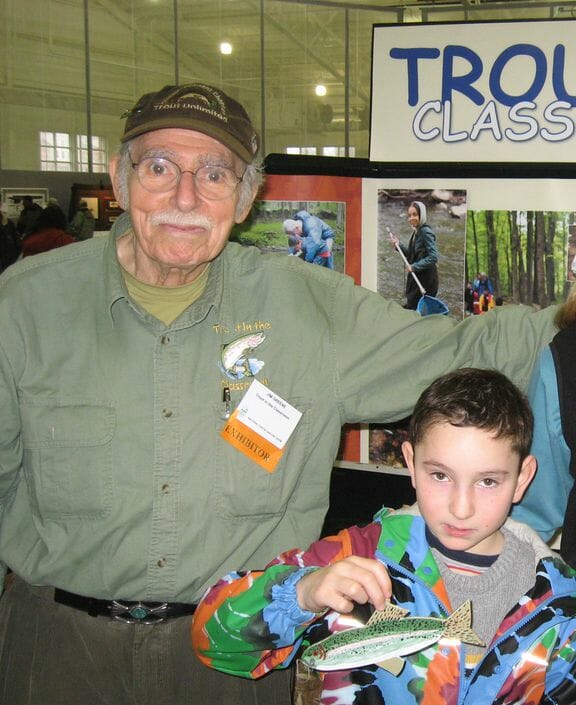

I first met Jim Greene as a relatively new employee of Trout Unlimited. He was an incredibly energetic earnest, and gregarious man. We went to lunch and I listened to how he and others—Jim would always insist on crediting others—helped to grow the Trout in the Classroom program in Maryland from a handful of schools to a hundred.

Jim’s passion for training the next generation off conservationists was summarized in a speech he gave to a group of Trout in the Classroom teachers and volunteers:

“The future of our water and natural resources will depend on the ability and willingness of tomorrow’s adults to demand and support policies and actions to maintain and restore health to environmentally threatened or damaged areas.”

Jim passed away recently from complications associated with COVID-19. He leaves behind his family and his beloved spouse, Ros.

He was unassuming, gentle and unfailingly kind. He epitomized the best of Trout Unlimited volunteers.

Jim was the president and CEO of Waterwisp flies, a position he held for more than 20 years. Waterwisp’s innovation was to tie dry fly’s upside down and backwards, so the fish below did not see a hook profile. Before that, Jim was an advisor at the World Bank, and a U.S. Foreign Services officer serving abroad in countries such as Kenya and Tanzania. He was unassuming, gentle and unfailingly kind. He epitomized the best of Trout Unlimited volunteers.

Jim won the Ray Mortenson award in Scranton, Pa., in 2015. The Mortenson is the highest annual award Trout Unlimited gives a volunteer.

In order to get Jim and Ros to the annual meeting where he would receive the award, I made up a story about wanting to personally honor Jim for his Trout in the Classroom work and convinced them to drive to Scranton. They came, even though the meeting interrupted the Jewish high holy days. After he learned in the presence of hundreds of other people that he was receiving the Mortensen award, his response was, “No. You should not have done this. There are too many more deserving people than I.”

Last year, Jim attended a holiday party at our home, and I had the privilege of introducing Jim to Mason and Palmer Kasprowicz, the two intrepid teens who formed Flies by Two Brothers. Mason and Palmer are two great young men whose fly-tying business helps pay for their college tuitions. Jim huddled up with them for at least an hour. Who knows the wisdom he passed down? No one, however, was surprised he spent the time.

When my oldest son, Wylie, was in grade school, my family sponsored a Trout in the Classroom tank at his public school in Washington, D.C. Jim insisted on meeting with Wylie’s teacher and walking through the curriculum to ensure that she was serious and committed. Afterward, I asked myself, “Does he really do this at every one of his schools?” He did.

The spring before last, Jim and I made plans to fish the shad run on the Potomac River from Fletchers boathouse in Washington, D.C.

When we arrived, grey sheets of rain dropped from the sky. The Potomac had that almost oily look that rivers and oceans get during serious rainfalls.

I looked at Jim, and said, “How about breakfast?” Over breakfast, and only after much prodding, I learned Jim was an outstanding college athlete and was later friends with the inimitable Pete Seeger—even helping him to build his home in New York. Walt Gasson, who leads our TU Business program, and who was also friends with Jim said, “Like Pete, Jim lived a long time and never gave up hope in a better day.”

In the intervening months after the rainout at Fletchers, we made several plans to get together which Jim had to cancel because of his near constant care for Ros. I called Ros yesterday and asked if there was anything that I could do to help. It is the kind of question people always ask situations like this, and I appreciated her honest response. “No. There is only one thing I want, and he is gone.”

Jim would not be happy about me writing this about him. Moments before accepting the Mortenson award he whispered to me, “Please, Chris. Shine the light on someone who deserves it more than I.”

Hey, Jim, the light that you for so long held on others, now belongs to you.