By Cal Curtice

"This is probably the last generation of trout fishers."

— Forest and Stream Magazine 1879

In 1620, virgin forest covered the United States from the tip of northern Maine, south to central Florida, and west beyond the Mississippi River. Native brook trout swam throughout their cool, clean waters, including those in the Finger Lakes and Upstate New York where we live.

By 1926 only 9 percent of this virgin forest remained intact, as huge swaths of forest were removed to make way for an expanding civilization. Along with it went the brook trout that only survived on the edges of remote wilderness. It was a collapse so bleak that Forest and Stream predicted the end of the trout fisher in 1879.

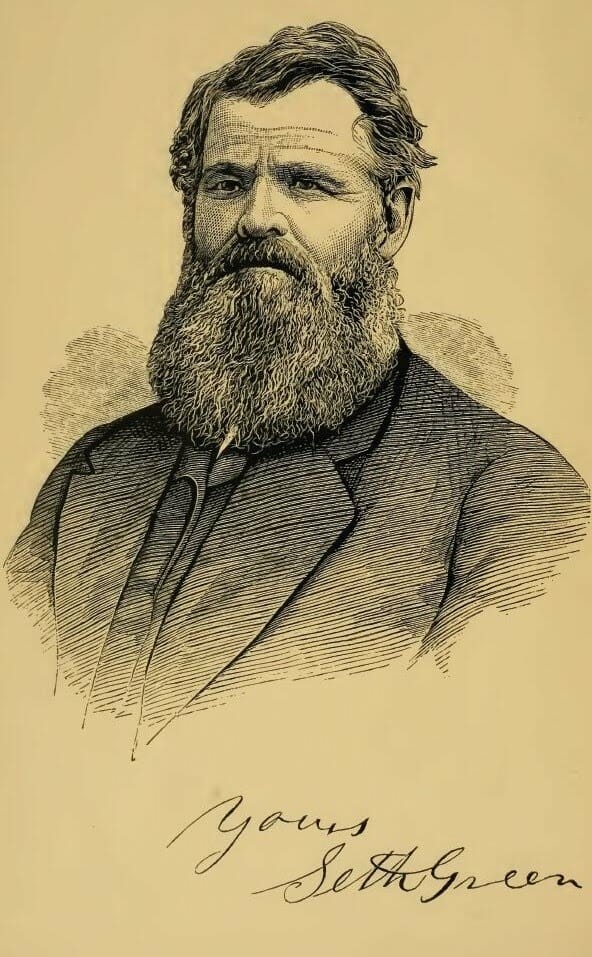

Seth Green was born in the Rochester area in 1817, learning about nature from the Seneca people. He was an obsessed fisherman who grew to such local prominence that even the native people who had lived off the land for thousands of years, considered him an expert. He started a fish market along the Genesee River and was deeply concerned by the decline of the fishery.

Green spent hours studying salmon of Lake Ontario spawn in pools of the river and was determined to find a way to simulate the natural process to restore fish populations to the area. By the time he was done, he invented the highly effective dry impregnation process and became one of the most famous Americans of his time.

His early trials took place in a hatchery he built in 1864 on Spring Creek in Mumford, N.Y., about 25 miles south of Rochester, which still stands today as the oldest hatchery in the western hemisphere. The consistently cold water bubbling up from the ground provides ideal conditions to experiment with trout eggs imported from the mountain streams of Germany. In June 1886 a fly fisher caught an unusually colored large trout from Oatka Creek and sent it to the New York State fish commissioner.

It was notable enough to be reported in the New York Times and was one of the first brown trout caught in North America. Within 30 years salmo trutta was distributed throughout the United States and parts of the world. Seth Green and fish culturists of his time had found a way to keep fly fishing alive by stocking a trout tolerant of the new environment civilization had created. Our chapter is named after him and the stream where his first brown trout was caught declined and faces a new kind of threat.

A World of Extremes

“Suitable habitats will be shrinking for some species such as coldwater fish like brook trout”

-— National Climate Assessment 2018, Northeast Quadrant

Rochester is a cold place to live in winter, averaging about 100 inches of snow each season, but the winters’ of 2014 and 2015 were extreme even by our standards.

Meteorologists called those winters “polar vortex” events where a low pressure system that typically hangs over the north pole weakens and moves south where it can linger until the jet stream pushes it back. While the weather at the north pole is comparatively balmy, parts of the U.S. are in a deep freeze. During these two years, most embayments and near shore water in our area completely froze over, driving fish eating ducks inland to survive.

The summer of 2016 brought unrelenting heat and drought, the inland streams were so low and warm that the Caledonia hatchery had to install mechanical aerators to keep fish alive. The area had experienced three consecutive years of extreme conditions and trout were under tremendous pressure trying to survive.

In April of 2014, I stood in Oatka Creek with a dozen other anglers watching the Hendrickson hatch come off in clouds. No fish rose to eat them. The Department of Environmental Conservation was inundated with calls from anglers asking what was going on at our beloved wild section of Oatka Creek Park. The DEC shared their most recent fish sampling and confirmed a precipitous decline, theorizing that the Mergansers had moved inland and found a place to survive in Oatka Creek.

Not in Our Backyard

“Dude, we’ve got to do something.”

— Jesse Hollenbeck, Seth Green Trout Unlimited chapter president

There was uncertainty and even disagreement within our angling community about what was causing the poor fishing at Oatka and Spring creeks, but there was also universal concern.

Jesse Hollenbeck, a fellow passionate fisherman and guide, rounded up several members of his circle to work with our local Trout Unlimited Chapter. There is no better way to express concern than to fix a problem directly, and so we all joined the board under President Larry Charrette.

We had energy and passion, but not the experience, money or knowledge to start a conservation project. Looking back on it now, there were three critical initial steps that acted as a catalyst: a site walk-through with U.S. Fish and Wildlife, applying for an Orvis retail grant, and organizing a film night that energized the community.

Those three activities gave us the start we needed — and then we replicated them for other grant opportunities and community engagement. We hosted annual movie events, applied for a Trout Unlimited Embrace A Stream grant, competed in the Embrace-A-Stream Challenge (your chapter really should experience this), and had further targeted site assessments with USFW, the New York Department of Environmental Conservation and Monroe County Parks, which owned the property where the work would be done.

Within a couple of years, we had $35,000, a habitat improvement plan with our partners, a motivated chapter, and a date to install structure.

In August of 2019, equipment from our contractor CP Ward was staged at the Oatka Creek Park access lot and stone was delivered for the habitat installations. Our goal was to install 35 sites over about a mile of stream that was identified in our targeted assessment as a habitat-limited section.

The park had many dead trees that could be used for root-wad installations. They would be driven into the side of the banks and pinned down with stone. On the first morning, the parking lot was filled with TU volunteers, DEC, USFW, Monroe County and contractors drinking coffee and verbally putting the plan together. Honest to God, there was a brightly lit rainbow spanning the stream as the sky cleared from a light pre-dawn rain. It was a nice moment.

We’d heard that experienced contractors were very important and went to great lengths to lock one down for the work. In our case, this involved getting a week from a retired operator that had worked on several previous habitat installations. The level of independence and trust given to equipment operators was more than I originally anticipated — they were shown the section, the plan, and then left alone for most of the two weeks to get it done.

There were good and bad locations for habitat installations, mostly trying to avoid the slate bottom that was common throughout this stretch. The process to install a habitat structure was pretty much the same and done repeatedly where they were needed. The team would pick a dead tree of the right diameter, pull it from the ground with the rootwad intact, cut it to length with a chainsaw and creat an arrow-like point on the end to make it easy to drive into the bank. The it would be picked it up with the thumb attachment on the heavy equipment, drove it into the bank for about 10 feet just beneath the water’s surface, and then pinned it in with the stone on either side.

A road needed to be built along the streams edge and hundreds of two-ton stone pieces were carried and left near the sites for installation. Of course a series of unexpected problems arose: equipment stuck in the mud and broke down, operators with appointments, and the usual slings and arrows life throws at you.

Each was overcome as they appeared through a series of decisive action from volunteers. After two weeks we had 70 installations in place and our slotted time with the contractors was complete. Walking back through the work area after everyone was gone I saw four mergansers silently gliding midstream past the installations.

We hosted a chapter event to walk-through the project site in late August and had a good turnout. It was almost surreal to be there thinking back on the original conversations we had when we joined the chapter.

We certainly didn’t know what we were doing or what it was going to take to get something done but it ultimately didn’t matter. We were simply determined to do something about it. A group of us walked down through the project stretch, stopping along the way to show what was done and how the installations would provide cover for fish.

It would give fish a fair shot of survival in an area that had previously left them exposed to predators. The project didn’t belong to anyone, but to the entire community that made it happen. You could feel the sense of pride and accomplishment in the air from everyone.

During the Embrace-A-Stream challenge, we received a $10 donation “in memory of my grandpa,” a $20 donation for “my daughter’s favorite place,” and an anonymous donation of $1,000.

During the tour, we walked up to one of the installations in a beautiful stretch lined with willow trees, one of the more popular areas to fish. I walked out on a tree that stuck into the bank for cover and clouds of mud plumed all around as a few brown trout exploded out from underneath their new hiding spot.

They were carrying the genes of the fish Seth Green put in there 150 years ago, perhaps the last time the natural world changed so dramatically that a fellow angler decided something had to be done about it.

References:

Black, Sylvia R. (July 1944). “Seth Green Father of Fish Culture” (pdf). Rochester History. Rochester Public Library. Retrieved 2014-08-19.

Green, Seth (1870). Trout Culture (pdf). Rochester, New York: Seth Green and A.S. Collins.

Cal Curtice is the conservation director of the Seth Green chapter in Rochester, N.Y.