On the California coast between San Francisco and Santa Barbara, a number of streams still have runs of wild steelhead. On a handful of these mostly small drainages, you might get tight to a slabby adult during the winter steelhead season.

And on perhaps three of these streams, you might actually be likely to get a grab from a big fish.

However, should you bring that fish to net, odds are you will find a striped bass giving you the whale-eye rather than a steelhead.

That fact can be attributed largely to the Law of Good Intentions—which as everyone knows almost always has unintended consequences. More on that later.

Of course, the Law of Angler Obsession is equally in play. Fisher-folk will gravitate to whatever water is producing fish. And right now, plenty of anglers in my neighborhood are stripping streamers in coastal estuaries, fantasizing about steelhead but happily settling for the hard pull of Morone saxatilis.

In fact, “settling” really doesn’t do justice to the recent experience of some of my fishing partners—they are landing dozens of stripers per hour, up to 8 pounds in size, on some days.

More than a century ago, commercial angling interests and the fledgling agency that is now California’s Department of Fish and Wildlife decided that striped bass should be imported from the East Coast, where they are native, to the San Francisco Bay, to provide a new fishery.

According to the department’s website, the initial introduction of stripers to California “took place in 1879, when 132 small bass were brought successfully to California by rail from the Navesink River in New Jersey and released near Martinez. There was much concern by the Fish and Game Commission that such a small number of bass might fail to establish the species, so a second introduction of about 300 stripers was made in lower Suisun Bay in 1882.”

The commission need not have fretted. Like steelhead, stripers are opportunistic and took readily to the new habitat—within a few years they were being caught in large numbers in California. Two decades later, the commercial net catch alone was over a million pounds a year. In 1935, however, the state curtailed all commercial fishing for striped bass in the belief that this would enhance the sport fishery.

And probably it did, for several decades anyway. By 1975 the number of adult striped bass in California was considered to be relatively stable at between 1.5 and 2 million fish.

Since then, however, stripers in California have been doing what pretty much every other fish species that favors cold water and has an ocean-going life history has been doing in this state: in most years, showing up in fewer numbers, both in streams and at the end of fishing lines.

A number of scientific studies [Stevens et al. (1985); Delisle et al. (1989)] have examined the causes behind the decline of striped bass populations in California. A primary factor is the amount of water diverted from the greater Bay-Delta (where the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers come together and empty into San Francisco Bay) and related reduced outflows through the Delta.

Coincidentally, that factor is also widely considered to be a major contributor to the declines in once-mighty Central Valley salmon and steelhead runs.

An alternate theory is that striper consumption of juvenile salmon and steelhead in this complex system of waters and wetlands is a more significant factor in the downward trend of Central Valley salmonid populations.

Depending on habitat conditions, stripers probably eat plenty of young fish—like all bass, their rapacious adult selves will swallow pretty much whatever they can cram into their pie-holes, including their own young. But stripers have been residing in the Bay-Delta ecosystem for more than a century and until recent decades Central Valley salmon and steelhead runs remained relatively healthy.

What about in coastal streams where stripers have taken up at least seasonal residence? There has been little analysis of their impact on salmonids in waters beyond the Bay-Delta.

Trout Unlimited and Wild Steelheaders United are working to restore wild steelhead populations south of San Francisco. This work involves a spectrum of strategies and tactics, including helping rural landowners improve the reliability of their water supply so more water can be left instream during the dry season, removing or improving barriers to fish passage, and boosting the science behind steelhead management.

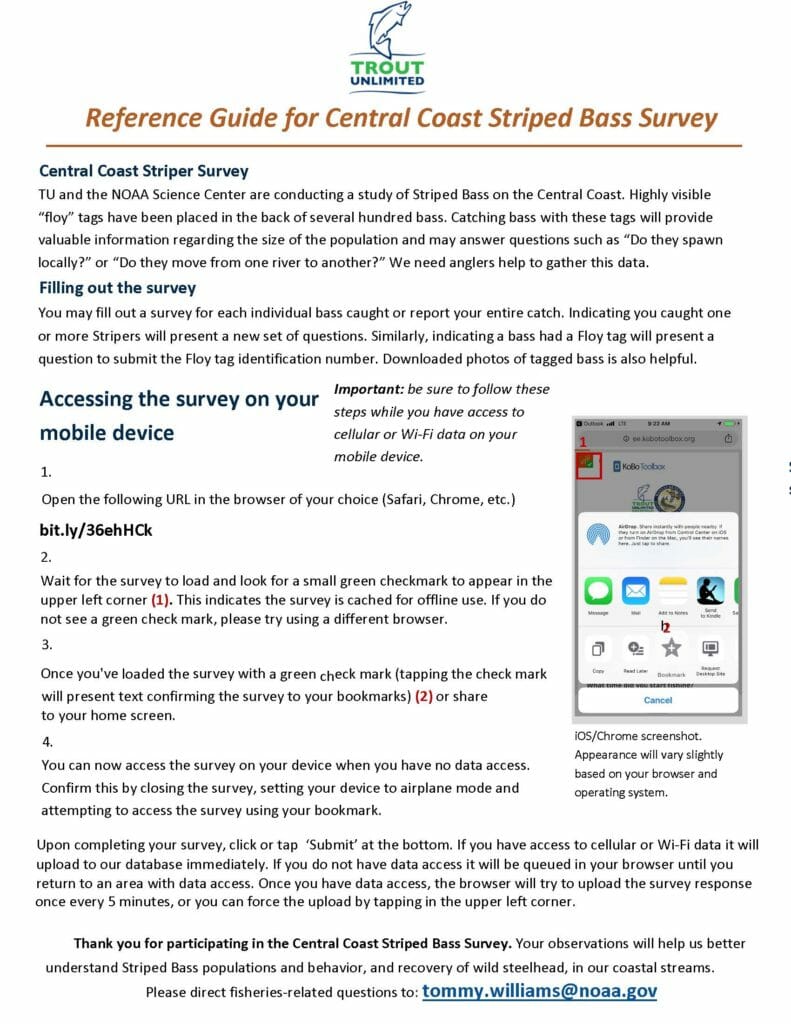

Science is completely dependent on collection and examination of good data. So the Steinbeck Country Chapter of TU and Wild Steelheaders United, led by TU’s Central Coast Steelhead Coordinator Tim Frahm, have begun working with NOAA Fisheries on a novel project aimed at improving our understanding of striped bass population and behavior in coastal streams.

This project involves both tagging stripers, and collecting subsequent catch data from sport anglers via a new app. The project is less than a month old. But anglers have already recorded more than one hundred striped bass landed on the Salinas River or on nearby streams or beaches.

Remarkably enough, none of the stripers caught by anglers thus far have been tagged fish—and some 200 stripers were tagged initially.

In these parts, steelhead usually don’t start coming back into freshwater in numbers until February or March. When they do, perhaps they’ll show up in the angler catch data now being recorded via the new app. In the meantime, local anglers will continue to contribute to the cause of improving coldwater fisheries science—as if they really needed extra incentive.