The tones went off at about 2:30 a.m., and I rolled out of my bunk at the fire station, rubbing sleep from my eyes. I stepped into my bunker gear and slid my arms into the sleeves of my coat like an automaton. The dispatcher’s voice was calm and measured despite her dire message: “Engine 427, Medic 427, EMS Supervisor 405 respond to the shooting at…” She continued rattling off numbers to a street address in our response area. Less than 90 seconds ago my entire station’s crew had been sound asleep; now someone needed our help.

Once seated in the engine, I pushed the “enroute” button on my computer screen, letting the dispatcher know that our units were responding. The computer chirped in response, and the glow from the screen outlined my driver’s stoic face. Without speaking, he cut on our emergency lights, turn- ing everything around us red. As we left the station, our sirens pierced the early morning stillness and drove any remnant of sleep from my mind. A gut instinct told me this one was going to be bad, so I asked for more help. “Engine 427 to Fairfax, I’m requesting a med- evac helicopter for this call. Tell them to use West Springfield High School’s football field as a landing zone.”

Moments later my crew and I were tightly huddled around the victim, who was lying on the kitchen floor of a small brick rambler in a quiet neighborhood in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. A male in his mid- 20s, he had a single large-caliber bullet wound under his left clavicle. He was pale, staring into nothingness. His mouth gaped open. Blood oozed from his chest wound. Kneeling over him, I observed a hole from the gunshot large enough to drop a quarter into. I could actually look down into his chest and see his left lung.

Two police officers were already on the scene by the time we’d arrived. One of them was holding direct pressure on the wound, and the other had secured the weapon and radioed that it was safe for us to enter. The three young men who were also occupants of the house stated that they had been drinking most of the night and that eventually some- one had suggested a game of Russian roulette. The young man on the floor had recently returned from Army ser- vice in Afghanistan. He had survived a war zone only to be shot at home.

The room became a sudden blur of activity as my crew and I did what we were trained to do. We took the young man’s vital signs, administered oxygen and placed IVs into both arms. Our cardiac monitor indicated a highly accelerated heart rate: his body’s desper- ate effort to compensate for his drastic blood loss. I listened to his lung sounds, and then we quickly rolled him over onto his side. Not finding an exit wound, we gently placed him on a backboard. Once secured to the board, firefighters and police officers alike struggled to hustle the motionless victim to the transport unit outside.

We soon arrived at the landing zone, and I yelled my medi-cal report to the flight medic over the roar of the rotors. The flight medic’s badge flickered like a candle in the ghastly light coming from all the emergency equipment on the scene. The flight medic nodded and patted me on the back as if to say, “Thanks, Captain—we have it from here.” The helicopter rose, whipping up its own storm, blowing grass, dirt and bloody bandages across the football field. Following their lights into the night sky, I wondered if the young soldier would make it and said a silent prayer for him. None of my crew members said a word; we simply began picking up our gear and headed back to the station.

Running an emergency scene like the early morning shooting I just described feels as though you’re part of some grotesque and bizarre dance— and your dance partner is death itself. One wrong move, one misstep, just one missed cue, and you know the dance is over. The whole scene takes on an intensity that is incredibly fast paced, and yet you seem to be moving in slow motion. The faster you want to respond and react, the longer and more difficult it becomes.

Dealing with these kinds of high stress events—over and over again for years—takes a physical and emotional toll on first responders. Their family life is often strained because fire and police stations never close—not even for holidays. The worse a call is, the less likely a first responder is to share such graphic scenes with their loved ones, especially their children. This can lead to a sense of isolation and the belief that no one really understands them; over time this can end in despair. I remember my instructor in recruit fire training said, “Whatever you do, don’t ditch your civilian friends. You’re going to need them to help keep you sane if you stay in this line of work.”

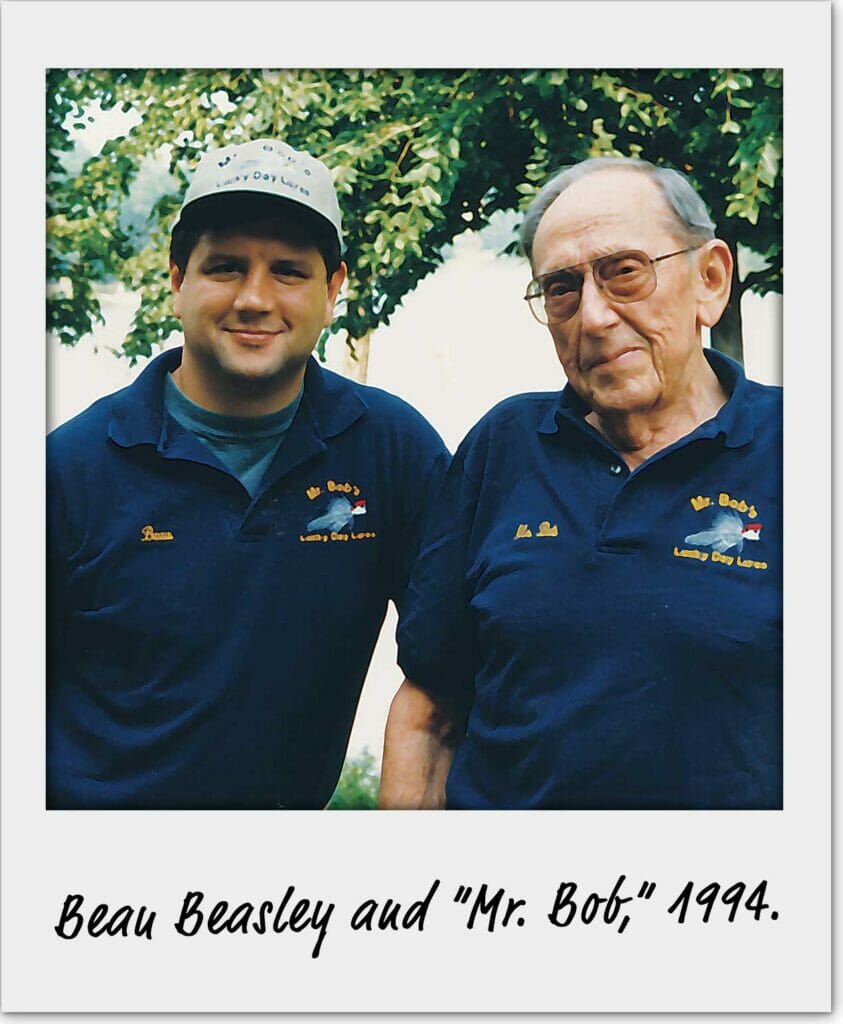

About 10 years into my career, this admonition would play itself out when I ran a call that would change my life. I responded to Burke Lake Park for an elderly gentleman who had been stung by a bee and was having difficulty breathing and irregular heartbeats. The kindly old man was initially reluctant to go to the emergency room, but I convinced him that it was better to be safe than sorry. Seeing the apprehen- sion in his face during our transport to the hospital, I decided to exert some good old-fashioned bedside manner and asked him if he had ever fished in Burke Lake. He told me that he regularly caught bluegill and bass there on pop- pers that he tied himself. Later I would discover that my patient was Bob Guess, one of the best- known popping bug makers in the county. When I mentioned to him that I’d always wanted to learn how to fly fish, Bob offered to teach me on the spot. A week later Bob and I were in a jon boat back at Burke Lake, where I landed my first fish on a fly rod with a popper that Bob had tied.

Bob revealed to me that with a pair of waders and a handful of bass flies, I could escape my world of lights and sirens and enter another in which I could hear the buzzing of a passing dragonfly, witness bass chasing minnows on the shoreline, or watch the rings emanating from a rising trout.

Bob bought me my first fly rod, and we traveled and fished together for many years. I quickly discovered that I love every- thing about fly fishing. I love the scenery, the sound and movement of the water that can lull you to sleep if you’re quiet enough, the thrill of catching a fish. I love the peace. Fly fishing allowed me to distance myself from the horror I saw at work, and it restored a sense of calm. Bob revealed to me that with a pair of waders and a handful of bass flies, I could escape my world of lights and sirens and enter another in which I could hear the buzz- ing of a passing dragonfly, witness bass chasing minnows on the shoreline, or watch the rings emanating from a ris- ing trout. Even though Bob passed away about 20 years ago, I still have some of his popping bugs, and I think about him every time I drive by Burke Lake.

Not every first responder gets to benefit from a relationship like the one I had with Bob, but that may be about to change. For years Trout Unlimited has reached out to veter- ans of the armed services through its Veterans Service Program; now TU has expanded this effort to include first responders.

About a week after responding to that early-morning shooting, I received an email from a high-ranking officer at headquarters. The message was simple and forthright: “Tell your folks they did a great job at the shooting—and let them know that the soldier made it.” I called my crew into the fire station kitchen and shared the good news: My prayer had been answered.

If I were ever to see that young soldier again, I’d offer to just sit and listen to whatever he wanted to tell me (or not tell me) about what he’d seen in Afghanistan. I’d let him know that I too am haunted by what I’ve seen—and by the cries I’ve heard from those I couldn’t save. I’d tell him he’s not weak, or crazy, or broken—he’s human. And then I’d offer to take him fly fishing.