Rough roads and spooky golden trout in California

Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to reach the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge, attempting to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using the #WesternTroutChallenge.

It was just after 4:30 a.m. when Steve Merrow and I swung by Sierra South in Kernville, Calif., to grab a few shovels.

Why were we raiding my friend’s company shed for shovels at such an ungodly hour? We were in a race against the sun to climb more than 6,000 vertical feet above his Kernville home in order to pursue one of the most beautiful trout in the world in their native habitat.

The fish formerly known as Volcano Creek trout, California’s state fish, the California Golden trout, persist high in the Sierra near Merrow’s home.

I was admittedly nervous. Apparently, California golden trout require healthy 4X4 vehicles to visit their native homeland. Numerous people warned us of the trail ahead.

“Bring an inReach (Garmin) because if you get stuck,” one man told me, “you ain’t getting out.”

Throughout the creation of this series, I’ve been genuinely impressed by how many people ask me if/when/where/how I am going to catch golden trout. To my surprise, it is by far the most asked about and recognized species I’ve been encountering.

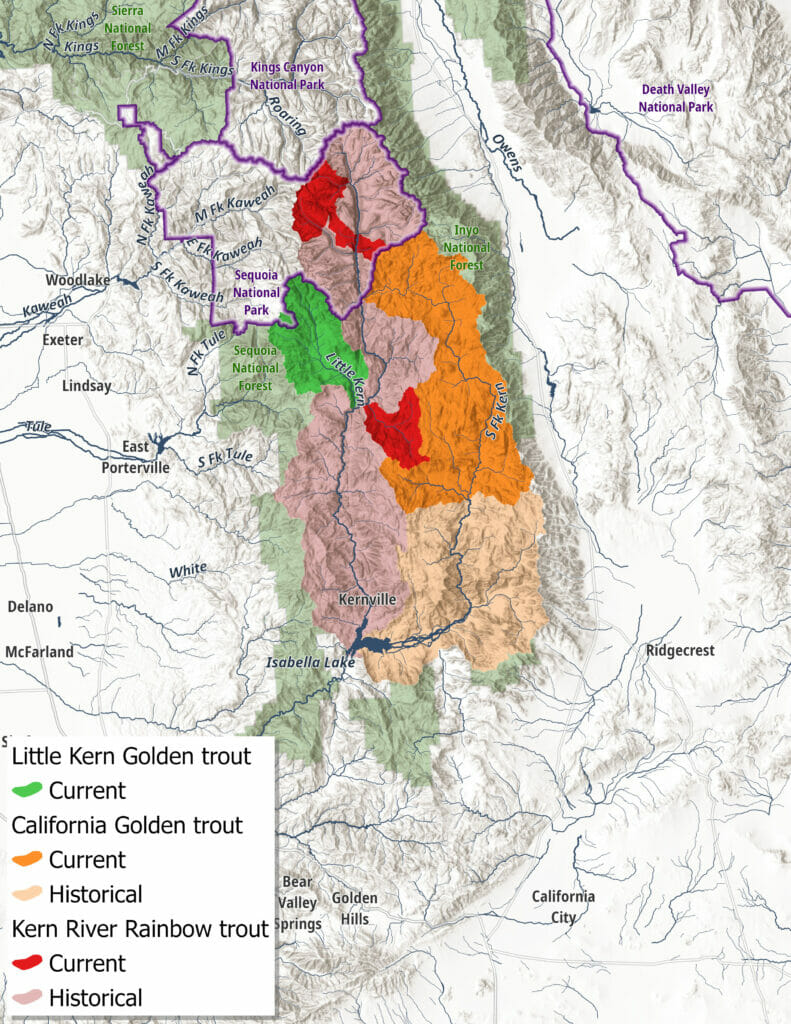

I’m largely surprised because often, the people asking are shocked when I tell them I will be pursuing them within their native home waters in California. I then explain that in fact, the species I am pursuing is the California golden trout, native to a number of formerly interconnected watersheds of the Kern Plateau.

“Golden trout are from California? Well, I’ll be damned,” more than a few anglers I will leave unnamed have commented.

That all being said, I had a plan to pursue California golden trout in a few relatively well known and easily accessible streams within the Golden Trout Wilderness north of Kenville. California goldens seem to be relatively abundant and take easily to any dry you offer them that they can fit in their mouth.

What could be so hard?

That was before low water. One day before my arrival the water was lowered in the Kern River to 90 cubic-feet-per-second. On top of that, Kernville reached 110-degrees for my entire 4-day stay and had not fallen below triple digits for weeks.

I put my tail between my legs and walked into Kern River Fly Fishing and asked fly tier Rob Buhler, for help. My initial native trout species pursuit plan was absolutely out the window.

“Well, I have some answers for you…” Buhler quickly responded, “but none of them are good.”

Low, warm waters forced Buhler to recite a list of all the water that would be irresponsible to fish–almost all of the spots I had researched. A few of what Buhler called the “go-to” spots had unfortunately even seen beautiful California golden trout going belly up due to already oxygen deficient and now stagnant water conditions in some parts of the Kern.

He did have one idea, though. Buhler walked me outside the shop to a large topographic map on the exterior wall.

In that way that is hard to follow when someone knows a trail well and you’re trying to follow along, Buhler proceeded to drag his index finger through what looked like an impossible trail around, up and over a surrounding section of the Sierra, through Sequoia National Forest into Inyo National Forest to the headwaters of the South Fork of the Kern River.

As hard as it was to believe, there was really no other option.

So, long before dawn, Merrow and I left his home in Kernville, stocked up on water and rescue equipment and hit the road northbound. We followed the Kern River until hitting Sherman Pass Road and beginning our ascent.

We climbed for what seemed like hours, with Merrow, who also had never been to this area, playing tour guide, pointing out the various wilderness spaces and landmarks in the now clear horizon.

After roughly an hour and a half, we pulled onto a loosely marked “dirt” jeep trail that is largely just a series of rocks that a vehicle’s tires can pass from one to another. Only 7 miles long, the hair-raising downhill rock scramble takes almost an hour.

We emerged from the rocky death trap into a high alpine meadow plateau entering the Inyo National Forest. Catching a glimpse at the South Fork of the Kern River, our destination, was made intensely more gratifying as Mt. Whitney – the tallest peak in the lower 48 states, could be made out in the background.

“I see a trout!” Merrow called out as I was distracted by the scenery. He is a world-class whitewater rafting guide, but will readily admit not a fisherman, so I rushed over to confirm.

A beautiful trout, maybe 12 to 14 inches long, lurked partially beneath an undercut bank feeding heartily. Full of confidence having located our target after such a mission, I quickly tied on a small caddis imitation and told Merrow to step to the side.

“Watch this,” I said for some reason. I had not seen my dear friend in years and was thrilled to show him what this was all about. It sounds silly now, but I was excited.

I pitched an uncharacteristically accurate cast and like it was scripted the trout leapt from behind the bank to engulf the fly. While expounding to my friend about how easy this was going to be after such hard work to get there, I was speechless when I got the fish to the net and saw it was a beautiful, wild but non-native brown trout.

I remembered reading somewhere that hybrid and non-native species were more prevalent in the initial stretches of the high alpine meadow where we were. I tell Merrow that we were going to head upstream a bit further. I’m sure by now he wondered what he had gotten himself into.

Moving upstream we found wider, flat waters where the riparian zone had been badly beaten by cattle into a more defined stream with stronger banks.

As the sun continued to rise, I began to feel anxious about responsibly connecting with this species. Sure, they will apparently take anything you give them, but should I? At almost 10,000 feet in elevation, I checked the water and was pleased to see it was even colder here than where we had started.

The bends and pools with undercut banks were clearly defined. Walking up carefully to the first of likely spots I saw maybe 40 to 50 very clearly defined California goldens. Their hallmark par-marks and crisp lines were clear as day.

Unfortunately, I was apparently as easy to spot as they were. For the next hour Merrow and I tried unsuccessfully to stealthily get to some sort of reasonable casting distance without spooking large schools of fish. It didn’t help that shortly after 8 a.m. the wind came ripping directly downstream, making almost any sort of upstream cast next to impossible. With no cloud cover and a rising sun, we were clear as day to the fish. We couldn’t get within more than 20 to 30 yards of the stream without seeing the pools become cloudy as dozens, maybe hundreds of 6- to 10-inch fish scattered.

Finally, we found a bend in the river with a deep tailout section that was blocked from the wind.

“Want me to go look at it?,” Merrow asked me. I told him to stick back. There’s no way there weren’t fish in there. I didn’t want to risk it.

Twelve feet of leader. 5X tippet. A barely visible CDC dry. Nearly four hours of driving and years taken off the life of my F-150. It wasn’t supposed to be this hard.

From my knees, I made a long cast directly over the tailout and almost immediately a red and yellow fish flew out of the water, fly in mouth.

“Did. You. See. That. Red?….,” I yelled to Merrow, …”now that’s a golden trout, for sure.”

I quickly landed the fish in the net. Merrow and I both remarked about its vibrant markings.

We moved only slightly further upstream and caugt only two or three more fish before calling it a day. As the sun rose higher in the sky, we felt the intensity of the sun increase and knew that with it would come warming waters.

The wind was howling, and in that remarkably beautiful and relatively untouched wild space, I couldn’t help but like an intruder.

“Oh man, sorry I didn’t say anything about how spooky they are up there!” Buhler chuckled when I went back to thank him for the inspiration the day before. “This year, with it being so hot, they’re in total survival mode up there.”

It’s impossible and probably irresponsible to anthropomorphize the feelings of an endeared native trout species such as a California golden trout. As I look back at that day, I realized that in a way, our adventure into the wilds up, around and above the Kern River allowed me to exercise my own survival instincts a bit.

Sure, there are hybridized, easily caught and stocked California Golden trout from Idaho throughout Wyoming and many, many more locations. But, at the heart of their native territory, I had to kick it into survival mode just to experience California’s state fish.

I’ll never just call it a “golden trout” again.