“You committed to driving to Maryland tomorrow for a Trout in the Classroom release.” My colleague’s words were not music to my ears.

I had completely forgotten, and wasn’t really thrilled about the outing. I drove the few hours to the Lucy School in Middletown, Md., with relatively low expectations. If you have seen one Trout in the Classroom release, and I have seen a few, you have seen them all, right?

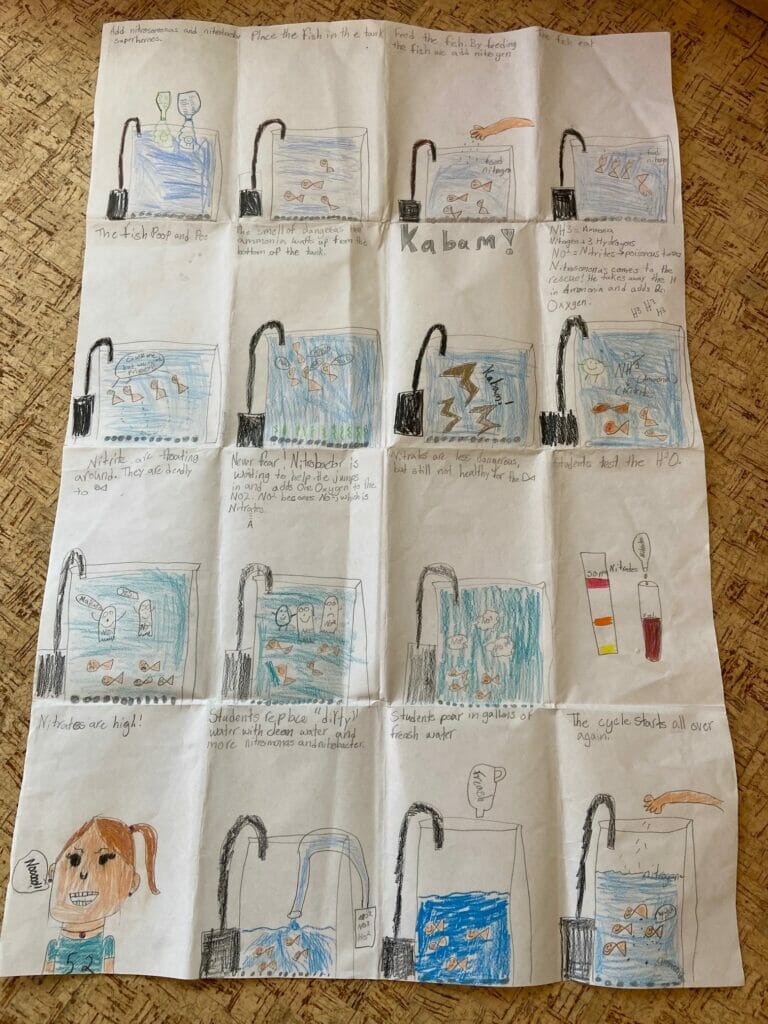

By way of background, TIC is a program where volunteers work with the state and local schools to secure trout eggs, raise them in a tank, learn about water quality, ecology and the hydrologic cycle, art and science, and then release the baby trout into nearby rivers—all with the blessing of the state natural resource agencies.

I did not want to make the drive. In part because I have had my own reservations about Trout in the Classroom. The program itself is phenomenal. I have watched in wonder as Lilli Genovesi, Trout Unlimited’s New York City TIC coordinator, worked with kindergarten kids and their parents and then pivoted to high school kids who had, let’s just say, very short attention spans. Through it all she kept everyone from age 5 to 17 engaged, if not enthralled.

My issue with TIC is that the program may inadvertently teach kids that it is OK to release non-native trout (typically rainbows) into waters they do not belong. Non-native trout pose a profound threat to many native trout populations in the United States. Other states such as Wyoming, helped to create alternative programs such as Adopt a Trout, which uses technology such as telemetry to help school children track the movements of native cutthroat through Wyoming’s rivers. That data then informs state, federal, and TU restoration priorities.

Also, high school teacher, Dr. Kirk Smith in Virginia, created Trout Out of the Classroom, a program where high school students provide data and research to the state to inform where native brook trout should be reintroduced. These programs are more in tune with TU’s mission than releasing a bunch of rainbow trout into waters where they are not native.

Cut back to Friday morning… I pulled into the lot of the Lucy School in Frederick, and was met immediately by Chuck Dinkel. Chuck is a friend of Jim Greene, a man I loved, who passed from COVID last year. Jim introduced Chuck to Maryland’s TIC program, and they and other volunteers expanded the program from a handful of schools to more than a hundred.

Chuck met me as I got out of the car.

“Come on, let’s go see the kids.”

As we walked into the classroom, Sandy, the energetic fourth-grade teacher, introduced me to her kids. The Lucy School is remarkable. Learning about nature and conservation is an important part of the curriculum. The kids’ conversation turned to snakes, including one that sunned itself on the pavement outside the door they used for recess. I shared with them how a black snake once cleaned out all the mice at our home in West Virginia before I moved him back outside.

Chuck tossed a brood X cicada—which are in full swing after their 17-year hiatus—into the class’ trout tank of fingerlings, and we watched the smaller fish peck at it, but not eat. One of the kids said, “The fish need smaller inverts.”

I looked at Chuck. Inverts?

“Invertebrates,” he said. “Trout sushi!”

Sandy showed the kids a series of flash cards. “What’s this?” Water penny! Stonefly! Mayfly! The kids excitedly shouted the answers.

Chuck pulled out a small vial with a large bug in a liquid solution, and asked the kids to identify it. I feared someone would ask me. After some consultation, the kids said, “It is a crane fly.” Chuck nodded his approval.

I drove to the creek where the Department of Natural Resources said the kids could release their trout, taking work phone calls along the way.

“Are the presentations for the board meeting ready?”

“May Tammy go on sabbatical?”

“Do we have enough funding to hire this new position?”

I arrived at Little Catoctin Creek ready to leave.

That changed as I watched the smiles, silent prayers, and quiet tears as the fourth-graders released the trout they had raised since December into the Little Catoctin under Chuck and Sandy’s careful supervision. After the release, the kids all gathered into a circle and conducted PH, nitrite, nitrate, and ammonia samplings of the creek.

Chuck asked, “What’s upstream that may influence nitrate or nitrite levels in the creek?”

The kids responded, farms and cows. “Better to keep the cows out of the stream,” one Fourth-grader said. The kids then discussed the implications of their tests.

“What keeps the pollution from entering the river here?” Sandy asked the kids. All the kid’s raised their hands. Sandy pointed to one who said, “Riparian areas that buffer the stream from pollutants.”

I looked at some of the other parents standing outside the circle, and heard one ask, “Riparian area? Where did they learn that?”

I’d warrant that 95 percent of Americans have no idea how important riparian areas—the streamside areas of vegetation that shield and protect streams—are to healthy fisheries.

I stayed at the release longer than I planned because the kids were so engaged and impressive. To be certain, Sandy is an exceptional teacher. And Chuck, who drives around with a home-made trout cooler in his car, is not your average volunteer. Still, it made me reconsider and appreciate Trout in the Classroom as an effective tool to engage kids in conservation.

Trout Unlimited should, and will, advocate for native and wild fish (and work with the states to raise native fish in TIC, as appropriate), but let us celebrate the countless Sandys and Chucks who are training the next generation of conservation advocates to care for and recover our shared lands and waters.

Chris Wood is the president and CEO of Trout Unlimited.