Pebble mine is on the ropes in Alaska, but the work goes on to protect Bristol Bay once and for all

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “finds that the project, as currently proposed, cannot be permitted under section 404 of the Clean Water Act.”

With those words earlier this week, the prospects for the development of Pebble mine suffered a mighty blow. The prospects of the mine are severely diminished, but until we permanently protect the area, the threat remains.

Fifteen years ago, I remember being on the phone, and distracted, as someone first warned me about the imminent threat of a new mine in southwest Alaska. My first thought was, “Pebbles? Are we really mining pebbles now?”

Pebble is a proposed massive gold, copper and molybdenum mine in the headwaters of Bristol Bay, Alaska. If built, the mine would sit astride two river systems—the Kvichak and the Nushagak. Its construction would require the industrialization of a pristine area, home to the Yup’ik, Dena’ina, and Alutiiq peoples who have lived in the area for time immemorial. It would require an earthen dam several miles long to hold back its toxic tailings—in perpetuity. The finishing touch on this mother-of-all-bad-ideas is that the area is prone to a lot of earthquakes.

Every year the Kvichak system produces nearly half of all the wild sockeye salmon in the world. The Nushagak is among the world’s top producers of Chinook salmon. The bounty of these two river systems help to explain why the commercial fishery in Bristol Bay is worth $1.5 billion annually and provides over 14,000 jobs. It also helps to explain why the Alaska Native villages across most of the region—that have depended on the salmon runs for millennia—are so opposed to the mine.

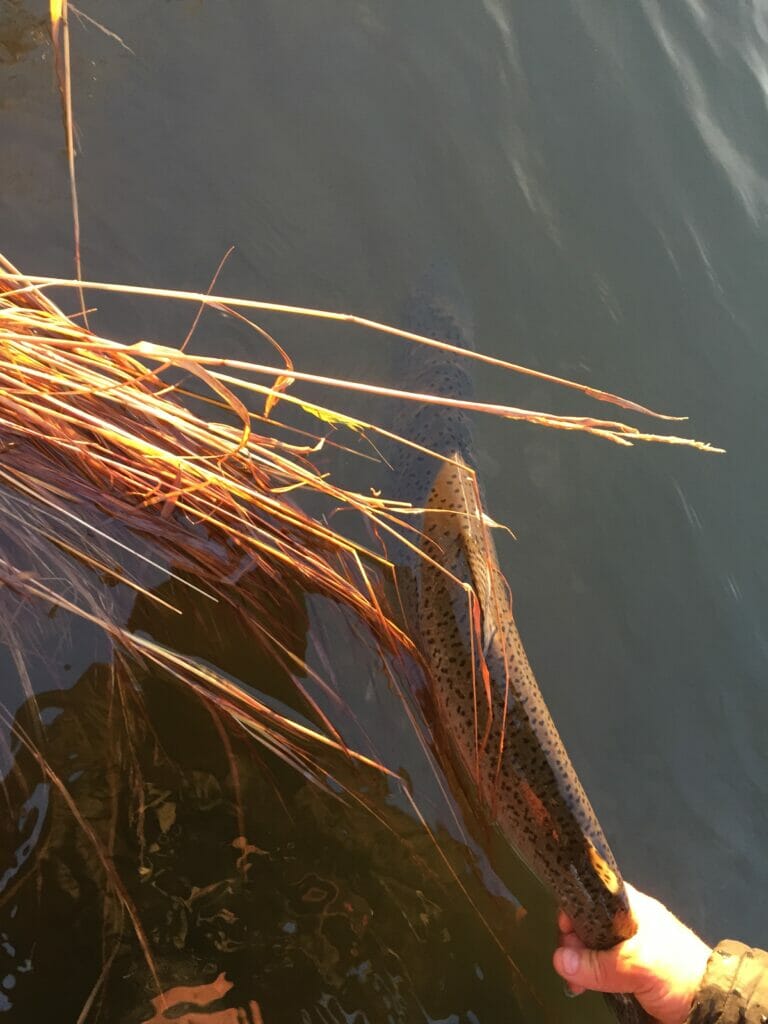

It is the native rainbow trout, which move from Lake Iliamna to follow the salmon, that make Bristol Bay a bucket-list destination for sportswomen and men. Fifteen years ago, Brian Kraft, the owner of the Alaska Sportsman’s Lodge, described the threats of the mine, as we stood waist-deep dead-drifting flesh flies on the Kvichak in front of his lodge.

As my fly line drifted in front of me, I lifted it to re-cast, and felt a strike. “There he is!” I said excitedly.

Suddenly, 35 yards to my right, a fish burst out of the water. I turned to Brian. “Did you see that fish rise?”

He laughed. “That’s your fish!”

Such is the strength and power of the magnificent rainbows of the Kvichak.

Brian was the reason that Trout Unlimited first got involved in the fight to protect Bristol Bay. To be certain, other lodges such as Crystal Creek, Bear Trail, Royal Coachman, No See Um and many others have all been hugely important, but Brian was the first to see and act on the potentially devastating downstream consequences to the villages and the world’s finest salmon fishery.

Much of the conservation in the state of Alaska was forced onto it by the lower 48 states. From the start, TU took a different tact. Stopping Pebble was a fight that had to be won in Alaska by Alaskans.

Over the years, we hired guides, commercial fishers, residents, scientists, former state elected leaders, and stood behind the businesses and communities who would be most impacted if Pebble was developed. The strength of TU was evident in our ability to bring local, statewide and national attention to the peril of the Pebble mine. The proof of success is evident in the fact that nearly 85 percent of the people from the Bristol Bay region oppose the Pebble mine; statewide, almost 65 percent oppose the mine.

Over the past few years, Nelli Williams, and her relentless team of advocates working in Alaska and D.C., worked hard to engage the Trump Administration in a positive and constructive manner. Their point is TU’s point: Republicans and Democrats both love to fish. Both should care about conservation.

Outdoor retailers were hugely important in the fight, especially Orvis, which once again showed that there are many who talk about conservation, but only a few that walk the talk. Every conversation, every “no Pebble” sticker, every donation—no matter how small, like a brick in the wall—made the case. Bristol Bay is the wrong place for a massive industrial scale mine.

Anglers and hunters are slow to engage in politics, but they understand the threats to healthy habitats better than most. This was evident when we delivered a letter to the White House signed by nearly 50,000 anglers and hunters, and another signed by over 250 outdoor businesses asking the President to stop the Pebble mine and protect Bristol Bay. Simon Perkins, the new president of Orvis, was among those who came back to D.C. to voice concerns about this project.

One year ago, we had a memorable dinner at my house to celebrate the 19th birthday of Triston Chaney. Triston is a commercial fisherman from Dillingham, Alaska, who was in D.C. to visit decision makers with John Holman of the No See Um Lodge, Orvis and Taj and Rocky from Grizzly Skins of Alaska Lodge. Triston, John, and I spent a few hours the next morning fishing for D.C.’s answer to those Alaskan rainbows—carp.

More recently, we were helped when high-profile former Trump officials and the President’s own son weighed in against the Pebble mine. Johnny Morris, owner of Bass Pro Shops, appeared on the Tucker Carlson show, and both host and guest were awesome advocates for protecting Bristol Bay.

Conservation is a non-partisan game, and it is our job as advocates to make a compelling case to whomever is in office for protection and restoration of our lands and waters. Across the nation, Trout Unlimited brings grassroots organizing, durable partnerships, science-backed policy muscle, and legal firepower on behalf of trout and salmon fisheries, healthy waters and vibrant communities.

In Bristol Bay, we stayed the course. Thanks to President Trump and his team for listening.

The Army Corps of Engineers and the Trump administration dealt a harsh blow to the prospects of the Pebble mine. But greed is a forceful motivator, and Pebble will likely be back. We cannot let up our efforts in Bristol Bay until Pebble’s permit is officially denied and the state-owned land underneath which the mineral deposit lies are permanently protected from short-sighted projects such as the Pebble Mine.

President Theodore Roosevelt’s words about the Grand Canyon are as applicable today to Bristol Bay.

“Leave it as it is,” he said. “You cannot improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it.”