Mayflies. We all love them. We all fish them. But do we understand them?

Orvis’ Tom Rosenbauer, in association with the folks at The New Fly Fisher, notes that entomology has probably discouraged more would-be fly fishers from diving into the sport than we might ever know. But, he also says, it doesn’t take a biologist’s understanding of aquatic insects to be able to determine what trout are eating, and what flies we might use to imitate that food.

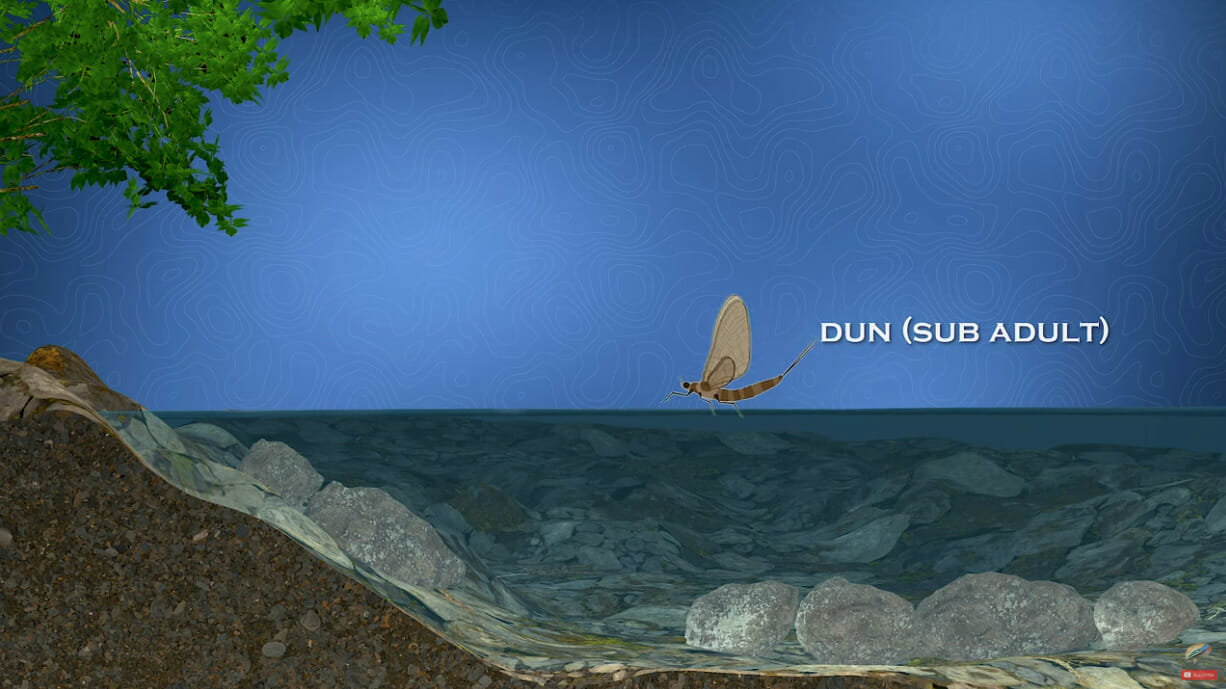

And mayflies are one of the four main aquatic insects that are vital to trout (stoneflies, caddis and midges round out the group). Mayflies, Rosenbauer explains in the short video above, spend the first year of their lives as nymphs, existing below the surface where they provide a dependable source of protein for trout. Eventually, the nymphs “emerge” into a dun, or a sub-adult mayfly. At this stage, the bugs fly into nearby streamside vegetation, where they complete the molting process and become the adult mayfly, which is called a spinner.

When you see mayflies dancing over the water — and, if you’re lucky, trout rising to them — you’re seeing what’s known as a spinner fall. This is when the adult mayflies are laying eggs in the water. Over the course of their egg-laying, they’ll “fall” to the surface a final time and eventually die. You may also see fish working as the nymphs emerge and transform into duns. These are the two most-obvious times to see trout going after mayflies (although they eat mayfly nymphs all year long).

Common mayflies anglers will encounter on trout streams include blue-winged olives, green drakes, March browns, sulphurs and pale morning duns. The giant hexagenia limbata, or simply the “hex” that sometimes turns up in lakes and slow-moving rivers, is the biggest mayfly in North America, and the BWO is likely among the smallest.

Regardless, understanding the life cycle of mayflies doesn’t require a biology degree, and the more you know about these amazing insects, the more trout you’ll catch.