Eagle Lake rainbow trout are native to the high alpine watersheds of Lassen County, California. Daniel A. Ritz photo.

The Eagle Lake rainbow trout is the final fish as Daniel Ritz completes the Western Native Trout Challenge

Editor’s note: Daniel Ritz is fishing across the Western United States this summer in an attempt to accomplish the Master Caster class of the Western Native Trout Challenge. He will attempt to land each of the 20 native trout species in their historical ranges of the 12 states in the West. You can follow Ritz as he travels across the West by following Trout Unlimited, Orvis, Western Native Trout Challenge and Montana Fly Company on social media using the #WesternTroutChallenge.

Pulling away from my home in Boise just after 5 a.m. in late September, I realized the scale of the journey I was hoping to complete on this final trip.

Driving through the Owyhee region of southwest Idaho and northeast Oregon, and then across Nevada, I was overwhelmed by how the mountains, which had glittered with ice and snow on a previous trip, were now gold.

It was the third time I had traveled this route during my Western Native Trout Challenge series. This time, I was headed toward Lassen County, in northern California, to pursue and hopefully catch the oft-overlooked Eagle Lake rainbow trout.

If I’m being honest, it felt fitting. After coaxing cutthroat species after cutthroat species to dry flies on small creeks, having Alaskan lake trout testing my drag system and rare Arctic char test my patience, that my very last native species in my pursuit of the Master Class of the Western Native Trout Challenge was, in fact, a rainbow trout.

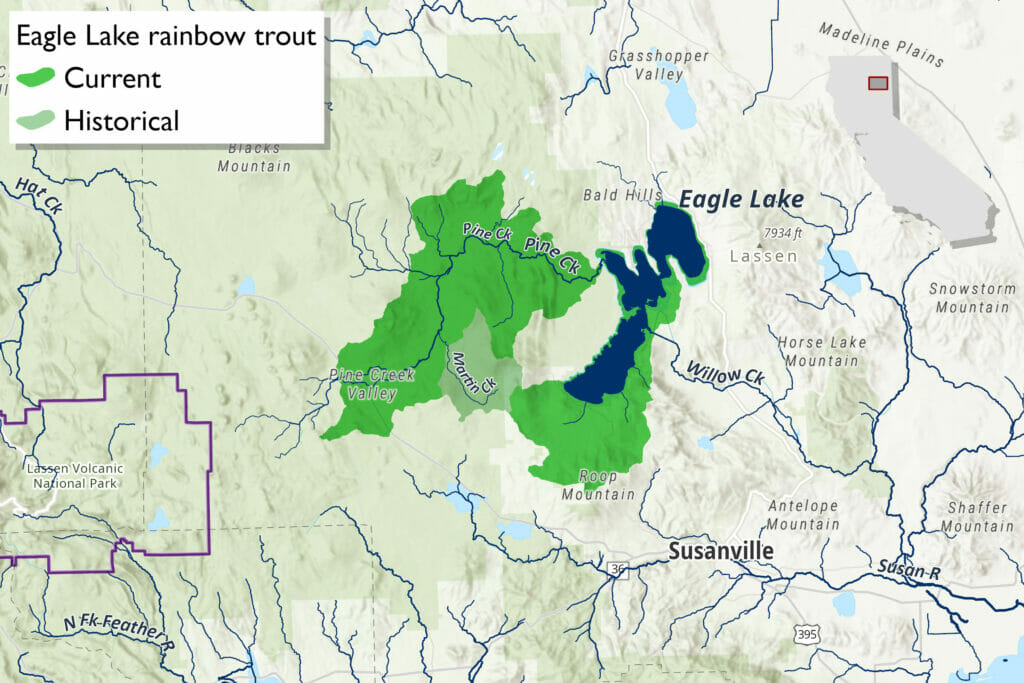

Not just any rainbow trout, though. Eagle Lake rainbow trout are a lake dwelling subspecies of rainbow trout found in Eagle Lake and its tributary streams on the east side of the Sierra Nevada.

Eagle Lake rainbow trout are uniquely adapted to the conditions in Eagle Lake, a 24,000-acre alkaline lake seasonally connected to its source tributaries only during the late spring snowmelt.

By the 1950s, overfishing and habitat degradation from logging, grazing and road development caused population declines so severe that the California Department of Fish and Wildlife initiated a hatchery program from the few remaining fish. In 2012, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service funded and built a fish ladder at the mouth of Pine Creek to allow passage of the native rainbows to historic spawning grounds. After years of being completely sustained by the hatchery, young Eagle Lake rainbow trout have been recently discovered in the headwaters of Pine Creek, providing hope that natural populations can once again flourish.

It was still quite early in the season and air and water temperatures were far too high for the lake to “turn” and for the baitfish food source for the rainbows to begin to swirl in the shallows where they are accessible by shore anglers.

So instead, I headed west, past Eagle Lake, to one of those watersheds in the Eagle Lake rainbows native watershed, within the Lassen National Forest. After passing the apocalyptic scorched-earth landscape left by the Goat Fire in 2007, I began to climb into the pine forests of Crater Mountain.

I quickly came to a large and very bright sign, clearly marked with a giant red X and the words “ENTRY TO NATIONAL FOREST CLOSED.” Thankfully, as I suspected or at least hoped, after getting out of the truck and reading the signage crudely stapled to the sign, I saw the closure listing, due to the Dixie Fire was outdated, ending only days before my arrival.

The nearly 10-mile dirt road to my destination resembled what some might call a shire, completely enclosed in overhanging pines so dark they blended with the black paint on my truck.

Arriving at the small alpine lake I had confirmed contained Eagle Lake rainbow trout and was within the Western Native Trout Initiative’s fish maps, I quickly realized I was by myself. Was it because of the signage which, to a less curious person, might indicate the entire forest was closed? Was it the Dixie Fire, reaching containment but still highly active only 15 to 20 miles to the northwest? Was the fishing so bad that no one found it worth their while to risk all the possible dangers?

As I parked the truck in the picturesque, yet seemingly abandoned lakefront campground, I saw a series of rise rings on the surface of the lake as fish rose to feed.

Now, I had to get out there, hundreds of yards from the rocky shoreline. After all, my research had only revealed that the California Department of Fish and Wildlife website very indiscriminately described the species found in the lake as “trout.”

In 2018, I had fallen head over heels for fly fishing through my passion for backcountry hikes and, specifically, obscure alpine lakes scattered about central Idaho.

At that point, for some reason, I believed a float tube was the single most essential tool to unlock my fly-fishing experience. So, bless her heart, in May of 2018, my mother, Christina Ritz, called my local fly shop and told them to hold one of their remaining Outcast Fish Cat Rise float tubes.

After picking up the float tube, I spent a number of sleepless nights dreaming of backpacking in, carrying my float tube, fins and tackle, and catching fish by myself.

Problem is, when I went to blow up the tube for a test run on local bass lakes and stocked ponds, I often would have frustrating fishing sessions. I’d snag the tube, or even worse, myself. I wouldn’t move any fish or I’d struggle to manage my equipment—hard enough on any given day let alone while afloat—in my lap.

Attempting redemption on the shores of the alpine lake, I backed my fin clad feet through the muddy edge, and kicked my way toward the drop-off.

I hammered the banks along the northern edge of the small lake, wind periodically pushing me around. I continued to chase rises as I heard them, sloppily casting my 10-foot, 4-weight, slightly longer and lighter than my go-to workhorse lake rod, toward the sounds.

A rise appeared directly ahead of my drift, driven by the soft wind at my back, not interrupted by my clumsy fin work. I presented a size 14 parachute Adams, possibly the most universal fly available on the market.

Nearly instantly, a splash erupted from the surface and the line went tight. The fish, whatever it was, made multiple runs and jumped two or three times, much like other rainbow species, as I reeled.

My heart raced as I saw that it was, in fact, an Eagle Lake rainbow. There was no doubt. It was obvious thanks to an almost pastel blue back. The last fish of my Western Native Trout Challenge was the very first fish I have ever caught in the float tube. My sweet mother could finally be proud.

After getting my fill that first afternoon, netting maybe a dozen Eagle Lake rainbows after driving almost 10 hours, I sat in awe of the lake water boiling in front of my camp.

Taking in the bubbling fish, steadily feeding off the surface of the lake, I noticed bright orange in the sky to the southwest, the general direction of the Dixie Fire, still burning only dozens of miles away.

The Eagle Lake rainbow trout currently swims in a precarious position as a species with a highly specialized and geographically restrained habitat range.

Trout Unlimited Restoration Project Manager Tiffanee Hutton serves as a member of the Pine Creek Coordinated Resources Management Planning Group. Formed in 1987, this stakeholder group was organized to build upon earlier restoration activities with the goal of reestablishing naturally reproducing populations of Eagle Lake rainbow trout.

While sustainable populations have not yet been successfully recorded, Hutton shared that she is proud of the growth she has seen in the project overall, and the growing population of Eagle Lake rainbows since her arrival.

For instance, since the 1980s when research was funded by the University of California-Davis, two distinct lineages of Eagle Lake rainbow trout have been identified. One form has inhabited the far upper portion of the primary tributary while another genetically identifiable species has habituated to the lower Pine Creek meadows and the lake.

Everything you wanted to know: Eagle Lake rainbow trout

Currently, due to year-round water flow as well as invasive brook trout in Eagle Lake, it is becoming harder and harder for this sub-species to reproduce sustainably.

However, Hutton has faith.

“Historically, for one reason or another, things have been relatively slow to move for the Eagle Lake rainbow trout and in Lassen County,” she explained. “But after a slow start, momentum is building, and funding is flowing for this species in the area.”

Hutton pointed out that, while each portion of the meadow landscape necessitates its own needs and ecological repair, recent studies, including acoustic tagging, show that work to restore fish passage throughout Pine Creek is empirically essential.

I spent the next day observing and fishing the perimeter of the lake for Eagle Lake rainbows. The wind came up early, discouraging further success from the float tube, so I made a lap of the small lake, occasionally hooking up with fish cruising the edges.

As the sun set, and the orange glow returned, I pondered the predicament of the Eagle Lake rainbow. Amidst one of the most beautiful scenes I had ever laid eyes on, a danger loomed just past the horizon, waiting to engulf the entirety of this species’ native waters.

With my Western Native Trout Challenge now complete, I sat on the tailgate of the truck and watched as the wildfire intensified sunset engulfed the lake.

Rings formed from the mouth of Eagle Lake rainbow trout continued to appear on the surface of the lake.

For the first time in a long time, I was content just to watch the rising fish on the surface. It gave me hope, seeing all of those happily feeding fish.

Like all of the native species I had experienced over the last five months, I hoped they were there when I returned, which I certainly will, to experience again.

This story, this series, is dedicated to my niece, Sloan Olympia Ryan. May all the bounties of California, of the West, be there for you to connect with when your time comes.