By Rob Shane

For those in the Mid-Atlantic, or for anyone who’s been trout fishing long enough to have a bucket list of rivers, you’re certainly familiar with the Delaware River.

Aside from being the source of drinking water for more than 15 million people in two of the largest cities in the United States (New York and Philadelphia), it provides so much more to all of us who rely on the Delaware for their livelihood, a source of escape from every day life, and a place to call home.

Earlier this month, American Rivers named the Delaware its River of the Year. It’s a prestigious designation that those of us who know the story of this river’s troubled history and have worked hard to change that narrative know did not come easy.

Before George Washington famously crossed the Delaware on Christmas night in 1776, the basin was home to the Lenni Lenape tribe – the first to recognize its value and cherish its bounty.

The tribe’s territory spanned the entire length of the river, from its headwaters in New York to the mouth in Delaware Bay. The great Lenape people thrived by harvesting migratory returns of American Shad and growing crops in the fertile valleys of the Delaware River.

The Delaware River is also the birthplace of American fly fishing.

Although disputes continue about whether the Catskills in New York or the Brodhead Creek in Pennsylvania can officially claim the title, all who enjoy the sport can thank the cold, clean water in the Delaware Basin for the sport as we know it.

With the introduction of fly fishing in the upper reaches of the Delaware in the late 1800s also came some of the earliest stories of coldwater conservation. We at Trout Unlimited can thank these founders, at least in some small part, for our own existence today.

The story of the Delaware River took a turn, though, as industry took precedent and water quality quickly became a victim of growth and economic prosperity.

Timber harvest, coal mining and manufacturing giants such as Bethlehem Steel were fueling the American industrial revolution. Alongside these prosperous industries came booming metropolitan populations, roads, parking lots and lots of impervious surfaces.

At one point, the river’s water was so foul that it would turn the paint of ships brown. Vast sections of the river were void of aquatic life.

Enter the Clean Water Act in 1972, and the story of the river started to shift.

Because of these new regulatory tools, as well as the effort of the newly formed Delaware River Basin Commission, the river’s health improved. Dissolved oxygen levels, which had been extremely low or even non-existent in some parts of the river, began to increase. Phosphorous and other harmful chemicals started to disappear.

With the resurgence of clean water, migratory fish such as American shad, striped bass, and Atlantic sturgeon returned.

Coincidentally, at the beginning of the River’s resurrection in the 1970s, communities upriver in the Pocono Mountains were fighting a battle that would ultimately define the future of the River as we know it today.

The proposed Tock’s Island Dam, near the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, would have been the largest east of the Mississippi, creating a lake nearly 37 miles long and flooding one of the most popular National Park Service units in the country.

Local advocates fought this flood-control dam tooth and nail, refusing to see their beloved river and its history needlessly buried behind a man-made structure.

And they won.

Today, the Delaware River remains the longest undammed river in the Eastern United States, flowing freely for 330 miles from the confluence of the East and West Branches in Hancock, N.Y., to the Delaware Bay.

Additionally, more than 400 miles of the River and its tributaries are designated as Wild and Scenic, garnering protections from the federal government from future development projects.

The Delaware River basin an economic driver for much of the region. The famed Upper Delaware wild trout fishery alone contributes more than $400 million to that region. In total, more than $22.5 billion is pumped into the regional economy from recreational activities, and that number continues to grow.

There’s still plenty of work to be done, though.

Since 2017, Congress has appropriated between $5 million and $10 million annually as part of the Delaware River Basin Restoration Program.

Trout Unlimited has been the benefactor of more than $969,000 of this funding, allowing us to carry out projects in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania to improve wild trout habitat and watershed connectivity.

We are thankful for this financial commitment, but we must continue to advocate for its growth into the future, securing clean water for recreation enthusiasts, businesses, and those who rely on the Delaware for clean drinking water.

TU Business member Ghostech Strike Indicators in Allentown, Pa., supports clean water funding in the Delaware River Basin

Earlier this year, New Jersey upgraded more than 600 miles of streams and rivers to Category 1, one of the highest levels of protection offered in the state. In Pennsylvania, the Fish and Boat Commission has been upgrading Class A and Wild Trout streams on a quarterly basis, and in the second quarter of 2020 alone, more than 1,200 comments were filed in favor of these stream upgrades.

TU members and supporters, in addition to restoring stream miles throughout the Delaware River Basin, have been vocal advocates in support of such efforts, helping to ensure that future generations can enjoy the recreational opportunities of the Delaware River.

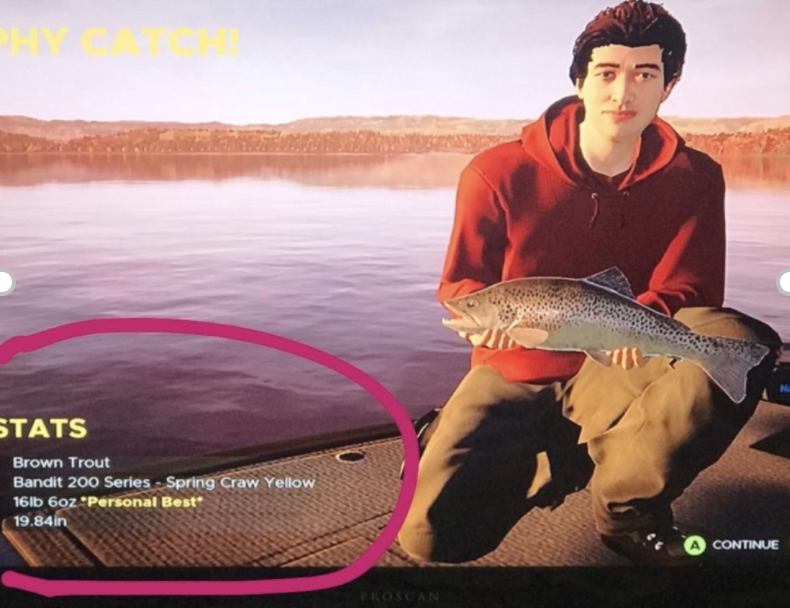

Rob Shane is the Mid-Atlantic Organizer for Trout Unlimited. He’s based in Carlisle, Pa. Despite being stuck at home this spring he managed to catch his personal best brown trout of 16 pounds, 6 ounces. (On his Xbox.)