By Michael Gibson

Nothing clears the mind like a good chukar hike. So, when the boss called for a work/chukar retreat in lower Snake River Country, I got excited. Late-season chukar in some of the best, and most rugged, chukar country the planet has to offer. About now, you are probably wondering, what’s this got to do with fish?

We’ll get to that.

Our new North Idaho Field Coordinator Eric Crawford was put in charge of food and river transportation. Tom Reed, Northern Rockies Sportsmen’s Conservation Project director, would bring his setters and I would bring my shorthairs. This is big, steep country and we would need all the dog power we could muster.

Two things go through my mind when chasing after these red-legged bandits. First, if you are standing on flat ground, you are doing it wrong. Second, if you are having a pleasant walk, you are not chukar hunting.

The plan was simple, mornings and evenings spent on work planning. Prime daylight hours spent climbing and harassing chukar. We would have three days afield. All told, we covered well over 4,000 vertical feet. And while us bipeds walked eight or so miles a day, my young shorthair Trudy’s GPS collar reported 60 miles by the end of the trip. As is usually the case when chukar hunting, we didn’t get shots at all the birds we saw, but with our crew of four dogs working well together and trying to play the wind, the consensus was that we didn’t walk past any birds within about a half-mile radius of where we travelled. We shot some, we missed some and, at the end of it all, called it a successful hunt.

On one day’s adventure, we happened across an old homestead on the banks of the Snake. A small orchard in the front yard and remnants of tilled grazing pastures were the signs of the self-sufficient cattle ranchers that occupied the dwelling back in the day. Our crew immediately marveled at the hard scrabble lifestyle of these folks.

Saying they were self-reliant would be a gross understatement. In the old days, this would have been at least a full-day horse ride from provisions or medical treatment. Signs of an old ferry service that would take you across to the Washington side were nearby. But the Snake River at this juncture is just as foreboding as the surrounding hills. A massive amount of water rolling through the canyon, as deep as 60 feet in places. Any slip-ups on a ferry would have led to certain doom.

So now for the fish.

Historically, the Snake River watershed was home to some of the largest returns of anadromous fish on the planet. Steelhead, chinook and sockeye all swam through this section of the Snake headed for tributaries in Oregon, Central Idaho and, at one point, all the way into Nevada. Minus fish that peeled off into the Clearwater River, hundreds of thousands of these fish swam past this homestead in any given year. It isn’t hard to imagine that the folks living here supplemented their diet with the tasty flesh of these ocean-going protein packages. At certain times of the year a smoker would certainly need to be deployed to keep up with supply.

Nowadays, this part of the Snake is separated from the ocean by eight federally owned dams, the grand development making Lewiston a seaport and officially making Idaho part of the Inland Northwest. Of course, Idaho’s older tie to the Northwest is stocks of salmon and steelhead that have the longest and highest migration of anadromous fish in the world.

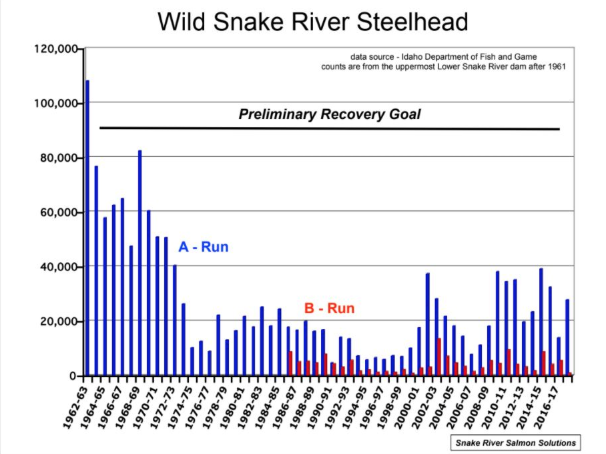

But these fish are struggling. Populations in recent years have plummeted. A combination of fish passage, poor ocean conditions, predation and climate change are causing runs of wild salmon and steelhead to be counted in the thousands, not hundreds of thousands. Solutions to the problem are complex. A combination of spill, predator control and hatchery supplementation are a near-term band aid that only seem to stave off extinction. To see real recovery, like the number set by regional agencies and partners, all stakeholders need to sharpen their pencils and find long-term solutions. A free-flowing Snake River could certainly help. But these solutions will only be realized if they work for people.

Trout Unlimited stands ready to help solve this complex challenge. We spent a lot of time talking about this in between chukar walks.

In years past, when fish runs were better, we would have fished as much as hunted. Instead we spent only an hour back trolling after running upstream in Crawford’s boat to cover some fresh chukar ground. We weren’t able to hook into any fish. Steelhead are notoriously finicky, and when numbers are suppressed as they are now, catch rates go down even further.

We’ll be back though. The siren song of chukar is too much to resist. Maybe next time, it will be worth spending more time on the water. We can only hope.

Michael Gibson is the Idaho Field Coordinator for Trout Unlimited’s Sportsmen’s Conservation Project. He lives in Boise, Idaho.