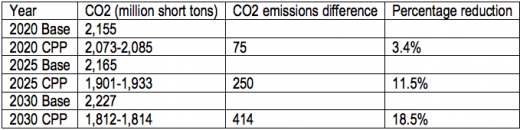

The table below shows the expected CO2 emissions path with and without the CPP (the latter noted as the “base” level). This table shows that without the CPP, electric utility emissions in the United States will likely stay near 2.1 billion tons in 2020-2025, with a slight upward trend approaching 2030. The CPP moves carbon dioxide emissions lower throughout the analysis period, so that Electricity Generating Unit emissions would be 11.5 percent lower by 2025, and 18.5 percent lower by 2030.

Whenever EPA proposes a major rule (which this is), a comprehensive quantitative analysis of the potential effects of the rule must be performed, and is called a Regulatory Impact Analysis.

There are three major differences between the Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) for the CPP repeal and the one performed in 2015 for the original rule. One, the 2017 RIA says that EPA previously (2015) overestimated the value of reducing fine particle precursor air pollutants. EPA’s estimated value of those benefits is now (2017 analysis) lower because they say that many areas no longer have PM concentrations near the levels of the ambient air quality standard. Second, the 2015 RIA cost estimates include significant cost savings associated with demand-side energy efficiency programs, while for the 2017 RIA, these savings are counted as a foregone benefit.

The social cost of carbon estimates used in the 2017 RIA focus on the direct impacts of climate change that are anticipated to occur within U.S. borders, and do not count global benefits. The 2017 RIA’s assessment of the net benefits of repealing the CPP will be about $12 billion in the year 2030. Conversely, the 2015 RIA estimated the 2030 net benefits of implementing it to be $26-45 billion in 2030, with climate benefits being $20 billion by then. So, the difference in the net benefit estimates for the CPP for analyses performed by the same agency two years apart is $38-57 billion. This is an astonishing difference for an agency examining the same program two years apart.

Note that EPA has said that it has not determined whether it will promulgate a rule under section 111(d) to regulate greenhouse gases from existing electricity generating units and, if it does, when it will do so and what form the rule will take. EPA will accept comment on the proposed repeal of the CPP until December 15, 2017. The docket number is EPA-HQ-OAR-2017-0355. Check the EPA website www.epa.gov for instructions about how to submit comments. In my view, this is one of the most important issues in which those of us who care about what climate change means for trout could be involved.

Jim Wilson is the former president of an environmental consulting firm and a TU volunteer from Virginia.