Mining in the Yellow Pine pit began in 1938 and has blocked fish passage to the upper stretches of the river ever since. Photo by Daniel A. Ritz

Editor’s note: Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to accomplish the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge. He will attempt to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using the #WesternTroutChallenge.

The combination of a helicopter humming just over head and the sounds of nearby voices woke me.

After receiving marching orders from my fiancé not to come back until I caught a bull trout, I drove through the night from my home in Boise to the 3,000-acre Stibnite/Yellow Pine Mining Area.

I had hoped for, and expected, an uninterrupted slumber.

Located along the East Fork of the South Fork of the Salmon River, 14 miles southeast of the Idaho town of Yellow Pine, the Yellow Pine pit is affectionately known as “Stibnite Lake.”

As I emerged from the bed of my pickup, a small group of maybe a dozen men and women in hardhats and polos looked at me as if I was a real-life trucker-hat-clad zombie. They let their hackles down after I introduced myself and they explained a crew from CBS was at the site to record what they referred to as a “public relations” video.

Overhead, a helicopter raced back and forth over the northern rim of the abandoned pit dumping water on a small, but completely uncontained fire just north of river.

Through all the commotion, I realized that right there, smack dab in the middle of nowhere, I was in a conflict zone for some of Idaho’s most valuable natural resources.

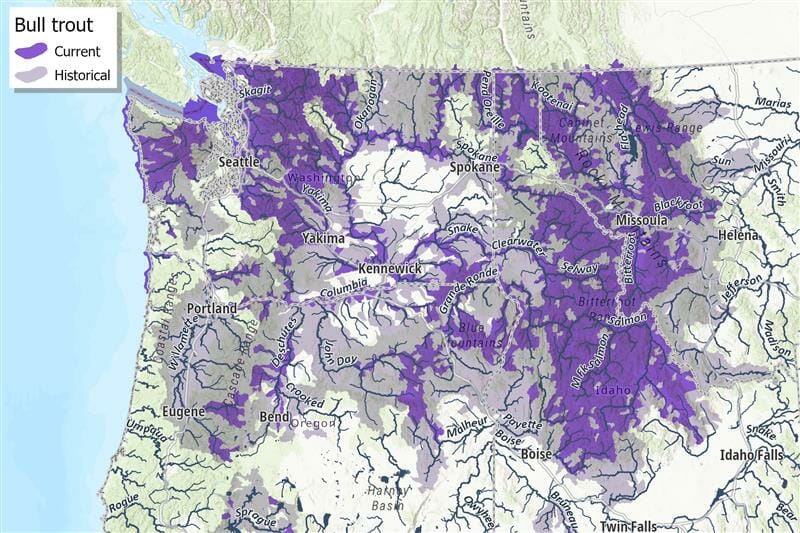

My search for bull trout had literally been years in the making. Despite living in Idaho, where we have a number of what Idaho Fish and Game Sportfishing Program Coordinator Martin Koenig described as “robust and stable populations,” bull trout had taken on almost mythical persona as they continuously evaded me.

“Idaho is fortunate in that bull trout were historically and are still currently distributed throughout some of our large, interconnected rivers systems such as the Salmon and Clearwater. Because of this, we have robust populations and stable trends in some areas, so we are lucky in that respect,” Koenig explained. “But bull trout still face challenges in other parts of the state and there is still a lot of work to be done to sustain these fish into the future.”

Koenig went on to explain that his agency and partners have done habitat restoration projects, non-native fish management actions and research to address some of the challenges.

Through extensive phone calls and a little fly-shop eavesdropping, I narrowed in on the East Fork of the South Fork of the Salmon River. Knowing adult bull trout are predatory fish-eaters, I decided to drive through the early hours of the morning to fish in the low light of sunrise and increase my chances.

At Stibnite/Yellow Pine, bull trout have habituated to the deep and cold water of the former pit.

Jordan Messner, fisheries regional manager for Idaho Fish and Game, recognized that while this is not “ideal” habitat, the ability of the bulls there to habituate and create stable and resident populations in less than 100 years stands as testament to their perseverance.

Most bull trout are highly migratory, spawning in tributary streams where juvenile fish usually rear from one to four years before migrating to either a larger river (fluvial), lake (adfluvial), or ocean (anadromous) where they spend their adult life, typically returning to the natal tributary stream to spawn.

As I scaled the scree-covered walls of the pit, I realized a stark difference between this and many other species I had experienced thus far in my Western Trout Challenge journey. Not only are bull trout highly mobile, they are also almost nearly impossible to see in the water. Their coloring perfectly meshes with the deep waters in which they wait to ambush. Fishing for bull trout is the equivalent of shooting for a moving target that lives in hard-to-reach places that you often can’t even see.

With the shallow angle of pre-sunrise light, I was able to make out a flash of white as it appeared then disappeared again beneath a boulder deep in an outlet channel of the pit.

Precariously perched on the steep-sided outlet channel, I launched an awkward cast into the shallows of the tail of the pool upstream and allowed a heavy sculpin imitation to sink and jump along the bottom.

Unable to see my fly, I was worried I wouldn’t pick up on a take. I shouldn’t have been concerned.

My line ripped taut as something far under the surface inhaled my imitation and began to run with it like it had stolen something. I watched my line travel back and forth in the deep pool.

Overwhelmed with emotion, I literally slid down the awkward rock outcropping of the outlet channel and brought a 16- to 18-inch brightly spotted and beautiful bull trout to the net. Without removing it from the water, I snuck a few photographs and quickly released it back to the depths, watching its intense orange spots disappear into the deep blue of the bottomless pool.

I’m pretty committed to a one fish-per-hole fishing philosophy so, with the pressure now relieved, I decided to make my way around the rim of the pit to sample new waters. As the sun rose in the cloudless sky, I could see pods of 20- to 30-inch fish slowly sliding further into the depths for the day. Despite my best efforts, the shadowy figures did not come for my flies. The pools formed by the high-velocity entrance of the high-grade inlet stream into the pit — which has blocked fish passage for more than 80 years — offered only native westslope cutthroat trout.

Reconnection of the lower river — which now dead ends at the Yellow Pine pit, is one of many mitigation efforts being promised by Perpetua Resources (formerly known as Midas Gold Corp. until a rebranding in February 2021) as a part of its proposed Stibnite Gold Project.

The new moniker was inspired by Idaho’s state motto “Esto Perpetua” — from the Latin meaning “be eternal” — and is meant to more appropriately reflect a decision by the former Canadian company to focus on the U.S.

“We have always been more than a gold mining company, but you wouldn’t have known it by our name,” Chief Executive Officer Laurel Sayer said in a statement to Bloomberg. “Perpetua Resources better reflects our plan to restore an abandoned mining site, to responsibly develop the critical resources our country needs for a more secure and sustainable future and to be guided by a commitment to Idaho’s resources and people.”

On July 1 Perpetua Resources announced the U.S. Forest Service was “advancing Perpetua Resources’ modified proposed action in the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process and updated the permitting schedule for the Stibnite Gold Project (the Project).” The updated project schedule calls for the Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Study to be released in the first quarter of 2022.

Michael Gibson, Trout Unlimited’s Idaho field coordinator, has been offering comments at each step of the NEPA process to maintain standing as a stakeholder.

Whatever changes are to come to the East Fork of the South Fork of the Salmon and other bull trout fisheries in Idaho and beyond, Gibson suggested habitat impacts need to be analyzed within the standard of care that this unique species necessitates. He also noted that while groups like Trout Unlimited are active in engaging the upper echelons of bureaucracy, community voices will be essential in shaping the decisions to come about the Stibnite Gold Project.

“Stay informed and be aware of opportunities to comment as an angler,” Gibson said. “Our strength at Trout Unlimited is grassroots. We can add commentary and provide technical analysis, but they need to hear from the individuals.”

Back at the truck, I had decided to retreat from the clamor of the helicopter buzzing overhead and the Perpetua Resources employees offering the CBS crew cold lemonade. I moved downstream towards the town of Yellow Pine to try my hand at the few deep holes I had seen while driving up.

While water was generally low like most everywhere in the West this summer, I managed to find a series of deep holes formed by logs obviously placed there by an avalanche.

I tied a one-of-a-kind fly I had snagged from my friend Jeff Arterburn of Trout Unlimited New Mexico onto a sinking leader. I dead-drifted the flashback wooly bugger deep and as close as I could to a submerged ponderosa and watched with delight as a juvenile bull ferociously took the small streamer.

I chuckled to myself, laughing at how aggressive and fearless the little fish was. I thought of the trials it would see. Would it make it to the headwaters? Would it live to grow to be the size of the ghosts I saw disappearing into the Yellow Pine pit under the rising sun? Would it suffocate in warming waters? Would it be able to pass along its lineage to future generations of bull trout if any of the numerous potential environmental disasters noted by critics of Perpetua Resources Initial Draft Environmental Impact report occurred?

Brett Bowersox is a bull trout coordinator for Idaho Fish and Game. He works intensely with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to ensure Idaho’s bull trout populations and management practices adhere to the policies of the Bull Trout Recovery Plan.

When I spoke with Bowersox, he mentioned angler pressure in Idaho is not a primary threat to bull trout populations and supported Koenig’s claim that catch-and-release practices have been a successful regulation tactic since they were applied in the late 1990s.

“Anglers are such a positive conservation measure,” Bowersox said. “For folks to tangibly have the opportunity to experience the beauty of the fish and where they live is of such a high value. It can keep people engaged.”

After my pursuit of bull trout in central Idaho, I walked away glaringly aware of how we accept things placed in the universal and somewhat broad category of “natural resources”.

It would appear that in Idaho and, more specifically thanks to intensive work by fisheries managers like IDFG and USFWS, as well as the historic stewardship of Nez Perce tribe and responsible anglers, bull trout exist in a way not seen in many places in the West. They are undoubtedly rare and inarguably valuable. By encountering them, as I did, and releasing them to live on and pass on their lineage to the future, we can maintain the value of the land.

Gold, antimony and other critical minerals are no doubt of great financial value and economic importance. However, it would seem to me that if we are honestly focused on eternity, we should be careful to keep as much of the values in the land and in the waters of Idaho as we possibly can.

Editor’s Note: The author notes the importance of the opinions and statements of the Nez Perce Tribe. While representatives of the tribe were unable to be reached for comment at the time of publication, you can read more about of the Nez Perce and the Stibnite Gold Project here.