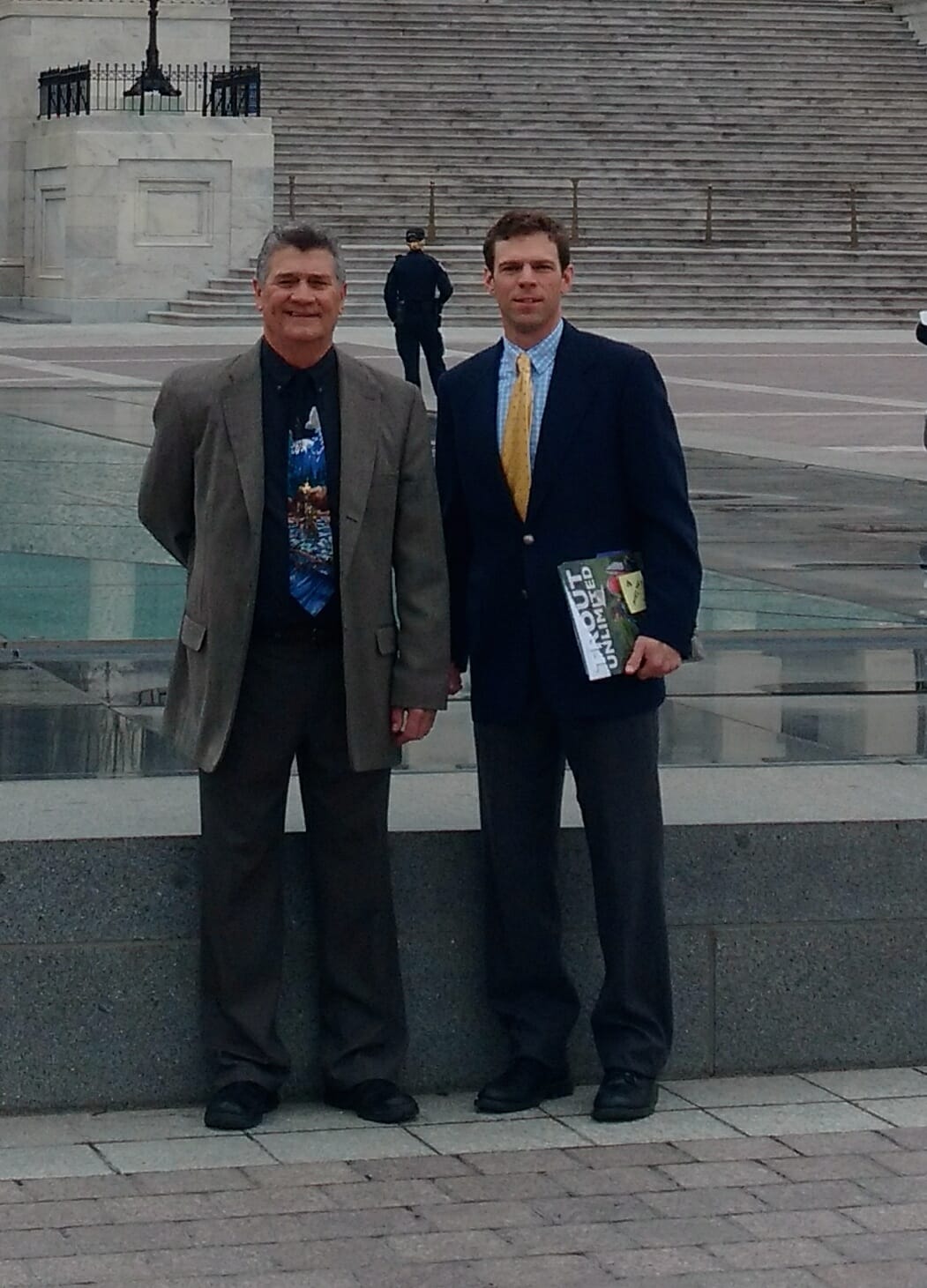

Raymond Phares (left) of Circleville, W.Va., traveled to Washington DC in late March to meet with Congressional offices in support of funding for the Chesapeake Bay Program. He was accompanied by Trout Unlimited’s Dustin Wichterman, who oversee’s TU’s restoration efforts in the up

per Potomac watershed.

By Mark Taylor

Trout Unlimited staffers and volunteers converged on Capitol Hill the week of March 20, visiting with lawmakers and their staffs to urge funding support for TU’s efforts in the massive Chesapeake Bay watershed.

The event had been on the calendar for a while, but it took on additional urgency with the release the previous week of the Trump Administration’s FY 2018 budget blueprint. That plan proposes a significant cut to funding for the Environmental Protection Agency, including total elimination of the Chesapeake Bay Program.

Elimination of that $73 million program would severely limit the amount of coldwater habitat conservation TU can accomplish and stall progress on Bay cleanup efforts.

The Chesapeake Bay Program’s Small Watershed Grants program has enabled TU to work with farmers in Virginia and West Virginia to improve their farming operations while simultaneously improving trout habitat on their lands. In Pennsylvania, grants have helped local communities restore trout streams, which helps downstream by contributing cold, clean water to the Chesapeake Bay.

It’s the proverbial win-win situation.

alt=”” title=”” />Virginia landowner Jerry Black (left) visited Congressional offices with TU’s Seth Coffman to tout the importance of the Chesapeake Bay Program in stream restoration in Rockingham County.

alt=”” title=”” />Virginia landowner Jerry Black (left) visited Congressional offices with TU’s Seth Coffman to tout the importance of the Chesapeake Bay Program in stream restoration in Rockingham County.

Virginian Jerry Black is one of those landowners who has partnered with TU, working to improve habitat on Beaver Creek in Rockingham County. Part of the North River watershed near Harrisonburg, Beaver Creek is a spring-fed creek and popular fishing stream that is seeing a return of native brook trout since restoration work began.

Black, along with TU’s Seth Coffman, who oversees restoration efforts in the Shenandoah and James River watersheds, spent the day meeting with the offices of Virginia legislators Representative Bob Goodlatte, and Senators Tim Kaine and Mark Warner.

“The restoration of Beaver Creek has been a real benefit to the community,” Black said. “Anglers come from all over the region to fish it.

“Also, the restoration projects TU has completed allow our local chapter and Project Healing Waters volunteers to get more wounded veterans on the water fishing.”

Landowner Raymond Phares of West Virginia visited with the offices of Representatives Evan Jenkins and Alex Mooney, and Senators Shelley Moore Capito and Joe Manchin. TU’s Dustin Wichterman, who oversees TU’s protection and restoration efforts in the upper Potomac River watershed, accompanied him.

Phares is a native West Virginian whose family has worked the land for 200 years, and who recognizes the value of stream restoration. He also owns an excavation business, which has helped him connect with other landowners whose property can benefit from stream restoration work.

“I really believe the farmers in this area are good stewards of the land and know that stream restoration projects help people both up and downstream,” said Phares, whose business is in Pendleton County. “It makes sense as part of preventing erosion and farm damage as much as it does to keep our waters clean and of high quality.”

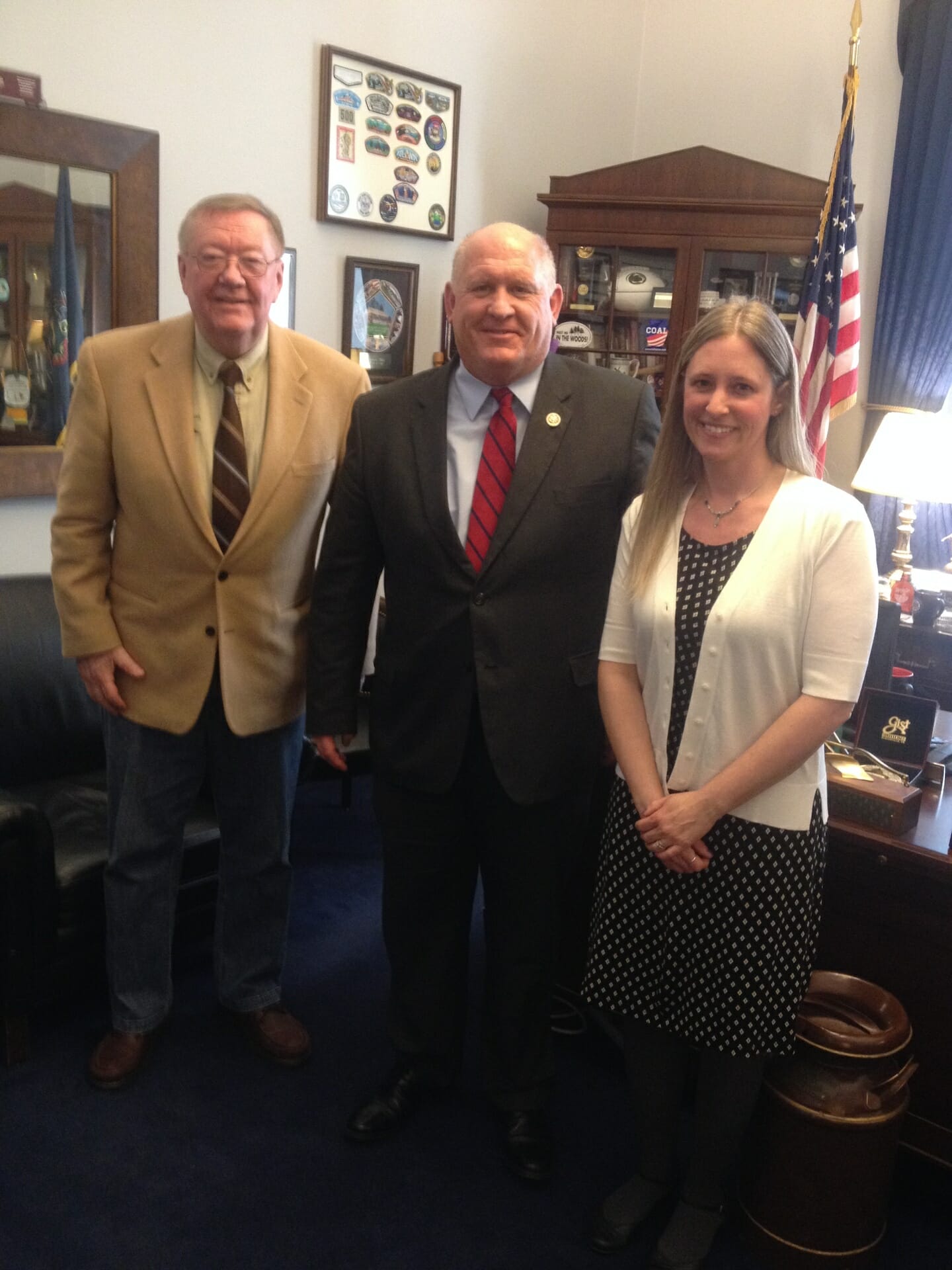

alt=”” title=”” />Glenn “GT” Thompson, R-Pa., (center) took time to meet with constituent Dick Sodergren (left) and TU staffer Amy Wolfe.

alt=”” title=”” />Glenn “GT” Thompson, R-Pa., (center) took time to meet with constituent Dick Sodergren (left) and TU staffer Amy Wolfe.

Landowner Dick Sodergren traveled to the Capitol from Pennsylvania, and was accompanied by Amy Wolfe, who directs TU’s Pennsylvania Coldwater Habitat Restoration and Eastern Abandoned Mines programs. The pair met with offices of Senators Bob Casey and Pat Toomey, and Representatives Glenn Thompson and Matt Cartwright.

Sodergren is the president of the Kettle Creek Watershed Association, a group that has been a key partner with TU in restoration efforts in that area in Clinton, Tioga and Potter counties for two decades.

“Grants from the Chesapeake Bay Program are turned into local jobs,” Sodergren said. “We use the grants to hire the technical experts and local contractors, and to purchase the materials we need.

“All these people pay taxes and add to our local economy.”

Hundreds of thousands of rivers and streams comprise the Chesapeake Bay watershed, which has a footprint that covers 64,000 square miles. In their upper reaches, many of those rivers and streams hold trout, including brook trout, the only trout native to the East.

Yet much of that brook trout habitat is degraded, and the fish now are found in only a small percentage of the streams where they once existed.

Those trout help indicate the health of those watersheds, and that’s important for people, too. The rivers and streams in the Chesapeake Bay watershed provide drinking water for more than 13 million people from six states and Washington DC.

And there is the bay itself, which has an economic worth estimated at over $1 trillion. The Bay’s environmental challenges, which directly impact the important seafood, recreational fishing and tourism industries, are well documented. So is the progress that has been made in recent years — progress largely due to the Chesapeake Bay Program.

In addition to its in-person efforts on Capitol Hill, Trout Unlimited is urging its members and supporters to stand up for the Chesapeake Bay Program by contacting their elected officials and President Trump. TU’s Advocacy Center offers summaries of this and other TU campaigns.