Anyone who keeps abreast of the Trout Unlimited blog knows that Chris Wood, TU’s chief executive officer and president, has some really good stories and narrative chops.

TU staff who support TU’s habitat, streamflow, and fish passage work in the West got to hear some of those stories on Jan. 28 during Chris’s keynote remarks at a conference hosted by TU’s Western Water and Habitat Program.

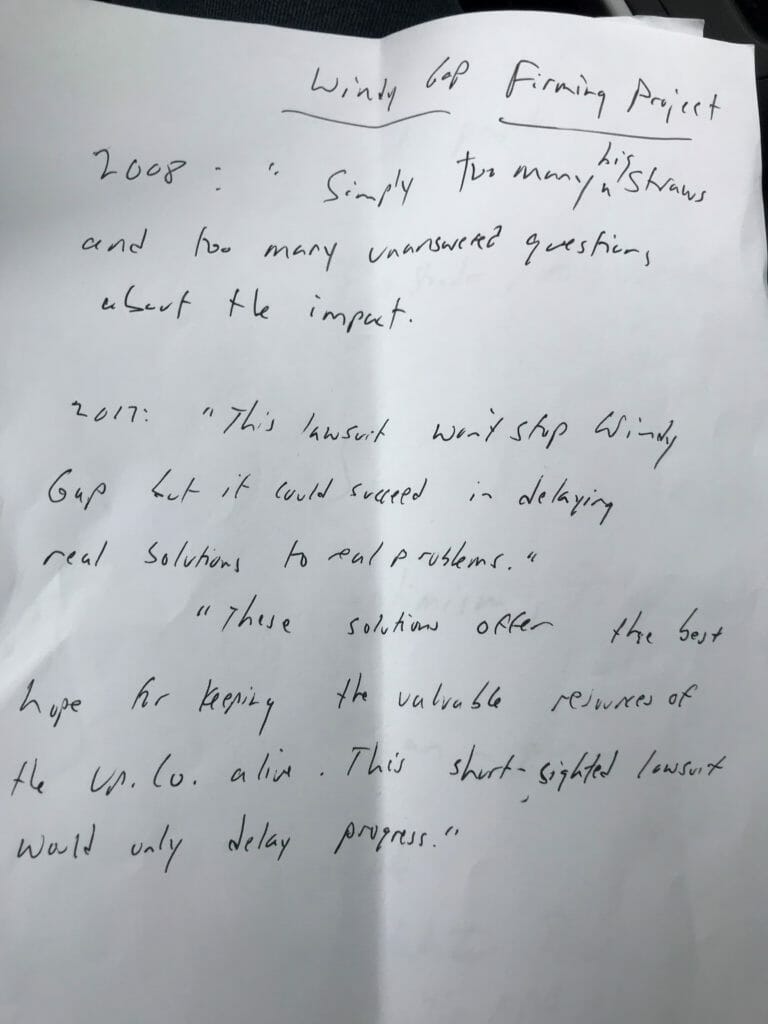

Chris’s remarks were alternately funny, educational, poignant and inspiring. So I did what no career coach would ever advise: I approached Chris and asked for the handwritten, chicken-scratch notecards at which he occasionally glanced during his talk, and for permission to interpret them.

The New Jersey perspective.

Chris Wood, born and raised in New Jersey, got his start in conservation on a salmon river on Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula.

After college, Chris got a call from a college buddy who was working in Alaska, telling him to come visit and fish for salmon. Chris parlayed all his cash reserves into a plane ticket and went. He quickly found himself, his tent, and his buddy’s car submerged by one of Alaska’s notorious high tides as he camped solo on a gravel bar next to a river.

After finding someone to tow him out of the tidal zone, Chris got the car cleaned and dried—and went back to the river to fish. But there he found numerous dead and dying salmon. Being from a highly industrialized area of the country, Chris assumed there had been a train wreck upstream and a load of toxic chemicals had been dumped into the river.

So when he observed another angler casting into the polluted water, he hastened to warn him of the perils of the activity. The fellow shot Chris a knowing look, then gave him a basic primer in salmon biology.

That was same year (1992) a single sockeye salmon (Lonesome Larry) successfully made its way through the Columbia and Snake Rivers systems to reach its spawning ground at Redfish Lake in Idaho. Chris returned to New Jersey and told his parents, “I’m going to save the salmon.”

His father’s response was too colorful to share here.

Sometimes, things start with a box of dead fish.

In September of 2002, between 35,000 and 70,000 Chinook salmon died in the lower Klamath River when federal officials allowed too much water to be diverted in the upper basin (this led to the closure of the Klamath-based commercial salmon fishery three years later). In Washington, TU encouraged the Department of the Interior to advance negotiations between agencies, tribes, irrigators and conservation interests to make sure both fish and people would get enough water in the Klamath.

Someone had shipped a box of dead salmon to TU after the 2002 fish kill so Vice President for Government Affairs Steve Moyer could bring them to meetings to underscore the urgency of the Klamath water situation. On one of Chris’s first days on the job, he was greeted by the spectacle of Moyer scrambling to locate the box before it became too ripe to be utilized for its intended purpose.

Meanwhile, TU’s Klamath lead, Chuck Bonham, told Chris he saw opportunity for a positive, multi-benefit outcome through removal of four old dams below Klamath Lake. This led to TU’s playing a lead role over the past two decades in the campaign to restore the watershed that, historically, has been the third most productive for salmon and steelhead on the West Coast.

A cooperative approach to conservation can deliver good on-the-ground outcomes more rapidly than litigation.

In Colorado, TU grassroots had been working for years to save the South Platte River and its Gold Medal trout fishery from Denver Water’s proposed Two Forks Dam. Thanks in part to this consistent advocacy, EPA administrator Bill Riley killed the project in 1990.

TU’s water work in Colorado only increased in scope and effectiveness after that. And our advocacy on the Two Forks project helped lay the groundwork for a more collaborative approach with water suppliers. This paid benefits on the current Windy Gap Project—TU’s lead role in negotiations on the project helped reduce potential impacts to trout streams and enhance water and habitat conservation measures, to the point where TU now supports it.

Chris recounted that when environmental groups sued in 2017 to stop the project, TU’s Colorado Water Attorney Mely Whiting told the Loveland Reporter-Herald, “This lawsuit likely won’t stop Windy Gap, but it could succeed in delaying real solutions to the problems.”

Coldwater conservation is really about people.

Many of our best remaining native and wild trout streams flow from, or through, roadless areas on our national forests. Chris Wood, then working for the US Forest Service, played a lead role in the development and adoption of the 2001 Roadless Area Conservation Rule.

Surveys showed strong majority support in every Western state—except Idaho—for roadless areas conservation. And after the Roadless Rule was adopted, Idaho petitioned to do their own rule (which TU, through local representative Scott Stouder, helped develop and get adopted). The USFS convened the Roadless Area Rule National Advisory Committee (RACNAC) in 2005 to consider petitions for state-specific rules for management of roadless areas and to help support the Rule’s objectives nationwide.

Chris served on the RACNAC, where five years of meetings led to respectful, even amicable relationships between interests which had historically been at odds. At one meeting, for example, Jim Riley of the Intermountain Forest Products Association gave Wood’s son Casey a toy logging truck, saying, “If your dad won’t teach you to be a real man, I will!”

Chris Wood’s key lessons for conservation success:

(1) It’s about people.

(2) Conservation work requires “relentless optimism, relentlessly applied.”

(3) Focus on the policy itself, not on the people driving or implementing it.

(4) Collaborative stewardship of at-risk resources can really work, but you have to know where your red lines are.

(5) Conservation is a long game.

Editor’s Note: TU is applying these principles now to our highest priority conservation campaign in the Lower 48: removing the four dams on the lower Snake River so we can recover populations of Snake River salmon to a level of abundance that will sustain harvest and local communities dependent on fishing.