Removing the four lower dams on Maine’s Kennebec River may be the best hope to save Atlantic salmon in the U.S.

Spring was a time of renewal and reward in Maine in the pre-industrial age. Hardened by tough winters, residents relished the arrival of warm weather and, even more importantly, nature’s bounty that came with it.

The majestic Kennebec River was the center of the excitement for those who lived nearby, a group that included Indigenous peoples and later European settlers who relied upon the land and water for sustenance.

Each spring the river would fill with migrating fish, from small alewives and American shad to massive Atlantic sturgeon. The Atlantic salmon was arguably the king of the Kennebec, with runs thought to top 100,000 fish in some years in the early 1800s. Those fish were critical from not only a nutritional standpoint, but also a cultural one.

Today, Atlantic salmon continue to return to the Kennebec River. But the numbers are a fraction of what they were. In 2018, just 11 adult Atlantic salmon were collected at Lockwood Dam, the lowermost barrier on the river.

ELEVEN!

The average return over the past decade is just 35 salmon annually. Atlantic salmon in the Gulf of Maine region have been federally listed as endangered.

“We’ve seen in other rivers what ultimately happens when salmon are put on this sort of downward trajectory, and we must avoid that fate on the Kennebec,” said Keith Curley, Trout Unlimited’s vice president for Eastern Conservation. “Salmon runs on the Kennebec can recover – the upstream habitat is there – but not with four dams in the way.”

While the river’s salmon and other migratory fish have faced many challenges, from polluted water to warming oceans, none have been as damaging as a series of aging hydro dams that have kept sea-run fish from reaching important spawning grounds. Those dams remain the most significant obstacle to recovery of fish populations. Without extraordinary human effort, the river’s salmon would almost certainly already be extinct. As it is, they are on the brink.

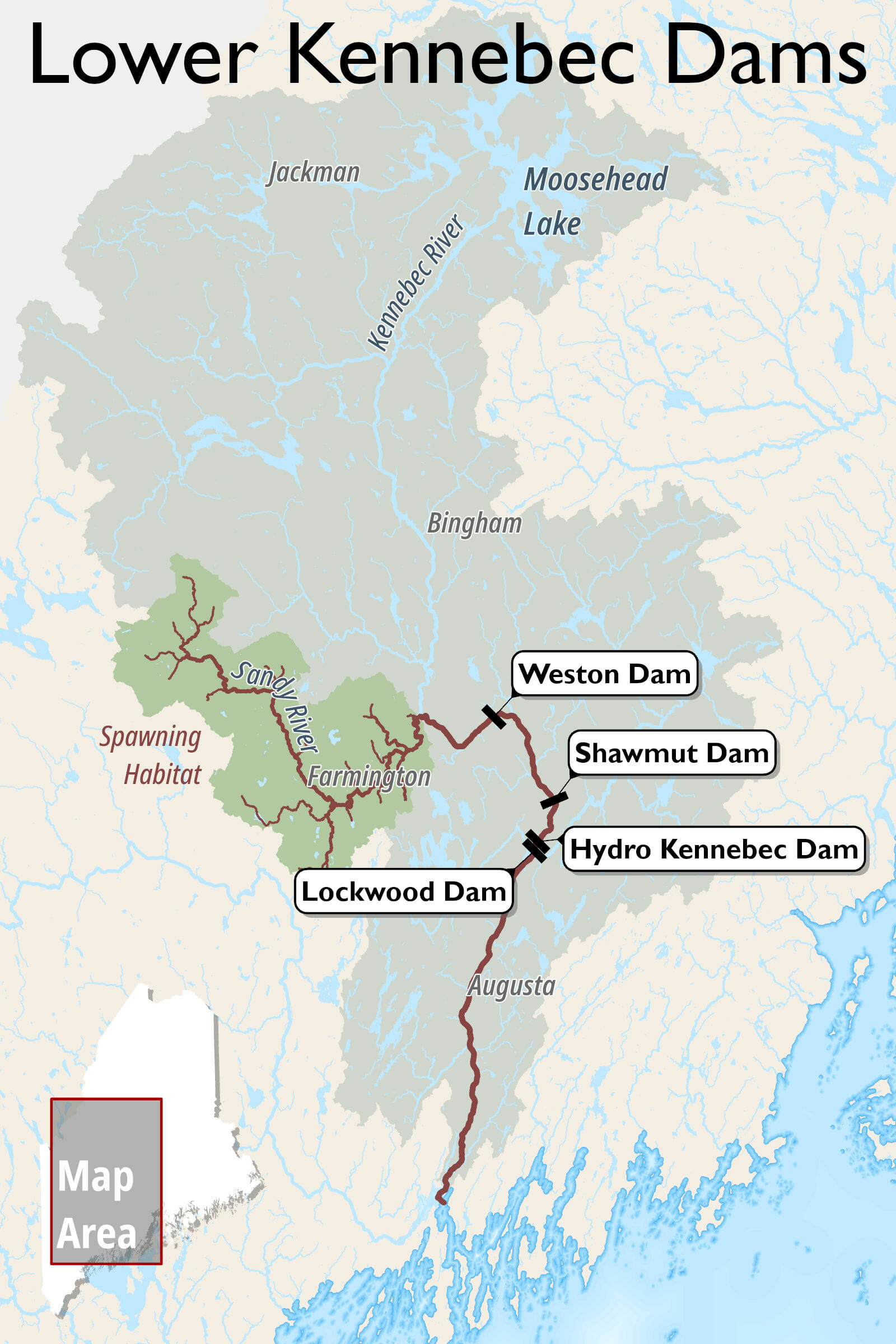

Advocates for salmon recovery say the only viable way to save Atlantic salmon in the Kennebec River is to remove the four lowermost barriers on the river, which would allow the fish to reach the best spawning habitat in the system in the Sandy River.

“The Kennebec is a resource of global significance” said Nick Bennett, a scientist with the Natural Resources Council of Maine. “It deserves the same level of national attention and action as the Klamath.”

The third upstream dam on the Kennebec, the Shawmut dam near Fairfield, is currently under review by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, a process that requires FERC to consider the dam’s ecological impact. Supporters of the river’s restoration say the timing is ideal to decommission and remove that dam and the three others, and that returning the lower Kennebec to its free-flowing state is the only reasonable way to revive runs of salmon and to save the iconic fish from extinction in U.S. waters.

A coalition of salmon advocates — the Natural Resources Council of Maine, Maine Rivers, the Conservation Law Foundation and the Atlantic Salmon Federation — have sued Brookfield, the international energy giant and owners of the Shawmut dam, asserting that the company is breaking the law because it is operating the dams without a “take permit,” which is required under the Endangered Species Act when operations directly impact mortality of listed species. The suit is pending.

Bennett said the future of the iconic fish in the U.S. rests on restoration efforts in the Kennebec River. “If we don’t save Atlantic salmon in the Kennebec,” Bennett said, “we’re going to lose them entirely in this country.”

A typical history

Like so many American rivers, the Kennebec has been victimized by progress, its waters polluted and dammed to the point of near-catastrophic ecological damage. Timber-harvesting operations utilized rivers for massive, habitat-damaging log drives. As the industrial revolution progressed, factories that lined streams and rivers used them as dumping grounds for all manner of waste.

In 1839, as the industrial revolution was just beginning, Henry David Thoreau spent several days paddling the Merrimack River, a northeast river that, like the Kennebec, eventually flows into the Gulf of Maine. John Waldman, a professor at New York’s Queens College who is an expert in river health, said Thoreau’s book about the trip made clear his feelings.

“He foresaw doom,” Waldman said.

And he was right.

“For Atlantic salmon, the habitat alteration and associated impacts proved too much, with 10 individuals or less returning to the river in each of the last five years,” reported the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in a 2021 story.

On the Kennebec, arguably nothing has been as cumulatively destructive to the river’s migratory fish as dams.

The first of those, Edwards Dam, was constructed nearly two centuries ago just above tidal influence. Although the 1837 structure included a fish passageway, the passage was damaged beyond functionality just two years into the dam’s life. Blocked from spawning grounds, the river’s populations of anadromous and diadromous fish cratered.

NOAA reports that even with intense restoration programs, the most recent peak for returning adult Atlantic salmon coastwide was in 1985 at just 5,000. Salmon once returned to scores of rivers in the Northeast, but now come back to fewer than a dozen rivers in Maine. The current number of returning salmon is thought to be about 1,000.

The four lowermost dams on the Kennebec are not critical to the state’s power grid.

Cumulatively, the Lockwood Dam, Hydro-Kennebec Dam, Shawmut Dam and Weston Dam have just 45 megawatts of capacity, only 6 percent of hydroelectric capacity in Maine. Increases in capacity of other forms of renewable energy, including Maine’s booming solar segment, have mostly rendered moot the benefits of the four lower Kennebec dams to the state’s power grid.

Striving to save salmon

Just as man’s action had impacted fish populations on the river, it has taken human intervention to try to save those fish.

These efforts border on the heroic, and include the creation of redds using fertilized eggs collected at hatcheries, a smolt-stocking program below Lockwood Dam, and a trap and transfer program in which salmon collected below Lockwood Dam are trucked 50 miles to spawning habitat in the Sandy River that is blocked by the four dams

One report succinctly lays out the key to salmon recovery: getting fish to spawning grounds.

“Achieving the Atlantic Sea-Run Commission’s long-term restoration goal for the Kennebec River is dependent upon the availability of adequate fish passage to areas of suitable habitat,” reads one report from commission biologist Kenneth Beland.

The year that report was produced? 1986.

Since the report was published nearly 40 years ago removal of the Edwards Dam has been the only considerable progress toward improving fish passage.

NOAA scientists have studied the impact of dams on smolt out-migration success. Between 2005 and 2013, NOAA implanted radio tags in 941 salmon smolts in the Penobscot system. The study found that even if smolts made it through dams, each dam they had to pass through increased their risk of mortality in the estuary by 6 to 7 percent.

Applying those number to the Kennebec, for every 1,000 smolts that make it through the four dams between the Sandy River and Merrymeeting Bay, 240 to 280 of those fish will never make it from the estuary to the open ocean, where the threats only escalate.

“The life cycle of a salmon is difficult, so increasing mortality, particularly with a population already on the brink of extinction, could push the population beyond the point of no return,” said Landis Hudson, executive director of the nonprofit Maine Rivers.

It’s not too late

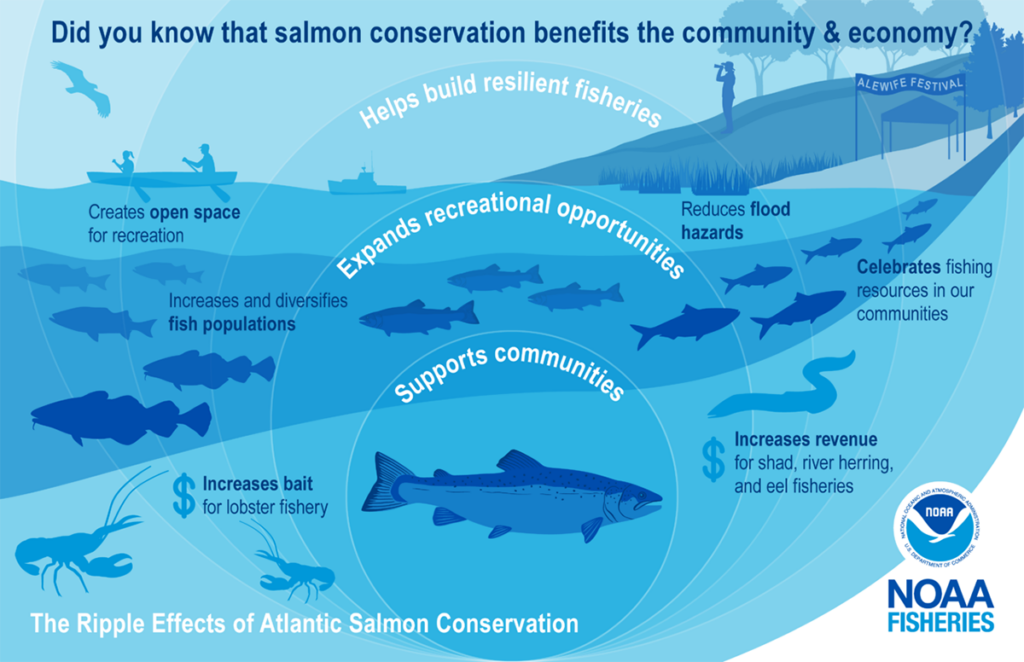

The Edwards Dam was breached in 1999 after federal officials declared that the dam’s existence imperiled sea-run fish. Since the dam came down the river below the Lockwood Dam has come back to life. For example, in an average year, more than 3 million river herring flood up the Kennebec to spawn in the Sebasticook River, a tributary that enters not far below Lockwood dam. Shortnosed and Atlantic sturgeon can be seen jumping in the free-flowing waters where the dam once stood. Bald eagles swarm the river to feast on herring and shad. Fish-chasing seals have been spotted miles upriver.

“The river below the Lockwood Dam is what a healthy Kennebec can look like,” said Jeff Reardon, who headed Trout Unlimited’s efforts to remove dams on the Penobscot River and who now works on salmon restoration for the Atlantic Salmon Federation. “Migrating fish are such an important part of the ecosystem. When they return, they bring with them all the other species that rely on them.”

NOAA is expected to release a biological opinion, or BiOp, in mid-February, triggering the next step of reviews through the FERC relicensing process for Shawmut Dam. The agency’s assessment of the challenges facing Atlantic salmon is blunt, and the first major action listed as part of NOAA’s recovery plan is to “improve connections between ocean and freshwater habitats important for salmon recovery.”

Bennett at NRCM says that because retrofitting old dams with fish passage infrastructure has proven to be ineffective for salmon recovery; the only way to save salmon in the Kennebec is to remove the four lower dams.

“We don’t need these four dams,” Bennett said. “They’re not worth the destruction that they cause to what used to be Maine’s greatest river in terms of sea run fisheries production and that use to have one the largest runs of Atlantic salmon in the United States.”