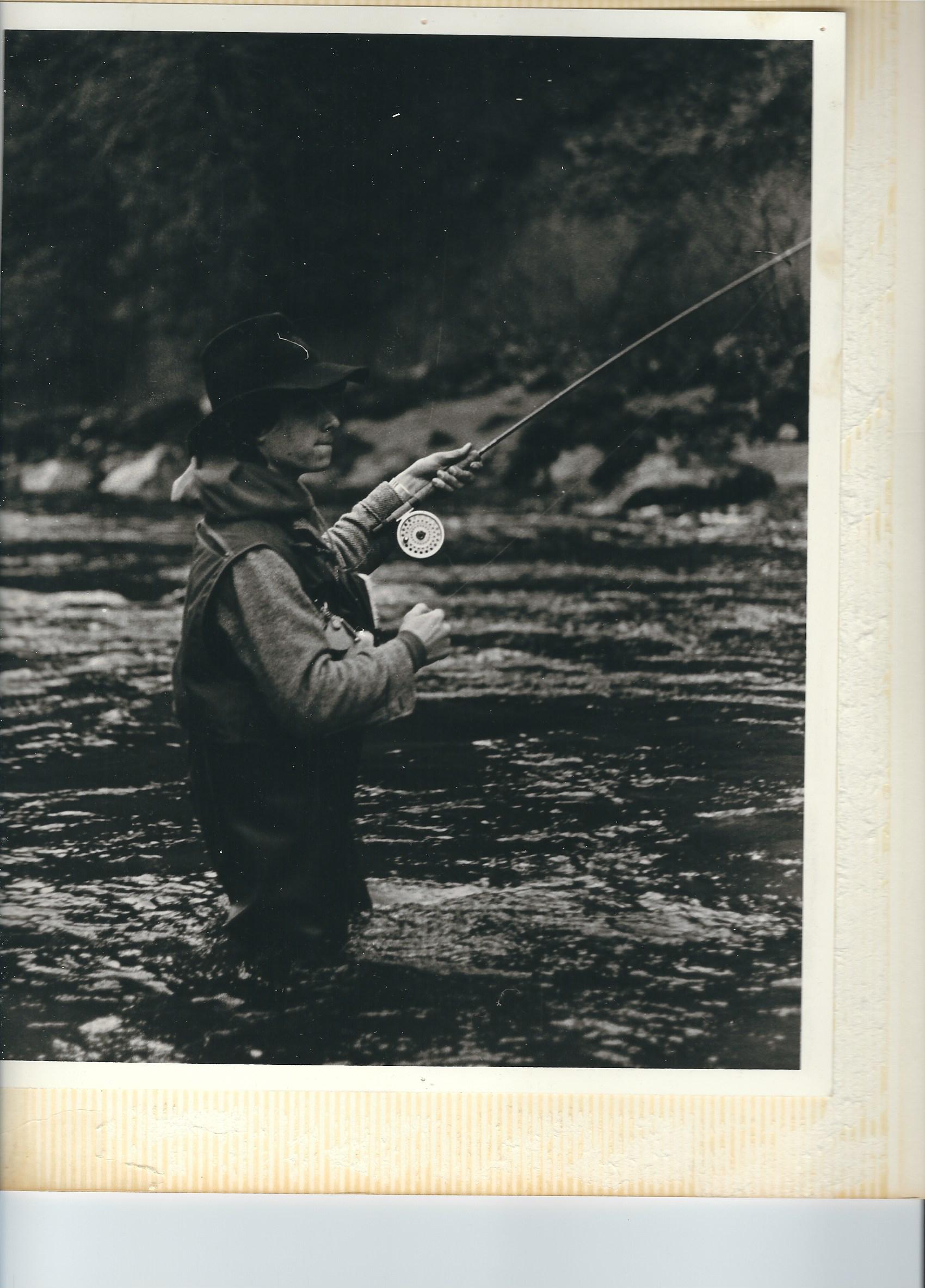

TU’s Dean Finnerty fishing the Sandy River as a teenager.

By Sam Davidson

Ten years ago, on a river revered for its huge wild steelhead, more than a ton of dynamite reduced a 47-foot high dam to rubble.

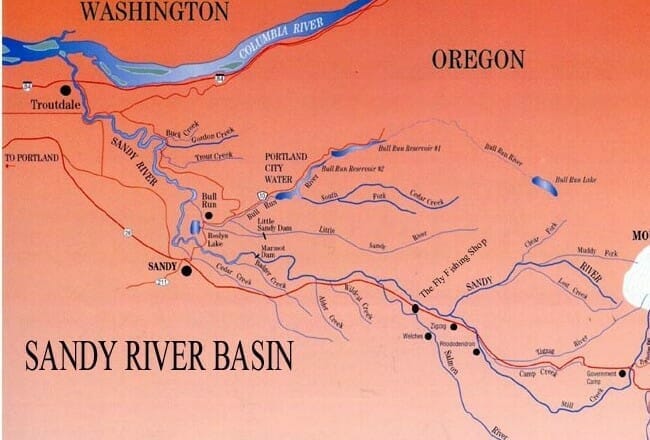

The dam was named after a whistling rodent and the river after a big sandbar early European and American explorers observed at its confluence with the Columbia River.

After the explosives and bulldozers were finished, Marmot Dam, the centerpiece of Portland General Electric’s Bull Run Hydroelectric Project on Oregon’s Sandy River, was no more. At the time, it was the largest dam ever removed in the United States.

As with subsequent dam removal projects on rivers such as the Penobscot, Elwha and Carmel, it didn’t take long for migratory fishes such as salmon and steelhead to begin moving into the upper reaches of the Sandy River, habitat they hadn’t reached for more than a century.

The Sandy River begins on the flanks of Mt. Hood and flows for 56 miles to its juncture with the Columbia, about 14 miles upstream of Portland. The Sandy retains a scenic and wild character despite flowing through a heavily populated region, and has the reputation of being one of the best year-round steelhead fisheries in the Northwest.

The Northwest Regional Director for TU’s Sportsmen’s Conservation Project, Dean Finnerty, was raised in the area and fished the Sandy often as a youth. Finnerty has caught more native steelhead in western Oregon rivers than any one person has a right to. Before coming to TU, he pursued a dual career in law enforcement and guiding.

It turns out Finnerty also could have earned his keep as a bard. Upon learning of ODFW’s announcement regarding salmon and steelhead numbers in the Sandy, he sent me this reminiscence:

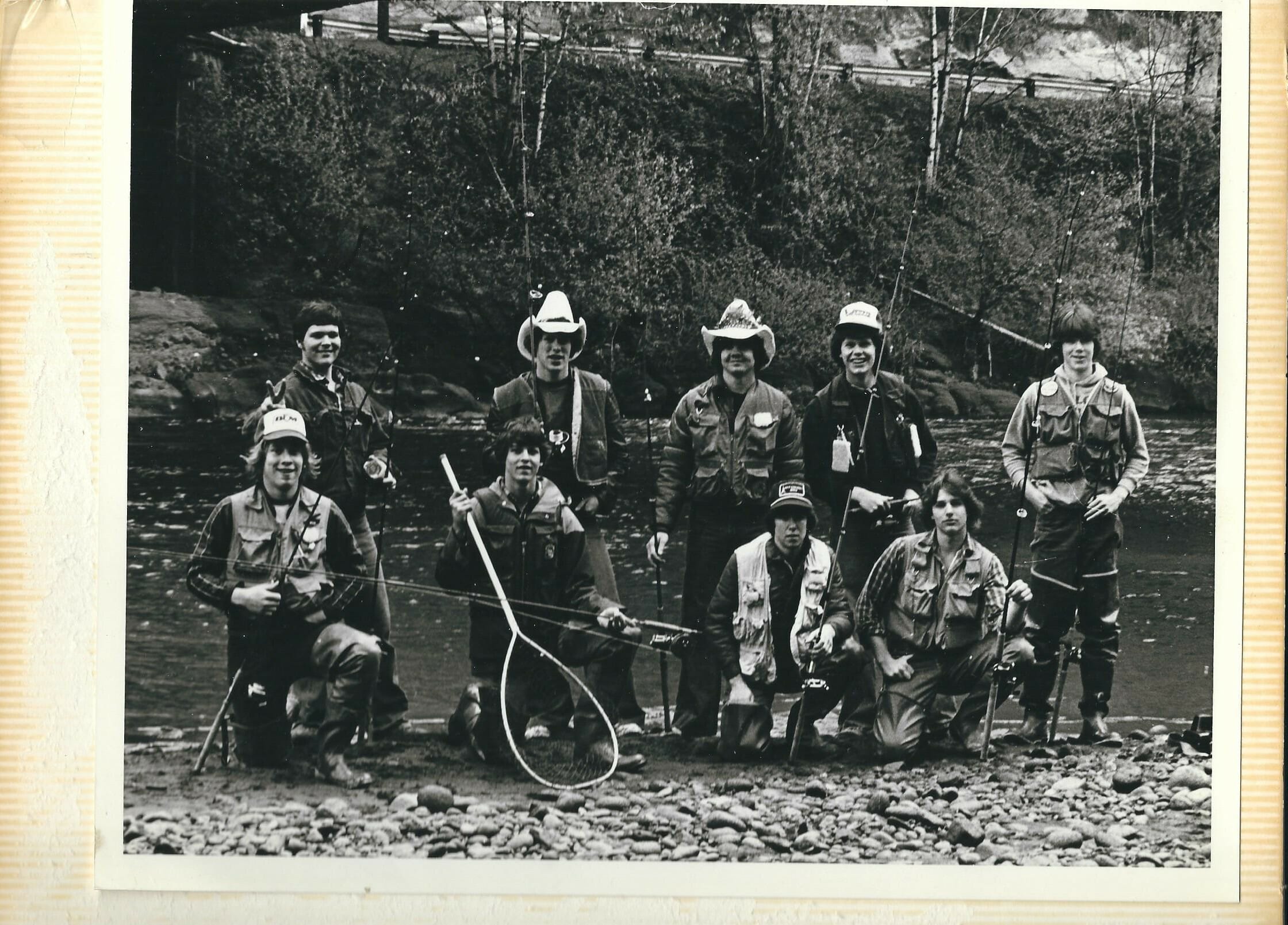

I grew up on the Sandy and began my guiding career as a teenager on the Sandy and Clackamas Rivers. We had winter steelhead, coho and spring chinook. We also had summer steelhead on an upper Sandy tributary called the Salmon River. That’s where I caught my very first steelhead on a fly in 1979 or 1980. The Bull Run River (another trib) also had summer steelhead.

The native winter steelhead on the Sandy used to be legendary for their size (20 plus pounds). My first steelhead was hooked on a spoon called a “steelie” near the mouth of the river. It was on my 12th birthday, which would have been 1976. It was huge and my dad guessed its weight at a little over 20 pounds.

(R) Dean Finnerty’s high school fishing club (Barlow H.S.) on the banks of the Sandy River, circa 1980.

(R) Dean Finnerty’s high school fishing club (Barlow H.S.) on the banks of the Sandy River, circa 1980.

My brothers, friends and I used to fish every summer below Marmot Dam. Jim Teeny’s dad drowned there during this time, trying to cross the river in a float tube to reach a great run on the other side of the river. We used to catch a lot of summer steelhead below the dam.

The effort to remove the dam actually began with Mark Bachmann and some of his fishing buddies back in the late 1960s. Frank Amato, Bill Bakke and I believe John McMillan’s dad [science director for TU’s Wild Steelhead Initiative], Bill, were also involved in that early effort. Bunch of crazy hippies!

I have a lot of fond memories growing up there and I’m thrilled the Sandy runs wild and free today.

There is no longer much question, if there ever was, about the benefits of dam removal for anadromous fish species. But it’s easier to apply the C-4 blasting charge to some dams than to others. Older dams that no longer provide much hydropower (such as Marmot Dam, and those stair-stepping the Klamath River below Klamath Lake), have become structurally unsound, or that cannot be modified at a reasonable cost to facilitate passage of imperiled fishes are the best candidates for removal.

As America watches with keen interest the current debate over what to do about the deadly effects of the lower Snake River dams on Columbia River salmon and steelhead, you can stoke your fishing and advocacy fires by watching this time-lapse video of the demolition of Elwha Dam.

Get more information on TU’s wild steelhead work in Oregon.

Sam Davidson is Communications Director for TU’s California and Klamath programs. His home river, the Carmel, has undergone a remarkable transformation in recent years with the completion of the San Clemente Dam Removal and River Re-route Project.