by Mark Konishi

Growing up in the San Luis Valley, I would hear rumors of cutthroat trout with vivid colors caught in secret waters. Cutthroat trout with orange slab-sides as brilliant as any goldfish.

Many of these stories often came from my classmate Jim, relayed down through his extended family. It was difficult to pinpoint precisely who in Jim’s large family caught the unusually colored cutthroats, not to mention where these rare fish swam, but the prospect of catching a cutthroat the color of a goldfish was too much to bear. So, every spring, I would grab my Eagle Claw Trailmaster rod and my Pflueger automatic reel, and the quest would begin. After several years, my friends and I surmised stories of this cutthroat trout of gold were just fish stories.

As I reached adulthood, I realized I had searched the wrong streams for this elusive native trout. I also learned these fish with orange bodies had a name, the Rio Grande cutthroat trout. This rare fish is the native fish of the Upper Rio Grande drainage and was the first trout documented in the New World by Europeans (Francisco de Coronado) in 1541.

When I finally hooked my first aboriginal (a fish never stocked by a modern man) Rio Grande cutthroat trout, a surge of adrenaline dumped into my bloodstream. I concentrated very hard to remember all the proper techniques to ensure the fish wouldn’t shake the hook from its mouth:

- Rod tip up

- Keep tension on the line

- Carefully play the fish so as not to snap my 7x tippet

- Net the trout from the front

My hands were shaking as I brought the fish into the light. In my net was the most beautiful fish, with a most brilliant orange body. In my hands was a direct descendant of the original fish, which has plied the waters of the upper Rio Grande drainage for millennia, far longer than man has lived on this land.

A bit of Rio Grande cutthroat trout history

The Rio Grande cutthroat trout currently occupies roughly eleven 11 percent of its historic range. Through years of settlement and development in the upper Rio Grande drainage, many decisions have impacted our native trout, including the stocking of non-native species. The well-intended actions of conservationists attempted to ensure no harm would befall the native fish, but the damage often resulted in severe consequences. Since European settlement, one cannot deny the adverse impacts of mining, logging, non-native stocking and other unfavorable events.

Over the years, man created a broken story in the history of this native fish.

In 2008 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined the Rio Grande cutthroat trout warranted protection but reversed its position in 2014, thanks to concerted restoration efforts. In September 2019, a federal judge ruled that this decision reversal was arbitrary and unlawful in response to a lawsuit. The finding meant the agency must reconsider listing the trout under the Endangered Species Act. As a result recovery efforts must continue to remove them from potential listing.

We have a legal and moral obligation to return lost chapters to the story of the Rio Grande cutthroat trout through preservation efforts to recover the species.

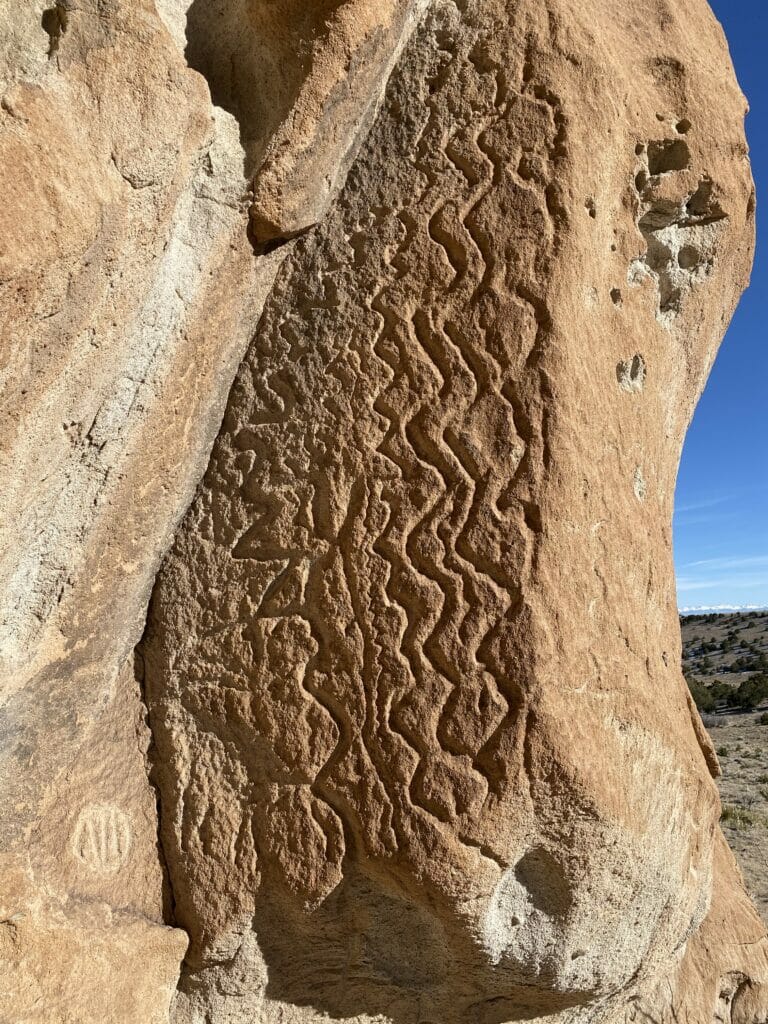

For at least 12,000 years, humans have written his story on the rocks of the Upper Rio Grande. Today, nobody knows what the petroglyphs say. Faded legends and time over the centuries have erased their meanings. Modern humans don’t have this problem in documenting our actions or inactions. An eternal record of our conduct and actions in preserving the fish—or failure to do so—will be recorded for eternity. What will our story tell generations into the future? Will they be pleased when they catch a descendant of the Rio Grande cutthroats of today, or will they have to be satisfied with reading the history of a lost species and a picture?

Fishing for Rio Grande cutthroat today

I only fish with a bamboo rod when pursuing native trout. It just seems like the proper tool—showing respect for such a rare fish.

Every Rio Grande cutthroat trout I hook, takes my breath away. No matter how many I’ve caught through the years, the fish resurrects an emotional response from within.

Possessing such beauty, I think this fish would even cause a non-believer to pause and wonder; how could something this beautiful not have the fingerprints of a higher entity?

I think of the previous generations of the fish I am holding and contemplate the connection to the ancient Indigenous people who once walked this land. Were they as stunned and astonished at the beauty as I? Adequate words escape me, but did they have the diction to express their emotions?

Perhaps all I do know, is that the world seems right when I am in these proper places.

Mark Konishi is a Trout Unlimited volunteer.