Atlantic salmon runs in U.S. waters have endured blow after blow over the past two centuries. They just received another one.

The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) this week released a Biological Opinion (BiOp) on an energy giant’s proposed solutions to improve fish passage infrastructure at four hydroelectric dams on Maine’s Kennebec River, one of just a handful of rivers in the U.S. to support runs of Atlantic salmon.

The BiOp suggests that dam owner Brookfield Renewable Energy’s proposals “may adversely affect but are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of Gulf of Maine distinct population segment of Atlantic salmon, shortnose sturgeon, or the Gulf of Maine distinct population segment of Atlantic sturgeon.”

Advocates for salmon restoration expressed disappointment, frustration, anger and sadness at the contents of the 325-page document.

In a press release, the Kennebec Coalition and Conservation Law Foundation said the NOAA decision “ignores reality.”

“Brookfield’s four dams on the Kennebec are pushing Atlantic salmon to the brink of extinction and blocking restoration of other sea-run fish critical to the health of the Gulf of Maine,” the groups said. “It is disturbing that NOAA appears to be disregarding science and blindly trusting Brookfield with the future of Atlantic salmon and other species that depend on a healthy river.

“Removal of these dams provides the best chance to prevent Atlantic salmon from becoming extinct in U.S. waters while also continuing the restoration of a vibrant, healthy Kennebec River.”

The Kennebec Coalition includes the Atlantic Salmon Federation, Maine Rivers, Natural Resources Council of Maine (NRCM) and Trout Unlimited, including TU’s Kennebec Valley chapter. Along with the Conservation Law Foundation, the Coalition works together to advocate for the restoration of the Kennebec River.

Prior to the industrial era, an estimated 100,000 Atlantic salmon returned annually to the Kennebec, the runs critical to the survival and cultures of the region’s indigenous populations and European settlers alike.

Dammed heavily starting in the early 1800s, the river soon saw populations of migratory fish crash.

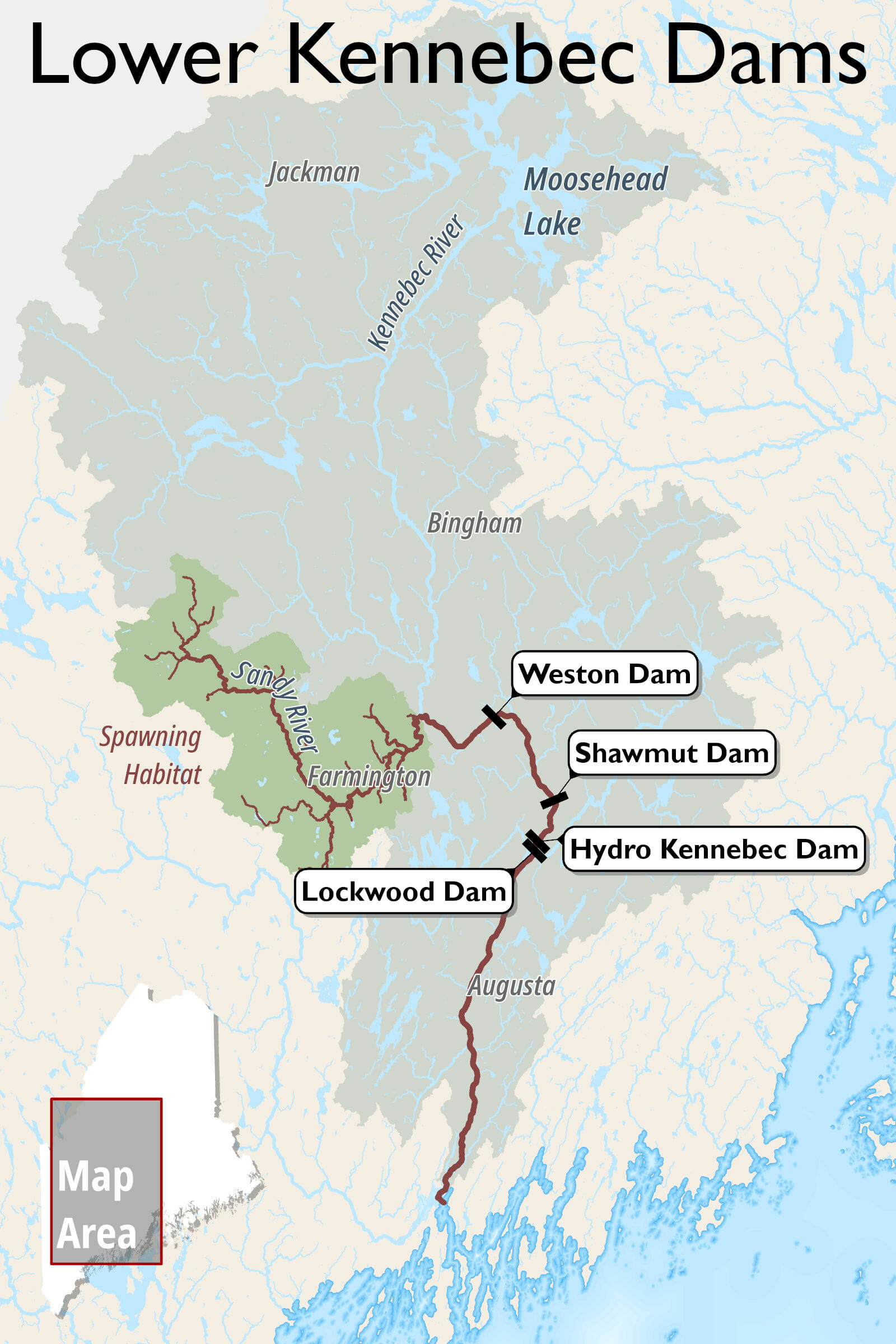

Today, just a few dozen wild salmon return annually to the river. They are trapped at a fish lift at Lockwood Dam, the lowermost barrier on the river, and trucked to spawning habitat in the Sandy River, a Kennebec tributary. Juvenile salmon from the Sandy must pass through a total of four dams once they reach the Kennebec on their return journey to the Gulf of Maine. A treacherous journey both upstream and downstream for Atlantic salmon adults and juveniles.

Brookfield proposes constructing a new fishway at Lockwood Dam, as well as fish lifts at Shawmut and Weston dams, which currently offer no upstream passage. The Canada-based energy conglomerate is also proposing actions to improve downstream passage of juvenile salmon, including installing booms to guide the young salmon away from turbine outlets toward safer dam-passage areas.

Salmon advocates point to data they say proves that similar fish passage infrastructure at dams is not effective at passing the number of salmon — and other fish species upon which the recovery of salmon is dependent — required to restore salmon populations that are already on the brink.

For example, NRCM recently obtained documents through an open records request that show that the fish lift at Brookfield-owned Milford Dam on Maine’s Penobscot River is not meeting fish passage standards set in agreement based on the Endangered Species Act.

“The so-called solutions Brookfield is proposing haven’t worked elsewhere,” said Landis Hudson, executive director of Maine Rivers. “So how could NOAA believe they will work on the Kennebec?”

The BiOp was produced as part of the process of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s (FERC) ongoing process to relicense the Shawmut Dam, the third upstream dam on the Kennebec River.

In September 2021, the Atlantic Salmon Federation, Conservation Law Foundation, Maine Rivers and the NRCM sued Brookfield in federal court, asserting that the company is violating the Endangered Species Act. The company’s license allowing it to kill and injure a certain number of salmon as part of its operations expired in 2019. The company has continued to operate the dams without a so-called “take” license since.

“Brookfield is a company that touts its dedication to environmentally friendly energy production,” said Nick Bennett, a scientist with the NRCM. “Yet they continue to operate these dams knowing full well that they don’t and can’t facilitate effective fish passage. It defies logic.”

Nearly 800 Trout Unlimited members and supporters recently signed a letter to NOAA urging the agency to find that Brookfield’s proposals for fish passage at the four lower Kennebec dams are insufficient.

“Obviously we’re disappointed with NOAA’s failure to consider the science and facts that we and other salmon advocates have plainly laid out in court and in other venues over the past decade,” said Kirt Mayland, who is heading Trout Unlimited’s Kennebec River advocacy efforts. “The BiOp paints an unrealistically optimistic picture of Brookfield’s fish passage proposals. If they haven’t worked elsewhere, why would they work here?”

Once a BiOp is released it cannot be altered. That leaves those fighting for the recovery of Maine’s dwindling salmon runs to continue their efforts through the FERC relicensing process.

“We aren’t giving up,” Bennett said. “We know that the longer this process draws out, the greater the likelihood that we lose wild Atlantic salmon in this country.

“But we are still trying to be optimistic that eventually Brookfield will want to work with us to ensure that doesn’t happen. It would not be a good legacy for them to have played such a key role in the disappearance of this iconic species.”