Data collected, scientists now set out to gauge how flows affect the river’s wild browns

For the past two-plus years, TU’s Deerfield River Watershed Chapter members and community volunteers have been tracking the movements of 30 brown trout carrying surgically implanted radio transmitters.

Now, after putting thousands of miles on their cars to collect 24 million GPS data points, the chapter in northwestern Massachusetts is wrapping up an important phase of its ambitious study.

This 17-mile stretch of the 70-mile Deerfield River is controlled by Brookfield Power’s Fife Brook Dam and Bear Swamp Pump Storage Facilities hydro-electric operation. A well-known and popular trout fishery, it was recently selected as one of our Priority Waters—places around the country where TU can make the greatest contribution to the health, resiliency, and viability of trout and salmon fisheries.

The collected brown trout telemetry data are being analyzed by the chapter’s partners at the USGS Eastern Ecological Science Center, part of the Silvio O. Conte Research Laboratory in Turners Falls, Mass.

The USGS biologists are studying the data to determine if there are impacts on tagged trout from daily hydro-peaking flows, which fluctuate from high levels during power generation to low levels when generation is not occurring.

“We’re looking to determine whether hydro-peaking affects the movement of adult brown trout throughout the year, and especially if the hydro-peaking interferes with spawning,” said Matthew O’Donnell, research ecologist with the USGS Conte Lab, who has been working with the chapter on this project.

Complete analysis of the data will take at least a year.

Field surveys during an earlier spawning study by the chapter turned up some trout redds that were small and sometimes even somewhat misshapen. None of these odd-looking redds produced any trout eggs. This left us wondering if these particular redds were unfinished and abandoned.

The suspicion was that spawning trout were being pushed off the redds as water suddenly receded as a result of reduction in flows controlled by the dam. Chapter members hope the study will answer this question.

A preliminary assessment of the 24 million lines of data has already suggested that most of the brown trout did not move far from the area where they were first captured, fitted with a transmitter, and released.

“A few moved about a kilometer,” O’Donnell said. “And one traveled up the Cold River (a tributary), and I think it’s still up there. But most tagged fish really didn’t move around much.”

Every brown trout in the study had to be at least fifteen inches long and weigh one pound or more in order to safely accommodate the transmitter and battery.

O’Donnell noted that he and his colleagues will be searching through the data for indications of even the slightest movements made by the tagged brown trout, especially when they are around the redds.

Time-based detections of trout mobility can be correlated with flow levels and water temperatures. USGS and DRWTU placed temperature and flow loggers near the trout redds to understand the role these factors play in trout behavior.

“An in-depth analysis of all this data should tell us a lot more about the potential impacts hydro-peaking has on trout,” O’Donnell added. “If there is an impact on brown trout movement, correlated to peaking flows, hopefully understanding the impact could lead to better management decisions in the Deerfield and other large river systems with altered flow regimes.”

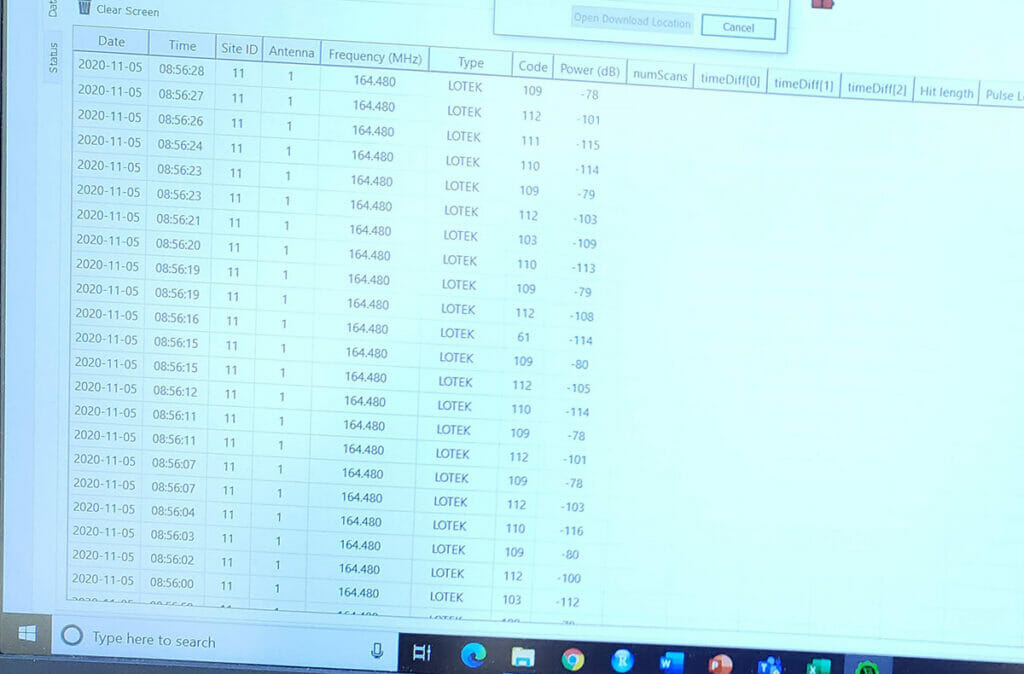

To gather the data, TU volunteers drove along the river with mobile receivers. In addition, three solar-powered fixed receiver stations were erected near known spawning areas. These receivers recorded signals from the transmitters in the tagged browns 24 hours a day for about two years. This assembly collected the bulk of the 24 million data points.

Eric Halloran, now president of the DRWTU chapter, also developed his own system using a telemetry receiver attached to a hand-held Yagi antenna to pinpoint the location of individual fish.

These data are being used for quality control with the mobile data and were helpful in determining whether an individual fish was alive or dead.

For example, if O’Donnell noticed that a particular fish had barely moved its position from the previous month, he would alert Halloran.

Using his handheld receiver, a compass, and a Garmin GPS, Halloran, along with chapter volunteers, would triangulate the position of that individual fish. By calling out the bearings and signal strengths from various points along the shore, the team produced hand-written and voice recordings of the data. Later, Halloran transcribed and charted the results.

By reviewing the variability of signal strengths and charted positions from the data, inferences could be made about the status of the fish.

Only three tagged fish were known to have perished during this multi-year study.

O’Donnell and his colleagues will be analyzing the data points over the next year. He described the project as “massive” and is excited about what the data could reveal about the impact of daily hydropeaking on the Deerfield’s brown trout population.

“This is a really big project and there was no way we could gather all this data without Deerfield TU,” O’Donnell said. “We don’t have the personnel or the budget. It’s really been a fantastic partnership.”

Michael Vito is the past president of the Deerfield River Watershed Trout Unlimited Chapter. He works in communications and government relations. He has been a daily newspaper reporter and was a senior staffer to a former U.S. Senator, and chief aide to a former Massachusetts Mayor. He lives in Florence, Massachusetts with his wife Anne, and their dog Daisy.