Trout Unlimited’s efforts with the University of Maine and the Maine Department of Inland and Wildlife to develop eDNA sampling methods for Maine’s rare Arctic char continue.

As described in a recent TU story, we’re focused in Maine on the handful of remaining populations of landlocked Arctic char, a glacial relict that’s been slowly losing populations over the last 120 years.

Char exist only in deep, cold, large lakes with minimal competition from other fish species. They co-exist with brook trout, but non-native fish — rainbow smelts that compete with char, landlocked salmon that eat char, and lake trout that may prey on or interbreed with them — have eliminated char from historic habitat in New Hampshire and Vermont and impacted at least three of Maine’s 12 remaining native populations in recent years.

I’ve been fishing Maine for more than 40 years and catching a char has been on the bucket list for most of that time.

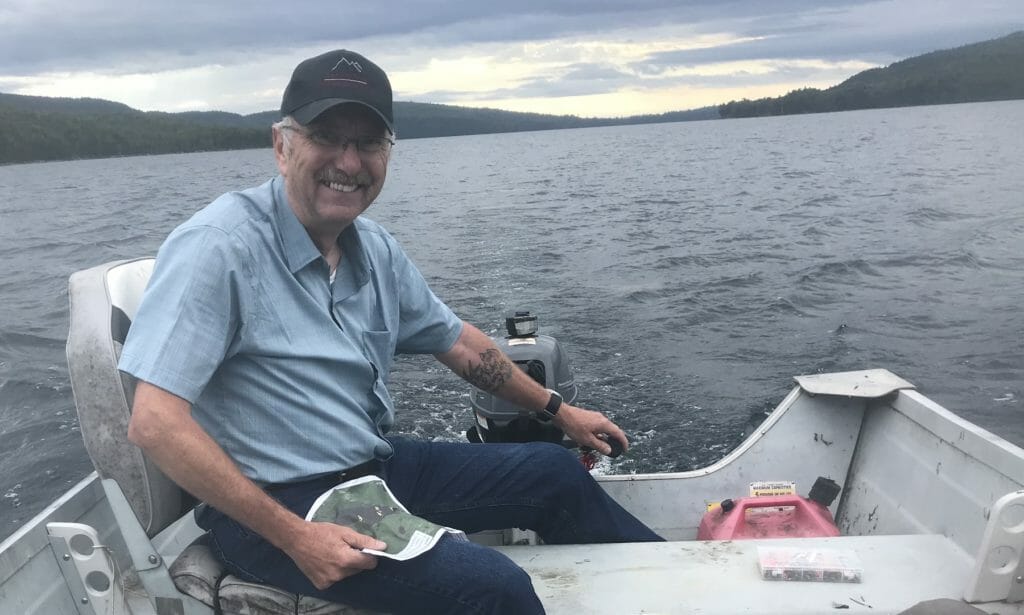

I finally got my chance in early September with long-time trout volunteer Leon Emery (above).

Leon owns a small chain of Maine butcher shops, and I’ve rarely eaten better on a fishing trip than the Remote Pond Survey Trips where Leon supplied the meat. He’s also a devoted angler with a fondness for Rainbow Lake, one of Maine’s most remote large lakes. Leon first fished Rainbow Lake when he was 6 — more than 50 years ago. Now in his 60s, he still makes two trips a week. As I learned, it’s not easy.

Leon and I met at 1 a.m. and left my vehicle in a park and ride lot. From there, it was two hours to the end of pavement in the tiny village of Kokadjo, and another two hours on rough logging roads to a trailhead near Nahmakanta Lake.

We were hiking in the dark a little after 5 a.m. Two miles up the trail, with just enough light to see, we found the canoe and a small outboard Leon keeps stashed in the woods, and were on our way up the Rainbow Deadwater, a wide spot on Rainbow Stream.

A mile and half of that brought us to a short portage from Rainbow Deadwater to Rainbow Lake, where Leon keeps a small boat. Our goal was to be on the lake by 6:30 so we could collect our samples before the white caps built on the lake, and we were pretty much on schedule.

Leon piloted the boat to 10 GPS waypoints. As we approached each, he’d turn the boat into the wind, and bring it to a stop right on our sample location. I deployed the sampler as we slowed to a stop, dropping it a measured 16 meters to get water at the right depth. Two and half hours took us on a big circle around the lake and back to our starting point. After we sealed and secured the samples to prevent contamination, that left us about two hours to fish.

There’s a lot to be said for local knowledge. Trolling small spoons on lead core line to get down to the 40-foot depths where char feed, Leon had us into our first brook trout within 10 minutes of dropping the lines.

The fish came steadily until we quit — a mix of brook trout and char. I got my bucket-list char, and then I got three more. We swiped each fish with a Q-tip to collect a slime sample for the UMaine crew to analyze population genetics.

Leon had been collecting swipe samples all summer. The only sour note of the trip was our second-to-last fish, a small landlocked salmon (above). Salmon showed up in the lake a few years ago, and the fear is that once they establish a reproducing population, Rainbow Lake will see its char decline as so many other Maine lakes have.

This one was a small juvenile, raising concern they may found a place to spawn. We killed it and delivered it to for analysis of DNA and scales that may help determine its origin.

After delivering our samples to the UMaine crew, I was home at 10 p.m., after a 22-hour and very rewarding day.

Jeff Reardon directs Trout Unlimited’s work in Maine. To learn more about TU’s volunteer opportunities in the state, including survey efforts to locate native brook trout in remote pondsand salter brook trout in streams, email him at jeffrey.reardon@tu.org.