Portaging from lake to lake was a unique experience while fishing the Swan and Swanson lakes in Alaska. Daniel A. Ritz photo.

The Kenai National Wildlife Refuge was on fire, but the fishing was not

Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to reach the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge, attempting to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using #WesternTroutChallenge.

I landed on the shores of the Kenai River on a Friday in early June. Eric Booton, my newest friend and taxi driver extraordinaire as well as sportfishing outreach coordinator for Trout Unlimited Alaska, was concerned the nearby campground would be full.

“Is it always this busy here? On the Kenai, I mean?” I asked Booton.

“Today’s the rainbow opener. I’ve been watching guides and fishermen count down to it for weeks. Everyone’s hungry. Not to mention the reds (sockeye salmon) are starting to come in,” Booton explained.

Thankfully, and purposefully, I wasn’t there for trophy rainbow trout. Or salmon.

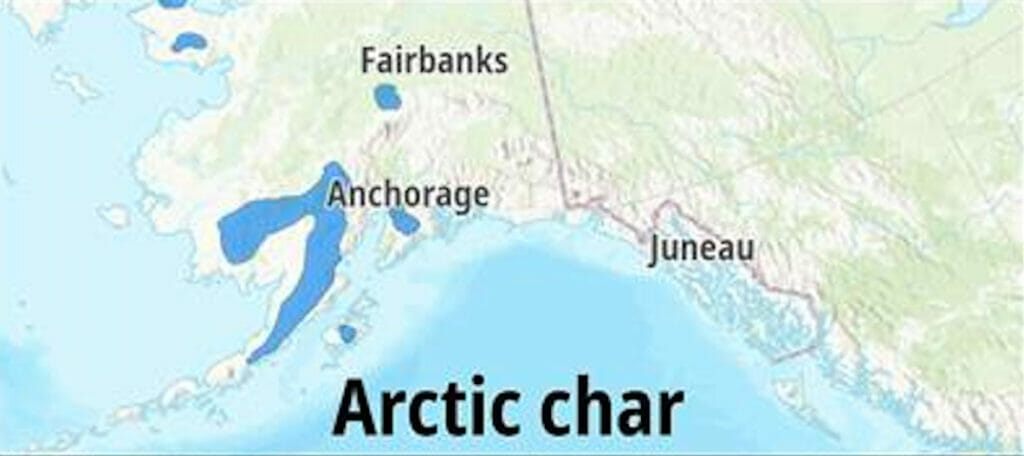

Centrally located on the Kenai Peninsula, almost perfectly placed between the Moose River and Swanson Rivers was Sterling and the nearby Swan Lake and Swanson Lake systems within the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge.

The Swanson and Swan lake systems are connected largely by a system of canoe trails and portages.

For those of you who are not aware of what a portage is, that is when you paddle across a body of water, get out on the other side, put the canoe on your heads and carry it to your next body of water.

Within these lake systems are a healthy population of genetically pure Arctic char, the sixth and last of the native trout species I intended to experience while in Alaska looking to add fish for the Western Native Trout Challenge. After successfully managing to attain the first five species, I was full of confidence with four days remaining in my trip.

My host and partner in my pursuit of Arctic char was Dave Atcheson. He is a former professor of fly fishing at the University of Alaska Anchorage Kenai Peninsula College and also author of National Geographic’s Hidden Alaska: Bristol Bay and Beyond, and the guidebook Fishing Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula. He is actively writing a guide style book covering the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge’s hundreds of lakes and respective canoe systems.

Atcheson picked me up from my campground on the Kenai River, taking me to the cabin he, his wife Cindy and his two dogs call home.

“I told Cindy we’d be fishing all day tomorrow, but I’m going to see if we can sneak out tonight. See if we can’t get you that char,” Atcheson said with a twinkle in his eye, like a child preparing to pull off a mischievous stunt.

We did manage to get out in the canoe that evening. My first lesson in fishing out of, maneuvering and transporting a canoe came in Paddle Lake in the Swan Lake canoe route.

If you haven’t fished out of a canoe before, please take my advice and practice before you anticipate a successful fishing session. Despite my line slapping, incessant tangles and nearly constant equipment juggling, we managed to catch the other prominent species of these lakes, wild and native Alaskan rainbow trout.

We caught more than a dozen rainbows each in just a few hours.

“Looks like a good way to end a day to me,” Atcheson said casually as we doubled up.

As we returned back to the cabin, excited to put in a full day on a loop to include five different lakes that Atcheson had caught a number of char in, a quick squall of rain rolled in and thunder rolled.

The next morning, I woke up in my guest cabin to Atcheson texting me in the cabin that coffee was on.

Walking into the house, Atcheson informed me that he was concerned about our access to the lakes. The lightning from the night before, which we only quickly experienced at the very tail end of our fishing session, had started a fire. The Loon Lake Fire was burning less than a mile from where the Swan Lake Fire burned almost 175,000 acres of the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge and the surrounding area almost exactly two years prior in June of 2019.

We quickly packed the canoe and gear atop Atcheson’s truck and headed out to see where we would be able to fish.

My heart raced as we proceeded down the almost 15-mile Swanson River Road. We kept expecting to be turned around any minute. Knowing there were so many lake options with confirmed populations of char, I had a lot of faith one would offer me the opportunity to bring an Arctic char to hand. The problem was, the bumpy pothole strewn dirt road was, as far as I knew, the only artery to the lake systems. If this fire got out of control, as the 2019 fire did, I could be shut out.

We managed to make it uninterrupted to the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge canoe lake system. We were headed to Spruce Lake, deep into the interior of the Swan Lake Canoe Route, allegedly holding healthy char numbers, and where Atcheson had past success.

As we paddled, Atcheson assured me that it was just a numbers game.

“It might even be 20 to one, but if you fish long enough, you’ll pull up a char,” Atcheson repeatedly stated. “I mean, nothing’s guaranteed. It’s fishing, but, you’ll find a char. I know it.”

In fact, my initial concern when learning about Arctic char was not locating or catching them, it was ensuring that it was in fact a genetically pure Arctic char. Anglers often mistake Arctic char with their char cousins Dolly Varden.

Months earlier Atcheson sent me an article he had produced that had been published years earlier.

In it, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Jack Dean claimed, “In the Swanson watershed this population may have originated from ocean going, or anadromous, Arctic char that made their way into the lakes after the last glacier melt off some 13,000 years ago. Another theory suggests that they may have even been present long before this, surviving in ice-dammed lakes.”

Full of the confidence brought about from bright skies and nothing but full days of fishing ahead, Atcheson and I proceeded to paddle and carry the canoe miles to our destination lake.

For the next eight hours, as the dark smoke of the Loon Lake Fire loomed in the background and planes swirled overhead, we combed the edges of the lake and a pounded lily pad flotillas.

We caught 30, maybe 40 rainbows that day. A few of them even of respectable size and putting up honorable fights.

My little experience in Alaska had already taught me that char tend not to jump as much as their rainbow brethren, so each time I would feel the line pull taught, I would say “stay down, char,” as if I was scolding a misbehaving golden retriever.

One after another, to my disappointment, they would leap in the air, as if to antagonize me.

Before heading out the next day, Atcheson and I had reached out to a few agency biologists and friendly contacts who suggested additional destinations.

One was, ironically, Dolly Varden Lake, a roadside lake with a campground. A friend of Atcheson’s, a pilot and fellow angler, assured him if char were anywhere, they were there.

My spirits lifted, I immediately drove my borrowed car, now loaded with a single person pack raft and as little gear as I could manage, to Dolly Varden Lake.

I arrived at the lake to see no one on the water and only one boat pulling out of the water.

Anxiously lugging the raft and my gear down to the boat ramp, the captain of the lone boat, introduced himself as George “Bubba” Hunt.

He seemed nice enough, and I asked how he did.

“Oh, they’re hot out right now. You are going to have a blast,” Hunt remarked.

“Oh yea? What’d ya’ get?,” I ask, attempting to hide my excitement.

“Char,” Hunt said emphatically. “All that is out there.”

With that, I asked Hunt, a published author and a moose-call maker, to carefully articulate where he was fishing. We triangulate positions, he shakes my hand and wishes me luck.

“Wait. Sorry. Last thing. What did you hook ‘em on?” I asked, having officially lost any sense of pride.

“Trolling swim baits,” he said without hesitation. “Ran ’em about 20 feet down right across that drop-off. Nailed ’em. Wanna see ’em?”

He brought me on board the boat. Inside a Ziploc bag were five radiant, healthy Arctic char, gutted, ready for the pan.

I saw them with my own eyes. They were here. My heart soared. In that moment, nothing else mattered. I was going to be home by lunch.

For the next five hours, I toured the drop-off Hunt had described. Back and forth, front to back, shallow to deep and from deep to shallow. Weighted flies, sinking lines, sinking tips, green buggers, black leeches, bait imitations, big streamers and small nymphs.

I threw everything I had at this channel. Not even a nibble.

When the wind came up, I returned to Atcheson’s home to grab a bit more lead and the bag we had used for an anchor.

“I’ll be back,” I told Atcheson. “They’re there. I just need to get to them.”

The remainder of that day and for the next 36 hours, until I was forced to pack my bags, the wind ripped. On the small pack raft, I was unable to maintain position long enough to allow my fly to sink to the desired depth. I don’t want to make excuses. I’m sure the famed Phil Rowley could do it with his eyes closed, but I threw everything and the kitchen sink in the waters of Dolly Varden Lake and came away empty-handed.

The night before I had to depart, hoping the wind would die as the sun “set,” I fished from 10 p.m. until 2 a.m., combing the shores of the lake. As the screaming children and barking dogs of the campground settled in for the “night,” I ventured farther and farther from Hunt’s original sweet spot. On the other side of the lake, directly across from the boat ramp, I could see I was in a shallower bay.

Exhausted, I did my best to put myself on the ledge of the drop off without putting myself into the path of the wind. I set up a sinking tip and tied on what felt like would be a lucky olive green wooly bugger.

Finally, a bite and it didn’t jump. I remember it didn’t feel particularly large but by that point, mentally and physically, I didn’t care.

I brought the fish beside the raft, careful to keep the rod tip high so as to not lose the fish on the barbless hook.

It turned out to be a 10- to 12 inch rainbow. I released it without touching it and slapped the water with my net.

I dejectedly paddled the raft nearly a mile back across the lake directly against the wind, knowing that my time to catch an Arctic char was over.

As I paddled, I sat long and hard with myself, spiraling in self-loathing with my decision to forgo more popular and consistent Arctic char fisheries. I could have gone north from Fairbanks where they fish for the larger northern form of Arctic char. Instead, I had chosen to pursue Arctic char in a place no one had ever heard of and where I often needed to explain their existence.

At the moment, my triceps cramping as I neared the boat launch, I was overwhelmed with my own hubris. Who did I think I was? Who was I to go and try to prove something? I had never even been to Alaska. Why did I think easily accessible experiences were too good for me.

It took me some time to really boil down why, but while traveling back to the airport, I realized I had chosen to pursue Arctic char on Swan and Swanson lakes because I didn’t want to go to what very well may be the “Last Frontier ” and check a box.

I loved that when I told people I was destined to wrap up my journey in Alaska on the Kenai Peninsula, people had to tell me their favorite salmon story or how a 35-inch Alaskan rainbow hit their spoon like a hammer. Not to say there isn’t value in those experiences, not taking anything away from it, but my assignment on this project was to showcase the habitats and the native trout species of the West. I had attempted to share a little known, scientifically unique population that lived in one of the most beautiful landscapes I had ever experienced.

Let’s call it what it is, I had failed in catching the fish I had set out to find, but I felt better knowing that in a land ripe with genuine opportunity for discovery, I chose not to do the same thing someone else had done.

I suppose, at the end of the day, there was something paradoxical about coming to Alaska and having everything be a sure thing. Either way, like Atcheson said, you can’t guarantee anything. That’s fishing. And that’s what has me looking forward to my next trip to Alaska.