Life After Dams

Part 1 of a series. This week, we’re telling stories about what happens when dams come out and life flows back in. It’s a vision of what could be on the lower Snake: a free-flowing river and wild fisheries staging a remarkable comeback.

It is not always possible to restore wild places to their former ecological and aesthetic glory once human development has altered them. In some cases, however, the vitality of wild places can be recovered.

The Elwha River is one such place. Most of the Elwha is protected within the borders of Olympic National Park. But two dams built more than a century ago on the lower river to generate electricity prevented native salmon and steelhead from reaching most of their historic spawning and rearing habitat.

The need for power generated by these dams waned and alternative power sources became available. Tribal and conservation interests, including Trout Unlimited, went to work. After years of advocacy, Congress passed legislation authorizing removal of the Elwha dams and dedicating $360 million to pay for that and other river restoration actions, and for improvements to local community infrastructure.

Over four years, beginning in 2011, the Elwha dams were removed. The results have been incredible.

Wild summer-run steelhead, once prolific in the Elwha, were functionally extinct before the dams were removed.

That’s right, extinct.

But just six years after the dams came out, wild summer-run steelhead were back.

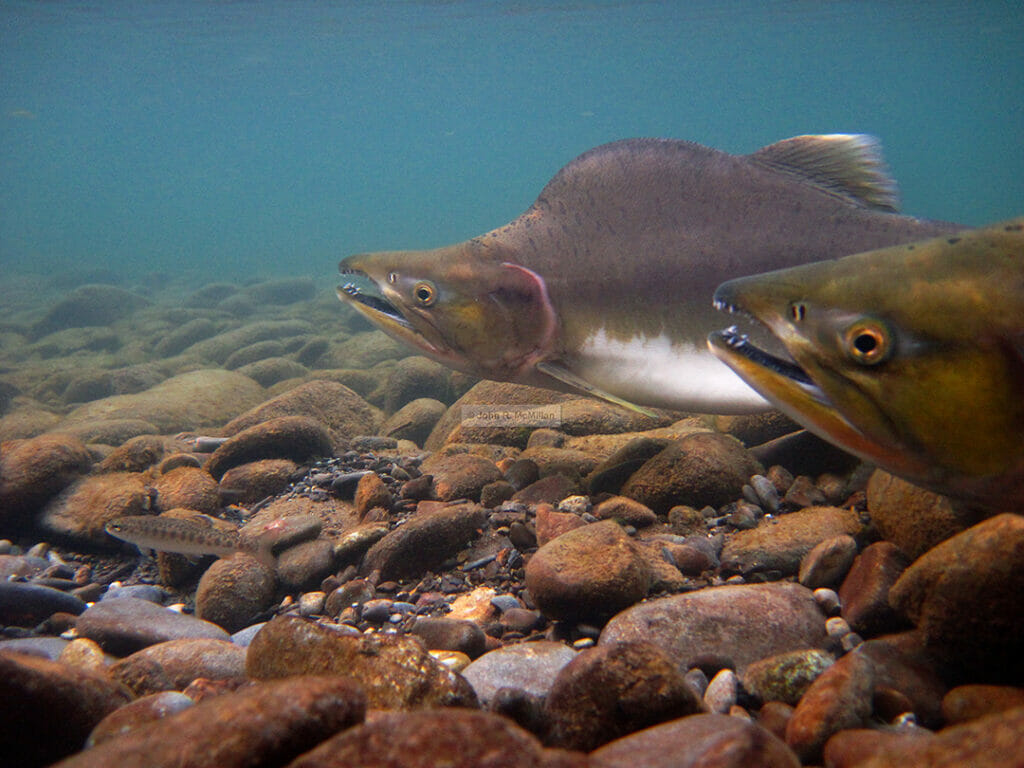

And not just a few. In one two-mile stretch of the river, a snorkel-survey team—including scientists with Trout Unlimited, state and federal resource agencies, and the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe—counted more than 100 adult wild summer-run steelhead. All told, the team tallied 341 summer-runs.

In all likelihood, these fish were derived from the rainbow trout population that persisted above the dams for a century. Thanks to their extraordinary life history profile, summer steelhead returned in force, like the Phoenix rising from the ashes.

No hatchery was used to produce these summer-runs. None was needed. All it took was unimpeded access from the ocean to the headwaters. And this resurgence happened despite poor ocean conditions that depressed other salmon and steelhead runs on the West Coast.

Rising from the Ashes, a film produced by noted filmmaker Shane Anderson for Wild Steelheaders United and Trout Unlimited, highlights the marvelous ability of nature to rebound quickly, if critical elements of an ecosystem are restored.

Not all species in the Elwha have responded as quickly to the removal of the dams as summer steelhead, but the overall trend is strongly positive. Salmon, steelhead and char are all now widely distributed throughout the basin and their numbers are increasing.

This can happen in other rivers, too, if we can adapt our thinking to the latest science and evolving economic and ecological conditions—and give steelhead and salmon room to do what they have done so well for millions of years.

Next up: Read Part 2 about dam removal on the Kennebec and Penobscot rivers in Maine.

Take out a dam, and life finds a way

Dams are ruinous to salmon, which are so finely adapted to their environment that to reproduce, they must return to the exact stream in which they were born.

But dams don’t live forever.

Sometimes they become so outdated that the cost of maintaining them—including biological and cultural costs—exceeds the cost of taking them out.

When we remove dams, we see clear results: a healthier river ecology, and trout, salmon and steelhead moving back into their historic habitats upstream. No other restoration action comes close in terms of helping migratory freshwater fish species reach spawning waters and rebuild their populations.

It’s that simple. Take out a dam, and life finds a way.