I recently had a video call with a Trout Unlimited volunteer in New York. I couldn’t help being distracted. Over his shoulder I could see a stream in the background.

“What river is that?” I asked.

“The West Branch of the Delaware,” he replied. “I actually was watching fish rise before this call started.”

Oh, the envy.

How nice to be able to check river conditions by looking out your kitchen window. Most of us aren’t quite as fortunate.

When I’m considering a fishing outing, my first step is to pull up USGS streamflow data to make sure the water level is OK.

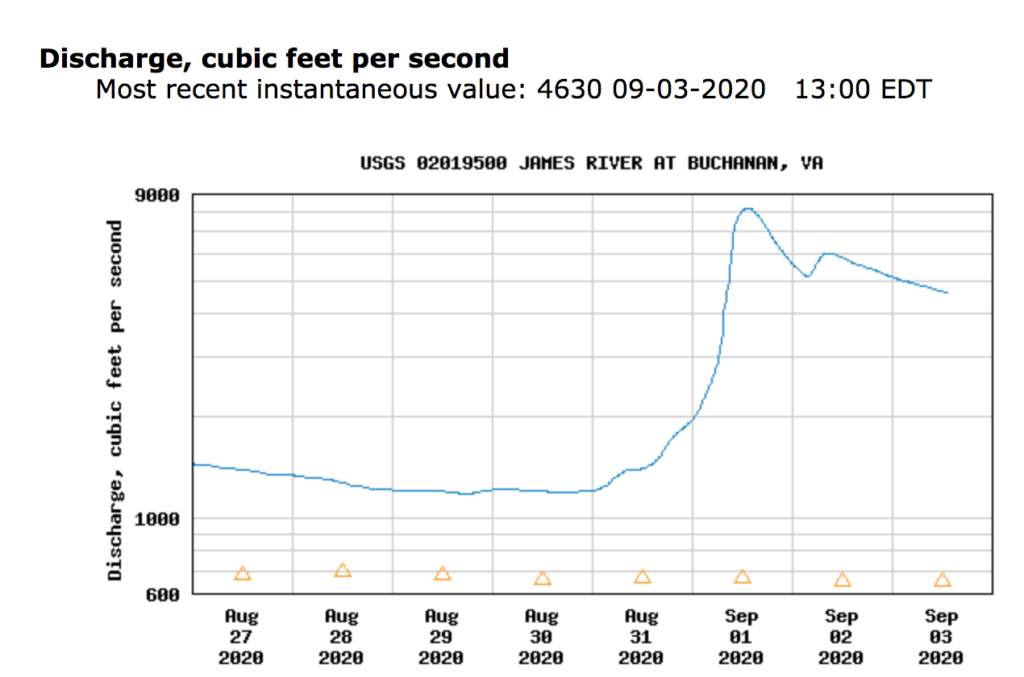

The other afternoon I was in the mood to throw poppers for James River smallmouths. We’d had some rain in Western Virginia the day prior so I pulled up the USGS site.

I was surprised to see that the James, formed by the Jackson and Cowpasture rivers, was more than 10 times higher than its normal level for this time of year. A little more digging into other streams in the area confirmed that the upper James watershed had gotten hammered by rain.

Tailwaters can be a good option when other rivers are up but the Jackson tailwater — about an hour north of me — was blown since releases had been increased in the wake of the previous day’s rains.

The Smith River tailwater, about an hour south, was the other option. I was relieved to see that release levels had been steady for days.

But when I arrived, my heart sank. The river was brown.

And not tea-with-milk brown. Thick-coffee-with-heavy-cream brown.

Streamflow is only part of the picture. Especially in the summertime, isolated thunderstorms can hit little tributaries, and those little tribs can muddy up larger streams in a hurry. (These sediment load issues are among the reasons TU puts so much effort into restoration work on smaller streams with erosion issues.)

In the case of the Smith, there’s one particularly problematic tributary that runs through farmland and has terrible erosion issues. I figured that was the issue the other day so I went upstream. The water color was only slightly better.

Apparently the reservoir above is stained, possibly due to regular heavy rains in the upper watershed this summer.

After driving for an hour what was I going to do? Fish, of course.

I’ve found that fishing in latte-colored water is pretty much a fool’s errand, unless catfish are the quarry. But if there is even a smidge of visibility — that tea-with-milk color — I’ve caught trout and steelhead.

I could see the tops of rocks under the surface, so figured visibility was about a foot, maybe 18 inches. The water was too turbid for safe wading, even near shore, so I had to bail on fly fishing and grab the spinning gear.

I hadn’t lost all hope. One of my better Smith River browns came from similarly dirty water, so I tried to be optimistic.

That optimism was misguided. Two hours of effort with a variety of “noisy” lures such as spinners and plugs with rattles proved fruitless. To add injury to insult, some critter stung me on the ankle, just above my boots, as I scrambled around the brushy banks.

Sometimes you get a signal that tells you that enough is enough.

Technology has made trip-planning more efficient in recent years and that technology is getting even better. For example, at TU we are starting to deploy inexpensive Mayfly stream monitoring stations to shore up the amount of data available to the public.

It should just keep improving. These days there are live surf cams up and down our coasts. Could live river cams eventually become similarly ubiquitous? Maybe.

Even if it comes to that, unless we live streamside, surprises when we get to the water will continue to be part of fishing. But we have to remember that there can be good surprises, too. Great hatches. Better-than-expected water conditions. Lighter-than-expected crowds.

We just have to hope the good surprises outnumber the bad ones.

Mark Taylor is Trout Unlimited’s eastern communications director, based in Roanoke, Va. Although he’s an obsessed trout and steelhead angler, he’s had plenty of fun soaking stinkbait and worms for catfish in muddy water.