What rainbow trout can teach us about engaging native fish, salads, diversity and river towns

Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to reach the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge, attempting to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using #WesternTroutChallenge.

As I slowly descended from the high desert into California the thermometer in the truck showed 117-degrees as I crossed the border from Arizona into the bleak landscape outside Needles.

I was headed to Kernville, Calif., a few miles west of one of my favorite thoroughfares in the entire West, US-395. Highway 395 passes directly through the shadow of Mt. Whitney–the highest mountain in the contiguous United Statets — as you pass by the breathtaking southern Sierra Nevada range.

Life in Kernville revolves around the river and, upon arriving in town, one could easily see that revolution was slow. Temperatures had been above 100-degrees since before anyone could remember and the generally abundant runoff from the Sierra Nevada mountains enveloping Kernville and responsible for the formation of the Kern River had been gone for months. The air burns the throat and it was eerily silent. No children were playing on the riverside. Dust swirled in the street and the abundant outdoor patios built for tourists to enjoy the world-famous California sun were all empty.

The day before my arrival, I made a call to my college roommate Steve Merrow, a world-class whitewater rafting guide, who now works for Sierra South in Kernville.

“They just lowered the release on the dam for the (Lower Kern River),” he said. “Yesterday they lowered it to about 90 cubic feet-per-second (CFS), essentially ending my season. Looks like I might be able to hang out a little bit more now.”

After hanging up the phone, I was shocked by his calm demeanor as he casually told me there wasn’t enough water to support his and most of the town’s way of life. I suppose he had been suffering the consequences and preparing for this loss for some time.

While I knew that my old friend was a devoted riverman and skilled navigator, I also knew he didn’t know his ass from his elbow about trout fishing so almost immediately after getting into town, I walked around the corner from his house to Kern River Fly Fishing.

Upon entering the famous fly shop, I was greeted by Rob Buhler, a guide and fly tier for Kern River Fly Fishing. I introduced myself, explaining my project while desperately attempting to show that I had done my research and humbly deserving of his infinite mercy and pity.

You see, I was in need of serious help.

“I had a plan. But, everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face,” I told Buhler, quoting heavyweight champion Mike Tyson.

“Well, you’ve come to the right place, and I’m the right guy,” Buhler quickly responded. “I don’t have easy answers for you, but I have some ideas.”

My experience with Buhler was one of those defining moments that exemplified why I firmly believe a “shop” is different from a “store.” The long-haired and soft-eyed Buhler walked me around the shop showing me various topographic maps and detailed trails.

As Buhler showed me the “usual” spots, all the standard and most easily accessible areas to pursue California’s native trout, I realized in a way, the walls of this fly shop contained answers to all the secrets anyone could ever need. The conversation, the customer service, the community, that was icing on the cake. The keys to unlocking the experience of Kernville’s native trout were literally plastered on this building’s walls if you took the time and knew how to read them.

Sadly, a majority of the easily accessible spots were seeing extraordinarily high water temperatures and even some fish kills at the more stagnant sections.

“If I was you, I would head up to Johnsondale Bridge and hike north well into the canyon,” Buhler said. “There are some stocked rainbows that might be sprinkled in as they are getting moved around with the low water and high temperatures in the lower section below the diversion dam, but if you get in that canyon a few miles, that’s where you’ll find the natives. And trust me, there’s no mistaking them.”

Over the course of my career in journalism, this is a mistake I’ve learned that I have a tendency to make. When someone tells me that something will be obvious, for some reason, unknown to me, I trust them. In fact, it is almost never obvious.

However, on this occasion, intuition served me and Buhler’s advice was sound. After hiking more than 3 miles upstream through the evening California sun to beat the midday heat, I came to a beautiful section of pocket water with cool waters.

It wasn’t long until my oversized yellow stimulator disappeared below the surface of a pool behind one of the now-exposed giant boulders that would normally be an underwater feature of the river for kayakers and rafters.

The fight was on, even before seeing it there was no mistaking it was a wild rainbow.

Historically, the Kern River rainbow was once the most abundant and widespread trout in the upper Kern Basin and grew to large sizes. Since the 19th century, over-exploitation, combined with habitat degradation and, most importantly, hybridization with other trout, the population has been reduced to a small fraction of historic numbers.

To add insult to injury, not only are Kern River rainbows susceptible to hybridization with the two subspecies of golden trout that naturally crossover, Kern River rainbows are often misidentified or at least not recognized as unique as a species native and unique only to California due to the prevalence of stocked rainbow trout raised in hatcheries and then released all over the world.

This particular juxtaposition was really interesting to me. I have never, and likely will never be able to claim to be a taxonomist, geneticist or biologist, but the public acceptance of “rainbow trout,” as a blanket and overarching name for a species undermines the uniqueness of the California native trout experience.

While it is understood that the original hatchery and therefore hatchery-origin fish for stocking purposes were McCloud River rainbows from northern California, the history of the rainbow trout in its native California waters is dynamic, complex and very interesting.

It is my understanding that. at their root, all rainbow trout can originally be traced to coastal rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus). Geologic history, along with individual pressures, has resulted in various genetic isolation events causing differentiation to the point where the Kern River rainbow are more genetically similar to its Kern River and Kern River adjacent species the California golden trout and Little Kern Golden trout than the coastal rainbow trout.

Interesting as it is, I’ve affectionately said a number of times while researching this project that genetics “isn’t the hill I’m going to die on.” My interest in the native rainbow trout of California, of which there are a few varieties in addition to the Kern River rainbow, wasn’t purely taxonomic in nature.

Back on the upper Kern, I quickly got my fish to the net as the sun was setting behind the canyon’s western wall.

Buhler was right. There was absolutely no mistaking it. The Kern River rainbow has a vibrancy in color, all of its colors, that simply isn’t present in its hatchery imposters. The back of the fish was more densely clustered with darker and more defined spots, the rose coloring along its lateral line was more clearly defined and the most telltale mark, the white edges along its fins, were clearly defined.

Unfortunately, there is a very real chance that Buhler won’t be able to make that claim, and anglers won’t be able to trust it, for much longer.

CalTrout says there are indications the Kern River rainbow trout could become extinct as a genetically unique species within the next 50 years.

As the sun continued to set and the air temperature continued to drop, I thought of how long a hike I had to get back to the truck. Along that long walk back, I thought of a story that Roger Bloom, the Inland Fisheries manager for California Department Fish and Wildlife, had told me weeks earlier during a phone interview.

Bloom shared that back in the early 1990s he worked for the wild trout program and attended many fishing expos and meetings. He remembers that the California Department of Fish and Wildlife had a poster with the native species.

“They would say ‘I’ve caught a rainbow, a brown and a brook,” Bloom said. “For 98-percent of people, the California natives were the fish they were yet to catch.”

He said it was then that he felt as if maybe he was failing. It seemed as if Californians were identifying with and embracing invasive species first — leaving their native counterparts as apparent afterthoughts.

In turn, Bloom focused on highlighting the native trout species of California. He pioneered the California Heritage Trout Challenge where anglers are challenged to catch six of California’s 11 recognized native trout species.

After my own successful encounter with a Kern River rainbow, I returned to home base in the dark where I attempted to explain the complex story of California’s rainbow trout, the associated modern subspecies, threats to their identities and why chasing natives is so darn fulfilling to my former roommate.

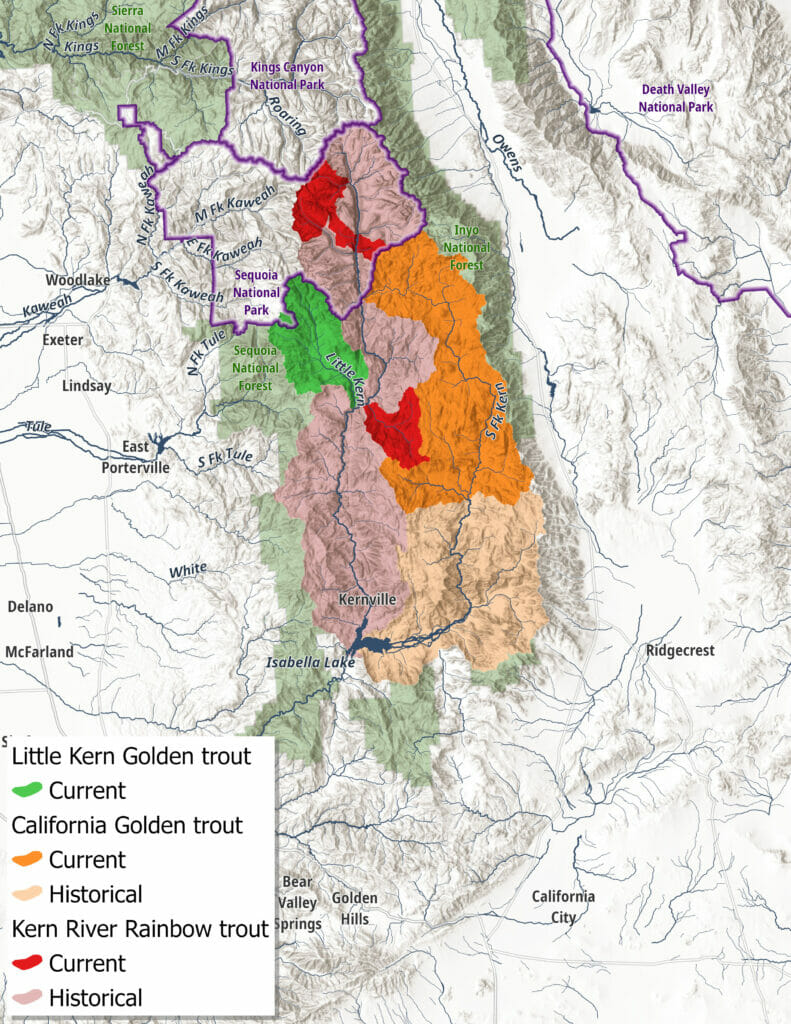

I showed him a map and pictures of the native trout historically present in the waters he frequents each and every day.

“They are so beautiful,” I caught him muttering repeatedly. “And they all look so different. That’s crazy, considering how they’ve developed side-by-side and so close to one another.”

“At the end of the day, isn’t it all just inevitable, though?” Merrow asked. “Won’t everything just slowly lose its individuality and become a genetic mix of everything?”

After a long pause, I let out a long exhale and in a sort of “here goes nothing” motio I offered what I thought was a brave criticism of the “melting pot” metaphor for cultural diversity. Did I mention I’m also not a sociologist?

“Naturally, I think a healthy river system operates more like a delicious salad than a melting pot,” I told Merrow. “Sure, sometimes, natural overlap will occur, you’ll get a bite with two ingredients, and they could be toxic, or delicious together. Just because they are in the same bowl, doesn’t mean that individual pieces lose their individual flavor or shouldn’t be appreciated for their own place in the bowl. I would think the goal of any good dish is to accentuate all of the flavors without eliminating any.”

You could call the radical pace at which the American West is changing a blessing or a curse, but that night, I realized that what I was experiencing, from right in the center of what could be called the geographical icon for the melting pot model, I was appreciating the unique flavors of a true Californian salad. Flavors that had been rich and beautiful and complex in flavor since long before my time.

As a society, an overly simplistic summary could say we are attempting to move towards a cultural mosaic model of inclusion that celebrates uniqueness while healthily acknowledging equalness.

I for one think that is a progressive move.

These days, to be assured you are getting a genetically pure Kern River rainbow trout, you may have to hike many miles. Metaphorically, while connecting with California’s native trout is only becoming more difficult, I hope Californians consider the beautiful native species right underneath their noses before organizing their next destination fishing experience.

Like how Buhler confidently and correctly told me I would “just know” the difference between the hatchery and wild Kern River rainbows, I assure you, when you embrace the experience of California’s native trout –including the Kern River rainbow trout — you’ll “just know” why it’s important not to let them slip away. Losing just one of the individual flavors of California’s biological salad could really throw a beautiful thing out of balance, much like the oppressive heavy feeling throughout a river town without a river.