Editor’s note: This column was originally published in the Washington Post on Sept. 23, 2019

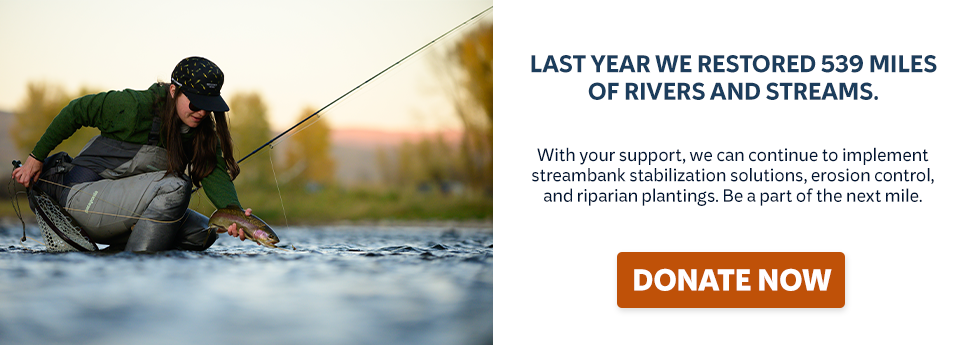

The announcement that the Environmental Protection Agency was scrapping Obama-era rules designed to protect small streams and wetlands made me recall a misty morning this spring on the Potomac River above Georgetown. I brought a striped bass, locally known as a rockfish, to the wooden rowboat. My friend, Mike, said, “15 pounds, every bit of it.” A nice fish made better by the fact it was caught from and released into the Potomac River in the heart of Washington.

Later, over the phone, my dad laughed when I told him the story. “When I went to school in Washington in the 1960s, you wouldn’t go near the Potomac, much less catch fish from it, for fear of getting sick.”

The Potomac, as with other urban rivers in the 1960s, was little more than a way to convey trash and pollutants downstream. In 1969, another urban river, the Cuyahoga, burned. The height of the flames on Cleveland’s river reached five stories. Today, thanks to the Clean Water Act, more than 60 species of fish inhabit the cleaned-up Cuyahoga River.

The Trump administration’s announcement puts at risk nearly 50 years of progress making rivers such as the Cuyahoga and Potomac more fishable and swimmable.

The Clean Water Act protects rivers in two ways. First, it regulates the discharge of pollution from factories, for example, into rivers. Second, it addresses secondary sources of pollution from development such as subdivisions, road construction and farming.

The Trump Administration has proposed to eliminate the protections of the Clean Water Act from small streams and wetlands that can be seriously affected by development activities.

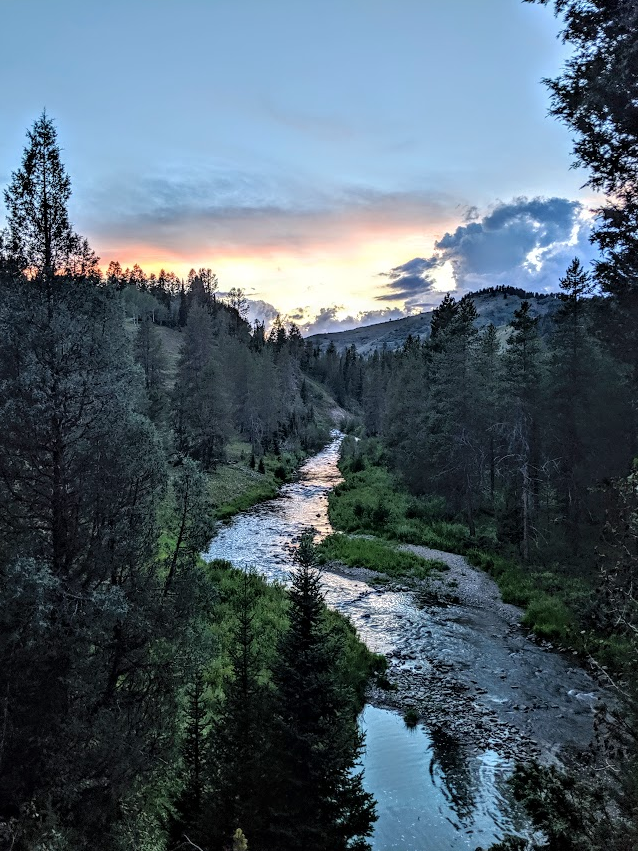

Every angler knows that gravity works cheap and never takes a day off. Everything we do in small streams will eventually be reflected downstream in the health of larger rivers and streams.

For 30 years, the Clean Water Act applied to small and large streams alike. In 2006, the Supreme Court decided that for the Clean Water Act to apply, small streams and wetlands must share a “significant nexus” with larger downstream navigable waterways. After a years-long scientific review, the Obama administration finalized rules in 2015 that demonstrated how water from small streams that may run dry during the year connect to downstream navigable waterways.

The Trump administration is proposing to replace these rules with ones that will not protect small seasonal streams and as many as 50 percent of the nation’s wetlands. The administration’s new rules could, for example, eliminate the need for landowners to get a permit before they build a road or store diesel fuel, chemicals and other waste in small, seasonal stream beds.

The United States has witnessed an explosion of natural gas development over the past 15 years. Many of the pipelines that carry the gas occur in small headwater streams. Since 1987, spills and accidents have occurred more than 3,200 times. How many more will occur if the oversight of the Clean Water Act is removed from pipeline construction in seasonal streams?

In arid states such as Arizona, the administration’s proposal could result in 84 percent of the stream miles losing protections of the Clean Water Act. In wetter states such as Maine, more than 60 percent of stream miles could lose protection.

The streams that could lose protection under the new Trump rules provide drinking water for more than 117 million Americans.

Thanks to the Clean Water Act, the story of river conservation in America is one of progress. Our rivers no longer burn. Sport fisheries abound in cities such as the District, Cleveland and New York. Drinking water filtration costs are lowered because of healthy headwater streams.

The Trump administration has said it will finalize its new rules within a few months. If you care about fishable, swimmable rivers that provide drinking water, now is the time to stand up for clean water.