Have you ever heard of moose tartar? Did you know herring eggs taste how the sea smells? How about that you can make ice cream out of seal fat?

I didn’t either. Until I attended United Tribes of Bristol Bay’s Traditional Foods Feast in Dillingham, Alaska. Dillingham is a fishing village perched on the glistening waters of Bristol Bay; a region synonymous with ground zero of the proposed Pebble Mine.

The Pebble Project, a proposed gold and copper mine, has potential to wreak irreversible damage to Bristol Bay and the world-renowned salmon and trout fisheries that it supports. The fight against it has persisted for nearly two decades.

At the forefront of said fight stands United Tribes of Bristol Bay (UTBB), bracing against threats that would forever change their home and subsistence way of life. UTBB is a consortium of 15 federally recognized Yup’ik, Dena’ina, and Alutiiq Tribes that have banded together to self-determine a sustainable and fish-filled future for Bristol Bay.

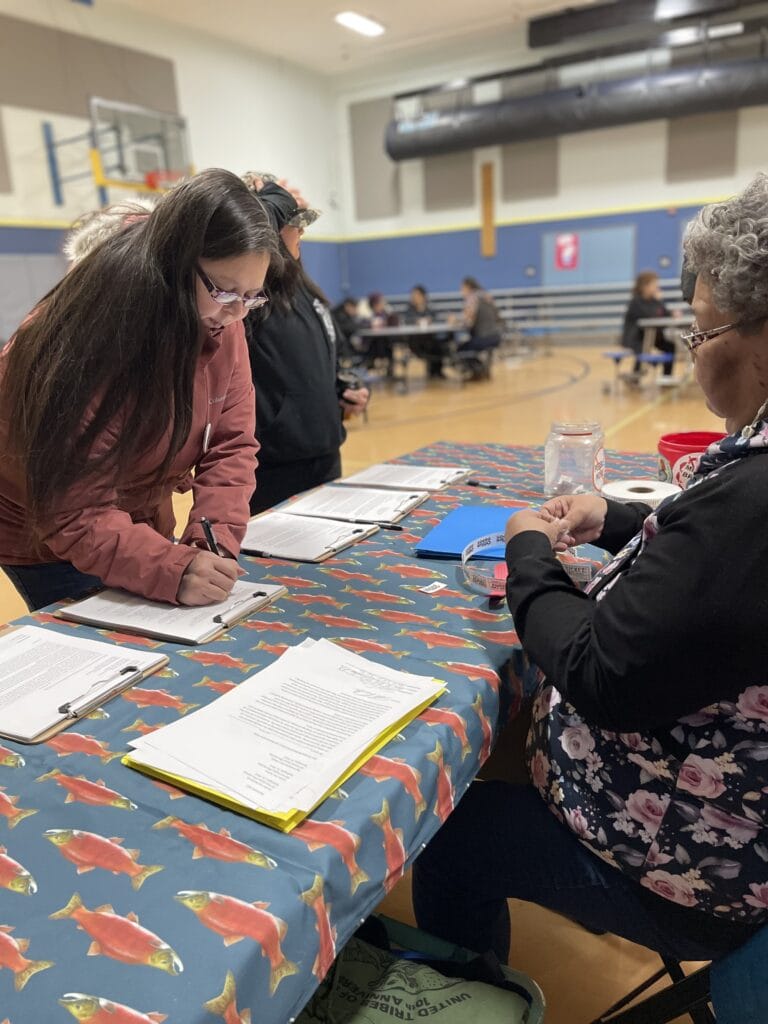

In my work for Trout Unlimited Alaska, I always relish in opportunities to step out from behind the computer screen, into the region that our team works diligently to safeguard. The occasion for my trip to Dillingham was to screen School of Fish, a short film sponsored by Trout Unlimited and Orvis, at UTBB’s Traditional Foods Feast.

School of Fish celebrates Triston Chaney and his family. Triston is a 24-year-old fly fishing guide, commercial fisherman, and subsistence harvester. All aspects of his life and work are threatened by Pebble. As young as he is, Triston already has nearly 15 years of testifying against Pebble under his belt. That’s too long.

For the elders in the room at the Traditional Foods Feast, that number is even bigger. These people of Bristol Bay are tired from this long-lasting fight. But they have much to celebrate with Clean Water Act protections, that safeguard the waters around the Pebble deposit, which were granted this past year. What better way to do that than by coming together in community, with food from the land.

UTBB defines traditional foods as those coming from the lands and waters of Bristol Bay. Revered on an international scale, the bounty of Bristol Bay’s salmon runs is unparalleled. The knowledge that this region of abundance still exists has motivated millions of people across the world to call for permanent protection for Bristol Bay. To experience the quality and variety of traditional foods harvested from these bountiful lands and waters was a privilege.

“Wealth for my family is measured in not how much money we have in the bank, it’s how much food we have in our freezers and how much we give away.” Says Robyn Chaney, Dillingham subsistence fisherman and Bristol Bay advocate. At the foods feast, this wealth was apparent.

So, what did we eat? Lots of salmon for one. Pickled, baked, smoked salmon. Salmon dip, soup, jerky. Other dishes from the water included whale skin and blubber (Mangtak in Yup’ik), herring eggs on seaweed, dried northern pike. Foods from the land included salmonberry jelly, blueberry and seal fat ice cream, and moose meatballs. The list goes on. I left the event feeling not only nourished by these wild foods, but with some hearty food for thought as well.

In my work advocating for a fish-filled future for Bristol Bay, I always find myself referring back to the statistics; 96% of local households rely on subsistence fish, culminating in over 500,000 pounds of salmon being consumed annually. That translates to $4,500-$9,000 of vital nutrition per household.

This event reminded me that beyond the numbers, there’s a much deeper truth. The strength, resilience, and community bonds formed by subsistence life are forces that far transcend facts and stats. The people of Bristol Bay don’t need a mine. They have their gold; the region’s bounty of wild foods.