Southern steelhead country.

My son and I wandered into the land of the southern steelhead yesterday. Cactus sprouted like gargoyles from the sandstone outcroppings that lined the creek up which we hiked.

This winter has been profligate all across California and yet another massive cumulonimbus cloud reared up over the peaks above us. Then it rained, hailed and snowed, in that order. We were cold and sodden by the time we got back to the car.

We didn’t see any steelhead. But amazingly enough, there are steelhead genes in resident O. mykiss in the upper reaches of that watershed.

This area is basically a desert. Surface water is often rare and fleeting here. Yesterday, however, the creek roiled with filmy, lime-green water.

This creek doesn’t have water in it most of the year. In very dry years it may never have water in it. But it turns out such waters are often utilized by fish when they do connect to other reaches and allow access to the new habitat. This is true throughout the historic range of North American steelhead.

This creek we hiked, passing piles of black bear scat, is a feeder stream to Sespe Creek, a primary tributary to the Santa Clara River. The Santa Clara drains the Topatopa mountain range near the California beach town of Ventura and once hosted a robust run of the southern California coastal steelhead, now once of the state’s rarest native fishes.

A paltry 500 adult southern steelhead are thought to return nowadays to coastal streams in the 300 miles of coastline between Point Conception and the Mexican border. The Santa Clara is a priority watershed for southern steelhead restoration under the federal recovery plan for this distinct population segment.

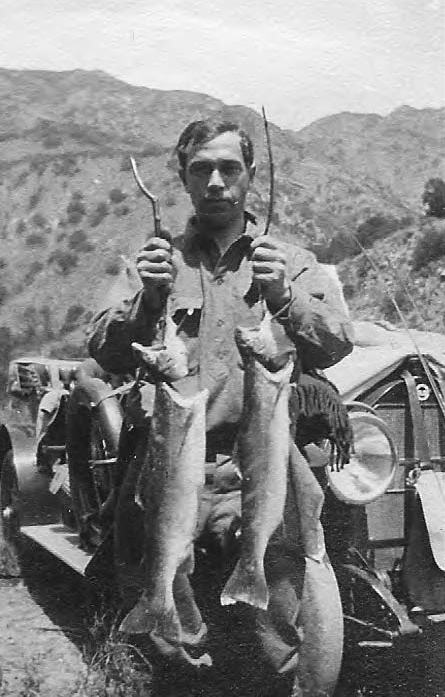

(L) Steelhead caught in Sespe Creek, 1911.

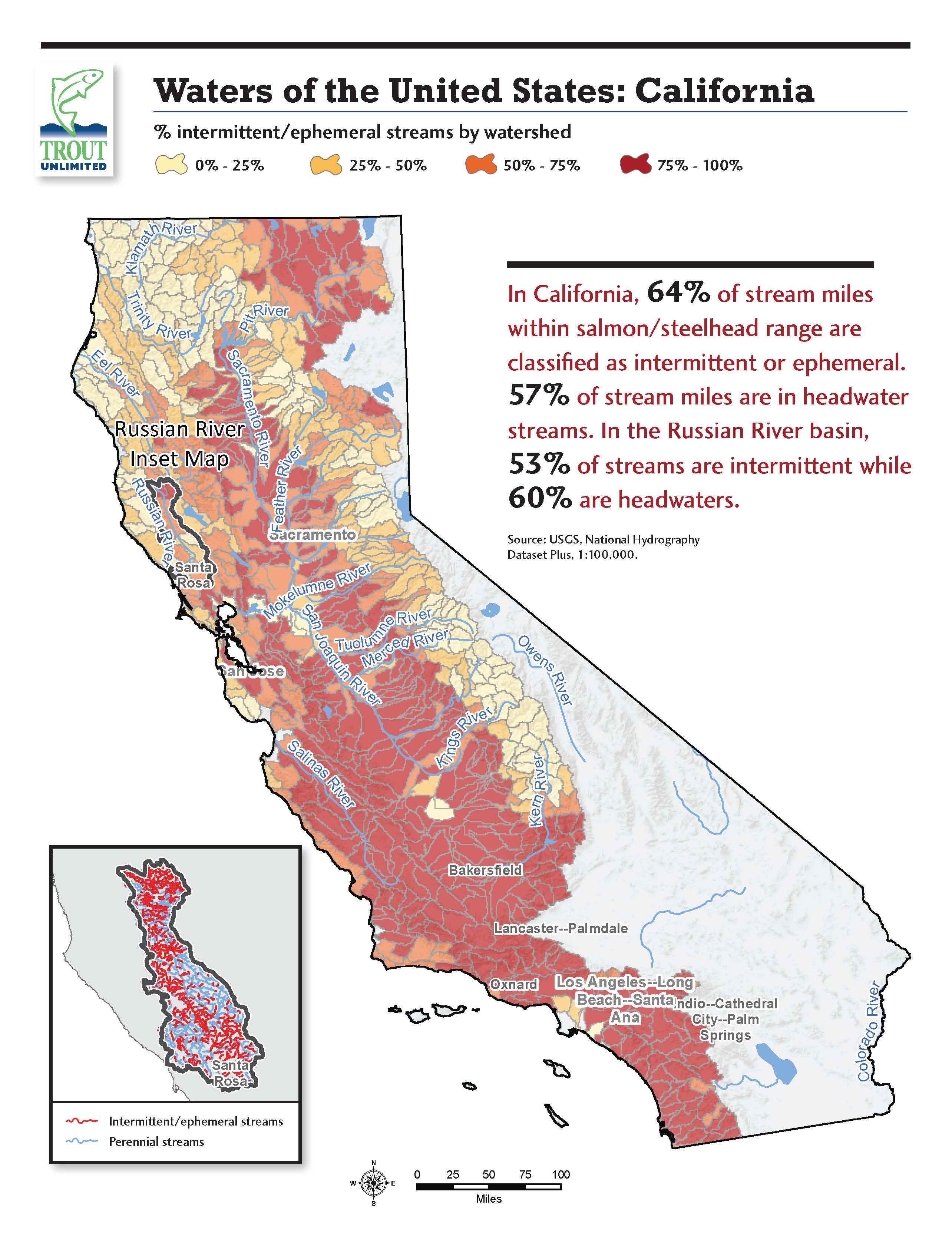

It seems counterintuitive that stream segments that only flow seasonally (“intermittent streams”) or after major storm events (“ephemeral streams”) would be important for salmonids. But across the U.S. two-thirds of all stream miles fall into this category of waterway. And it’s not just steelhead that rely on these habitats-so do Coho and Chinook salmon, coastal cutthroat, and resident rainbow trout.

Most everyone knows that salmonids are diva-like in their habitat preferences. Trout and salmon require cold, clean water and have a narrow range of tolerance for temperature and water quality. For some portions of the year, in many watersheds, intermittent and ephemeral streams provide the requisite conditions for them, especially for spawning and rearing.

I thought about this as we hiked up the narrow canyon, crossing and recrossing the streambed by hopping on tawny boulders. Trout and salmon are the ultimate opportunists. Steelhead, in particular, exemplify this trait-they have the greatest life history diversity of any of the family Salmonidae and thus can thrive in both deserts and rainforests.

Diversity translates to resilience to environmental stressors. And, if we are to rebuild runs of wild steelhead, the great freshwater sportfish of the western edge of this continent, and keep alive our opportunity to fish for them, it is this diversity that will carry the day.

It also seems counterintuitive that the federal law intended to protect water quality-the landmark Clean Water Act, passed in 1972-would not apply to streams like the one my son and I hiked. After all, water flows downhill. You can’t ensure good water quality in a river’s mainstem in you allow pollution in its tributaries.

But that’s what could happen under a current proposal from the Trump administration.

(R) A lot of trout and salmon habitat in California is classified as intermittent or ephemeral.

For nearly thirty years the Clean Water Act was interpreted to apply to virtually all water bodies in the United States, including wetlands and seasonal creeks that may be disconnected at times from perennial flowing streams. But two Supreme Court decisions, in 2000 and 2006, suggested there could be limits to that interpretation.

These decisions left a lot of stakeholders, industries and communities in a sort of water quality limbo, particularly since not all states have their own water quality statutes. The Obama administration took on the challenge of clarifying what is and is not covered under the Clean Water Act.

After an exhaustive process grounded in the best available science and incorporating feedback from more than one million public comments, the Clean Water Rule was published in 2015. It clarified that intermittent and ephemeral streams and wetlands are protected for water quality under of the Clean Water Act. The Rule also affirmed that the Clean Water Act does not apply to most normal farming and ranching operations.

But the Rule, despite its careful consideration of some of the implications of the law and clarification of agricultural exemptions, was nonetheless criticized by some as government overreach, and then-candidate for President Trump pledged to overturn it.

Which the president is now trying to do, through a rewrite of the Clean Water Rule that removes the water quality protections for basically any water body that ever may be disconnected by surface flow from a mainstem river or stream.

Hank Patterson says don’t take clean water for granted.

The public can comment on the proposed rewrite of the Rule until April 15. Go here to do so.

Fortunately for those of us who have an unabashed crush on native trout and steelhead, California has a strong state water quality law that protects places like the small headwaters of the Santa Clara River. Here, even if the current proposal for replacing the federal Clean Water Rule is adopted, it would remain illegal to dump old tires or car batteries, garbage, mine tailings and other toxic waste products into creekbeds that may be dry much of the year.

But many other states have no such law. If Clean Water Act protections for wetlands and intermittent and ephemeral streams go away, well…so could the trout and salmon that rely on these habitats.

Sam Davidson is TU’s communications director for California and Oregon. He highly recommends prospecting for trout in the desert.