Few people know rivers more intimately than anglers. Every bend, pool and overhanging trees of our favorite river stretches are stored in the recesses of our brains. Particularly those where big fish are known to hide.

From year to year, the pools we fish are usually static and don’t change dramatically. We walk up to our favorite stream and, by all appearances, the water looks the same. Things we have a hard time observing happen throughout the year.

Fish we catch in a specific pool during the summer are likely different than the fish in that same pool during the fall. Why? Because fish, especially native trout, are constantly on the move throughout our river systems.

Trout movement is not only fascinating, but it is critical to the long-term resilience of many native fisheries. Fish in stream environments move for a wide variety of reasons. We are broadly familiar with the plight of the salmon, hatching in freshwater, moving downstream as smolts and, entering the ocean. Their magnificent return to the rivers during spawning migrations, hundreds of miles up the Columbia and Salmon rivers, illustrates fish movements at a grand scale.

Few people know the same phenomenon occurs with inland native trout such as the cutthroats. Some well-known cutthroat trout migrations include Yellowstone cutthroat trout from Yellowstone Lake migrating up the Yellowstone River and into Thorofare Creek, and the Bear Lake (Bonneville) cutthroat trout spawning migrations up St. Charles and Swan Creek in Idaho and Utah.

Some of the ground-breaking research on movements of riverine cutthroat trout was completed by Russ Thurow with Idaho Fish and Game in Idaho’s upper Blackfoot River in the 1980s. Then, in the late 1990s, Trout Unlimited’s own Warren Colyer identified major movements of Bonneville cutthroat trout in the Thomas Fork of the Bear River in Idaho moving more than 50 miles through the Bear River and into a separate tributary in Wyoming to spawn.

Less charismatic are the seasonal and spawning movements of river/creek dwelling cutthroat trout. In Utah’s Weber River, migratory cutthroat trout fell under the radar for decades until around 2009, when through normal sampling, the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (UDWR) observed a small number of cutthroat trout in the Weber River — a river renown as an exotic brown trout fishery. TU staff had the opportunity to participate in subsequent research completed by Utah State University and the UDWR investigating the life cycle of these cutthroat trout and, to everybody’s surprise, these fish were making spawning migrations into small tributary streams, not larger than three feet wide, that flow directly into the Weber.

Anecdotally, we observed these cutthroat trout migrations were blocked by several road crossings, low-head dams and other channel spanning structures both in the Weber River and the tributaries. These human-made structures blocked most of the spawning habitat from the cutthroat population in the mainstem.

Breaking down known barriers

TU initially worked with our partners such as the UDWR, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and others to develop individual projects to modify these road crossings and re-establish fish passage. This included installing the Strawberry Creek fish ladder, reconstructing a driveway approach on Gordon Creek, and modifying culverts on Jacobs Creek. Plus we also constructed a fishway and fish ladder on the irrigation diversion at the mouth of Weber Canyon, and completely removed a channel-spanning irrigation diversion in Morgan Valley.

These have been rewarding projects for all those involved, but TU and our partners still lacked the big picture perspective that we needed to take a more strategic approach. We knew there were other barriers to upstream fish movement we had not identified. Thankfully, as part of a broader planning effort within the Weber River basin, we had the opportunity to take a step back and assess the entire river basin for barriers to fish movements.

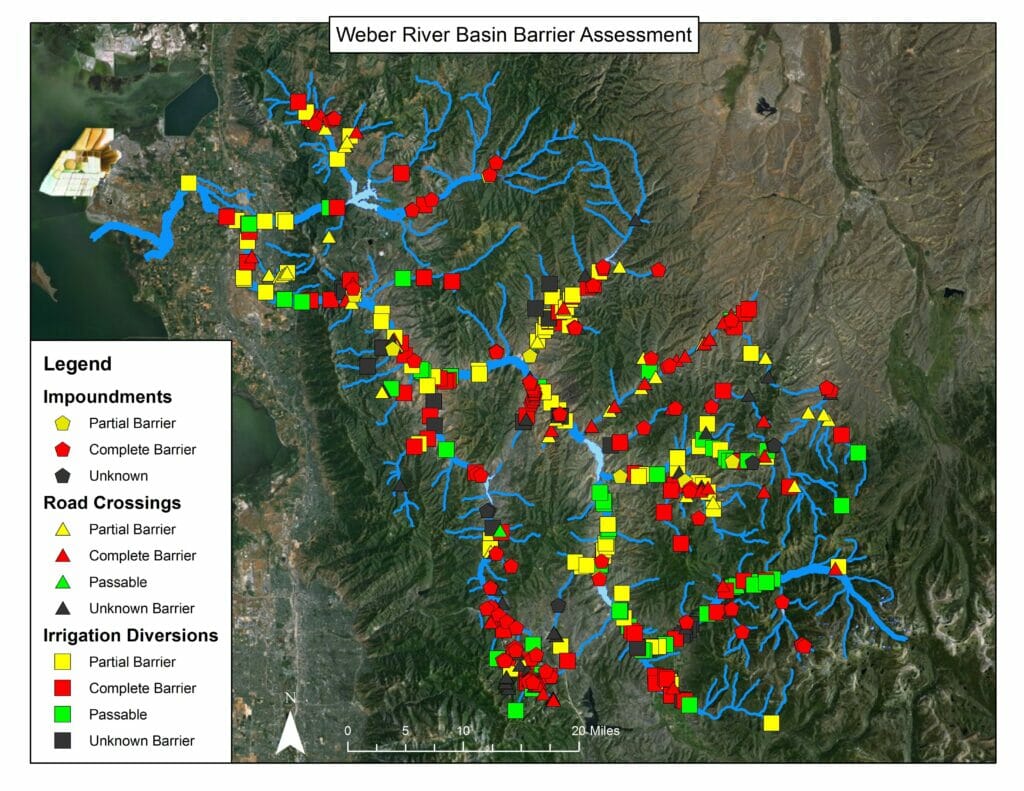

Mapping barriers in the Weber

For this assessment, we determined we needed to take a systematic and consistent approach to assess barriers on both the Weber and Ogden rivers, and their tributaries. It is impractical to drive to or walk to every structure in the basin due its large size. There are 129 miles of main river channel (including the Weber and Ogden rivers) and 934 miles of tributaries such as Chalk Creek, Echo Creek and East Canyon Creek, as well as other headwaters. Access was also an issue since much of the basin is on private land. Securing access to every site would have been difficult.

We developed a strategy to assess barriers by using the rich sets of open source aerial imagery. It just required hours and hours of screen time. We systematically panned through the entire Weber River Basin starting at the point where the Weber River enters Great Salt Lake and moved upstream into every tributary. We used other mapping data sources such as road networks and statewide water rights information to help identify where human infrastructure was interfacing with the river.

We classified the infrastructure into three categories:

- Road crossings. These came in two forms. Bridges and road culverts or pipes. Road culverts, are by far the most common barriers. Most culverts are composed of corrugated metal pipes. In typical configurations culverts are set too steep, or narrow the stream width causing water velocities to accelerate through the pipe, preventing upstream fish movement. These can be seasonal or complete barriers depending on the slope of the pipe, and how the outlet is configured. Culverts steeper than about 3 percent and with vertical drops at the outlets are usually complete barriers. If the slope is less than 3 percent and there is no drop, trout are usually capable of bursting through culverts during low to moderate flows.

- Irrigation diversions. These are typically instream structures that allow water rights holders to take water out of the stream for consumptive uses such as irrigation. Although necessary for water rights holders to divert water, they can have consequences on our fisheries. If they are large dams, or channel spanning structures they are likely to block upstream fish movements, especially if they are concrete structures, or have some sort of apron that the water flows over. In addition, the headgates —the points at which water rights holders take water out of streams — pose threats to fish moving downstream. Fish are frequently entrained into irrigation systems, which is typically a one-way trip to death. Migratory fish are at even greater risk of entrainment because they interface with a more diversions as they move up and downstream.

- Impoundments/dams. These were miscellaneous structures throughout the basin, including large dams, flow gages, and on-channel ponds. Because these structures typically impounded water, most of them were barriers to upstream movement.

We used definable characteristics from the aerial imagery to aid us in determining if the infrastructure was a barrier to fish movement. Characteristics such as turbulent water at the outlet, a perched culvert (a culvert with a waterfall at the downstream end), ponded water, dam boards, water flowing across a skirt or apron, and culvert length informed our determination.

We used those characteristics to color code every barrier as passable (green), a partial barrier (yellow), a complete barrier (red), or further assessment needed (dark gray).

We also quantified the number and location of irrigation diversions, which help us determine the feasibility of building fish screens at the headgates within certain areas of the Weber River Basin with high numbers of cutthroat trout.

The results of the barrier assessment were sobering. We assessed 419 total structures and 196 of them were complete barriers and another 125 were partial barriers. Barriers were in the form of road culverts, concrete irrigation diversions, rock dams, you name it.

It is even more astonishing to consider the cost of modernizing the structures to make them passable to fish. For example, an average culvert replacement costs approximately $60,000 when engineering is factored into the equation. For irrigation diversion structures, the average cost of fish passage is $20,000 per vertical foot that we hope to achieve passage. So, a person could expect to pay $80,000 to replace an irrigation diversion with a 4-foot drop. Or if we want to screen a diversion, we can expect to pay $6,000 per cfs of flow.

| Impoundments | Water Diversions | Road Crossings | Total | |

| Partial | 10 | 81 | 34 | 125 |

| Complete | 81 | 70 | 45 | 196 |

| No Barrier | 52 | 1 | 53 | |

| Needs Evaluation | 6 | 20 | 19 | 45 |

| Total | 97 | 223 | 99 | 419 |

This effort revealed that habitat fragmentation is a huge issue in the Weber drainage. Coupling the threat of extensive water development and habitat loss due to highway construction and flood control, the barrier assessment is one more piece of the puzzle of data that shows how threatened the Weber River is.

This brings up the question of addressing the barriers. Science has established that fisheries in rivers where numerous barrier fragment habitat are not as healthy and resilient as interconnected systems where fish can move freely throughout the river network. We cannot work everywhere, so we need to prioritize. In the Weber River, we have prioritized our habitat reconnection efforts in two areas, the lower Weber River and tributaries from Morgan downstream to Ogden and a major tributary called Chalk Creek. We have prioritized these areas due to the presence of cutthroat trout and the migratory nature of these fish. Many great projects in our Weber River program have come from this assessment.

Broadening the effort

If we expand what we found to other river basins in the state, it is plausible to visualize thousands of these barriers across the landscape. The value of this barrier assessment to the partnership in the Weber River has motivated other partners to consider similar efforts in other river basins, and even statewide in Utah. The Utah Migration Initiative, through the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, undertook a statewide effort to develop a smart phone mobile app that biologists and partners like TU staff can use to begin mapping all of the barriers in the state. All that data will be stored on an online map. This broadly-accessible data will allow partners to work collaboratively at watershed scales to remove the most important barriers to fish movement and improve our fisheries in the state.

We are encouraged to see a cohesive statewide effort to improve our understanding of barriers and how they affect our fisheries. This is one more example of TU’s science innovating our collective approach to understanding threats to our fisheries, and developing strategies to improve them.

Paul Burnett is the Utah Water and Habitat Program Director. His focus is on the Weber River Basin.