The Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps made a curious admission in 2020. They announced they were removing the protections of the Clean Water Act for ephemeral streams, which only flow in response to rainfall. They then said they were unable to determine the potential effects of this dramatic change.

The chief of the EPA Office of Water at the time said, “If you see percentages of water features that are claimed to be in [the new rule], or reductions, there really isn’t the data to support those statistics. No one has the data.”

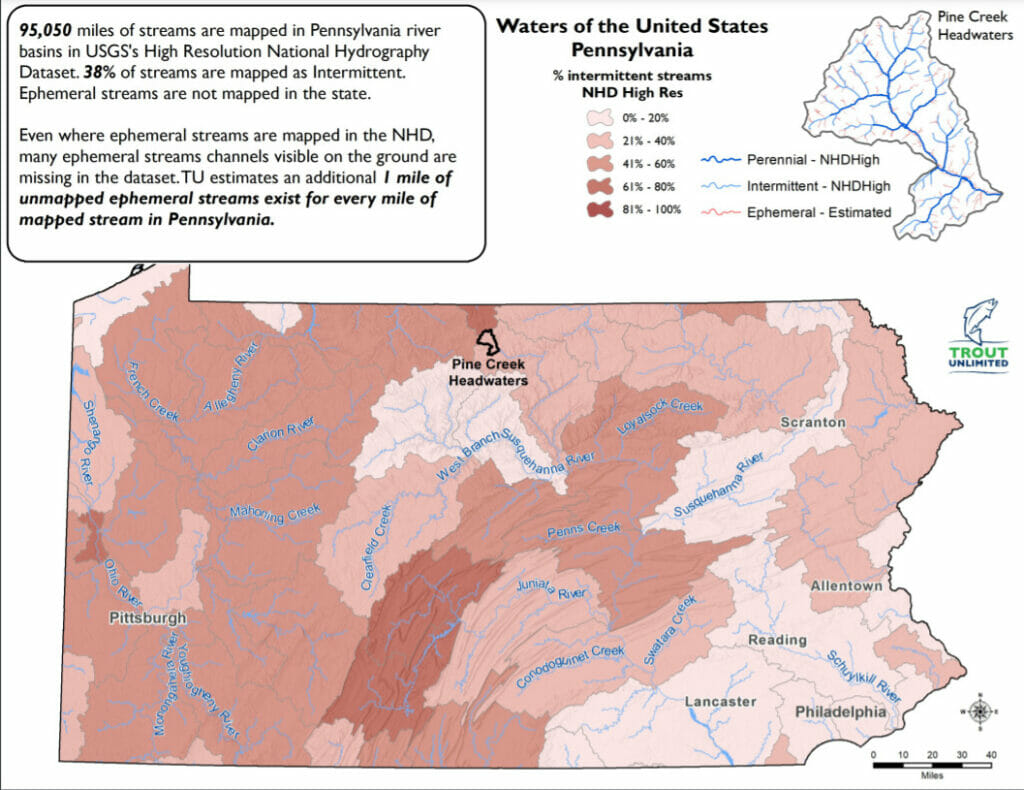

TU scientists stepped into this void, and based on existing data estimated that nearly half of the stream miles in the lower 48 were classified as ephemeral waters. These were left unprotected by the Clean Water Act under the new government policy. TU’s scientists later published their findings in the peer reviewed journal, Freshwater Science.

No data. Really?

TU scientists estimated that approximately 4.8 million stream miles, or 48 percent of stream channels by length in the continental U.S., are ephemeral. None of these waters would benefit from the protections of the Clean Water Act. Nor would some intermittent streams that flow only seasonally.

These waters make up 60 to 80 percent of the total stream mileage in a basin on average, but the percentages are much higher in certain regions and watersheds. For example, in the southwestern United States, over 81 percent of streams have ephemeral or intermittent flow. Modeling suggests that greater than 85 percent of stream miles in some New Mexico watersheds lost protections under the 2020 rule.

Look before you leap

Happily, this week, U.S. District Judge Rosemary Márquez found Trout Unlimited’s arguments compelling and declared that the 2020 rule was illegal and “would cause serious environmental harm.”

Anglers should celebrate Judge Márquez’s ruling, because we understand the importance of weather-dependent streams to the health of larger rivers downstream. Seasonal streams can provide important nutrients and sources of cold, clean water for larger waters downstream. They can also transport pollutants if not managed properly.

Consider my family’s place in West Virginia. We have an ephemeral stream in front of our home. A few years ago, we had a massive rainstorm and the creek rose four feet in an hour. The flood carried away a bridge I had built on railroad ties, and buried it 600 yards downstream under several feet of dirt and rock.

The power of that flood made it obvious that we all live downstream. That creek would be a lot less of a cool place for me and my kids to look for frogs, bugs, and snakes if the Clean Water Act did not require my upstream neighbor to keep his manure lagoons away from it.

The Clean Water Act is the classic look-before-you-leap law. It requires that landowners, farmers, and developers take common-sense precautions and get permits before developing near streams. Why is this important? Everything we do on the land is eventually reflected in the health and cleanliness of our rivers and streams.

Looking back, looking ahead

Clean water is not a political issue. It is a basic right. No presidential administration can stop water from flowing downhill. For the first several decades after passage of the Clean Water Act, the law’s protections were accepted to extend to small and large streams alike. In 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that for the Clean Water Act to apply, small streams and wetlands must share a “significant nexus” with larger navigable waterways.

The Obama administration finalized a rule in 2015 based on a scientific review demonstrating the connection between small streams and downstream navigable waterways.

The Obama rules were scrapped by the Trump administration. The Trump administration’s rules have now been scrapped by the judicial system.

The Clean Water Act protects rivers in two ways. First, it regulates the discharge of pollution from factories, for example, into rivers. Second, it addresses the impacts of development, such as subdivisions and road construction projects that fill in or pave over water features. To be effective, the Clean Water Act must be able to control pollution at its source, upstream in the headwaters and wetlands that flow downstream through communities to our major lakes, rivers, and bays.

Protecting small headwater streams helps to reduce downstream water filtration costs for local communities. It can temper downstream flooding, and help prevent damage to homes, businesses, roads and bridges.

Getting it right. Finally

Just as my family has the right to expect that my upstream neighbors will comply with the rules of the Clean Water Act for ephemeral streams, my neighbor has the right to support his family through his farm. The challenge for the EPA, and it is not a new one, is to develop a set of rules that keep or make downstream waters fishable and swimmable while also providing the certainty and predictability that farmers, developers, and others need to make a living.

The Biden administration inherits a deep administrative record associated with two prior rules. It also faces several deeply-divided constituencies. Creating a process where farmers, developers, and others can make their voices heard, while also paying attention to sound science, will ensure a stronger and more durable set of rules for implementing the Clean Water Act.

In the meantime, we should celebrate a victory for common sense and engage with the EPA’s new rule-making process to protect small seasonal streams while also providing a clear set of rules for farmers, ranchers, developers, and others.