The Klamath dam removal process is well underway and has received a lot of attention – both positive and negative. In some cases, outright misinformation has been spread by opponents of dam removal.

As this massive restoration project unfolds, it is a great moment to provide an update and highlight how extensive project planning has mitigated the temporary impacts to water quality.

Dam Removal: Process Update

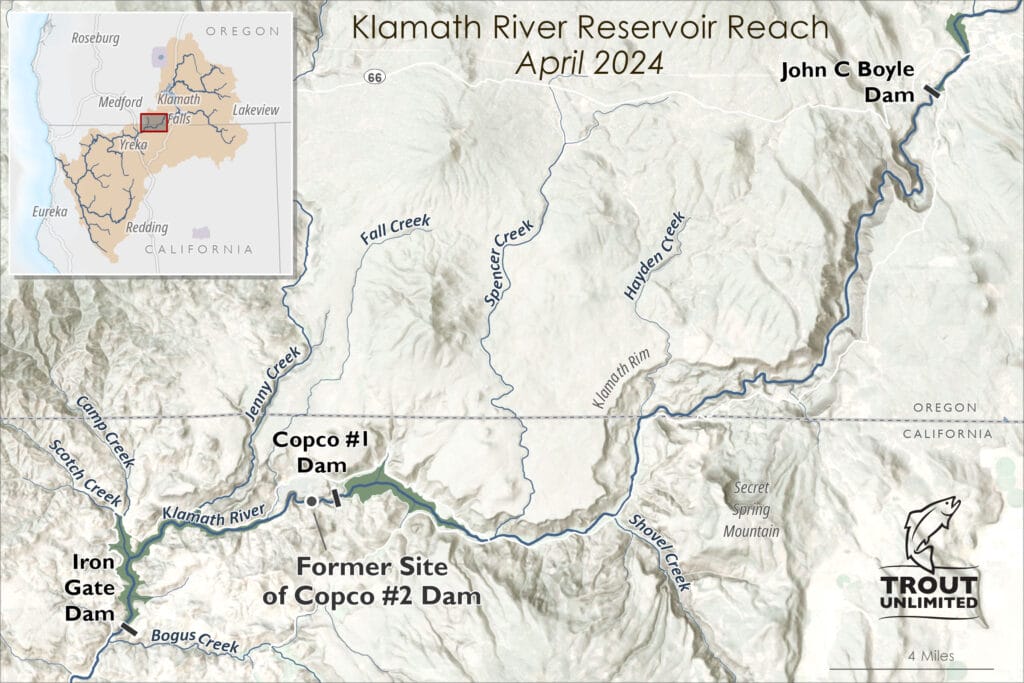

Of the four dams that are slated for removal in the Klamath River, the smallest one (Copco 2) was deconstructed last year. Below the former site, the river has returned to a 1.7-mile-long canyon that was dewatered when Copco 2 was built.

The reservoirs behind the remaining three dams (JC Boyle, Copco 1, and Iron Gate) were drained in a ‘drawdown’ process that began in January. At Iron Gate, an existing diversion tunnel through the base of the dam was opened for the first time since the dam was built. Explosives were used at Copco 1 and JC Boyle to breach a path for the water. As planned, the released water transported decades of accumulated sediment downstream from the former impoundments.

Immediately following drawdown, staff from the Yurok Tribe began planting native seeds and acorns in the dewatered reservoirs as a part of the planned revegetation effort. As those plants are established, they will stabilize the remaining reservoir sediments, preventing erosion and high suspended sediment concentrations in the future. Two months into the process, seedlings can already be seen growing in the former reservoirs.

Physical removal of Copco 1 has begun, ahead of schedule. All three remaining dam structures will be removed over the summer and fall.

Beginning in March, water was strategically released from the upstream Link River Dam controlling Upper Klamath Lake to create ‘flushing flows’ that will move some of the remaining reservoir sediments downstream. These flushing flows are timed to continue moving sediments while they are still wet and mobile, while also reducing impacts to fish.

While this forward progress has been cause for celebration, and has largely proceeded according to plan, it has also been a trying time for the Klamath River as well as the people and animals that call the Klamath home. As has been widely reported, the reservoir drawdowns led to sediment-laden water that smelled bad, was temporarily harmful to fish, and was unfit for human consumption, although it’s worth noting that there are no known people who would have been using raw Klamath River water for drinking water supplies.

Fish that lived in the reservoirs (mostly invasive Yellow perch and other introduced panfish) died when the reservoirs were drained. A small number of deer searching for water died while traversing the muddy, drained reservoir People whose property previously bordered a reservoir are temporarily bordering a mud flat. Two wells, including one shared drinking water well, ran dry. The Klamath River Renewal Corporation is providing temporary water and working with the affected homeowners on a permanent replacement.

As with other dam removals, such as the Elwha or White Salmon, this early period of dam removal is challenging. At the same time, a tremendous amount of behind-the-scenes planning has prevented or limited negative outcomes through this process, and I want to highlight some of these.

Reservoir Sediments

Releasing reservoir sediments into rivers is always a primary concern for any dam removal. Reservoirs intentionally slow river flow, which causes sediments to fall out of the water column and collect in reservoir bottoms. When the reservoirs are drawn down, these fine-grained sediments are carried into the river and can harm fish through gill damage, physiological stress (i.e., increased cortisol or decreased leukocrit), or hinder feeding and territoriality behaviors. Suspended sediments can also smother embryos and pre-emergent alevins in spawning redds or cause stress and impaired homing in adults. The harms of negative suspended sediments can be amplified when anaerobic bacteria are released with the sediments, causing large reductions in dissolved oxygen, or when stream temperatures are high.

Because reservoir sediments can cause so many problems for fish, an aquatic work group made up of the Klamath Basin Tribes, Klamath River Renewal Corporation, and state and federal natural resource agencies undertook years of extensive planning and analysis to identify prevention and mitigation measures for dam removal. The work was analyzed repeatedly for more than a decade, culminating with an extensive permit review by the State of California water quality regulators and the federal fish and wildlife agencies.

This review process imposed significant mitigation measures on the dam removal process. It concluded that while there would be significant temporary impacts, those negative effects would be greatly outweighed by long term improvements for fish and water quality.

Mitigating for Expected Turbidity

First, the United States Bureau of Reclamation conducted extensive testing of reservoir sediments and found the sediment to be non-toxic, mostly consisting of dead algae, fine clays, sand, and gravel. Of the chemicals detected in reservoir sediments, none were at concentrations high enough to cause adverse effects in exposed humans and wildlife. Arsenic levels and other heavy metals were consistent with naturally occurring background levels. These results meant that reservoir sediments in transit or distributed through the system were unlikely to leave behind toxic materials.

Next, reservoir drawdowns and pulse flows were scheduled for January through April to take advantage of the fact that most juvenile and adult salmon are not using the mainstem river during that time, hence avoiding the impacts of sediment releases. The majority of juvenile salmonids and Pacific Lamprey spend winters in the tributaries and most adult salmon and steelhead are in the ocean.

The exception are relatively low numbers of juvenile coho that overwinter in alcoves, side channels, and backwater floodplains along the mainstem river. To protect these fish, the Karuk Tribe fisheries department collected nearly 250 juvenile coho salmon between Iron Gate and the Trinity River confluence and relocated them to off-channel ponds that were not affected by suspended sediments.

Lost Hatchery Chinook

Releases of juvenile Chinook that were produced at the Fall Creek Hatchery were delayed until water quality in mainstem river improved to acceptable conditions, both in terms of suspended sediment concentrations and dissolved oxygen levels. These delays were planned and timed around both drawdown and pulse flows and are not expected to affect outmigration success or survival.

In early March, there was an unplanned mortality event involving hatchery fish released from the Fall Creek Hatchery. Approximately 830,000 fall-run Chinook salmon fry were released to make room for the remaining fish in the hatchery. The fry were released upstream of Iron Gate Dam and died of gas bubble disease when they passed downstream through the dam’s tunnel. Gas bubble disease is caused by turbulent and highly aerated water – not suspended sediments from the reservoir drawdowns. Although this was an unfortunate mishap, these fish were considered ‘extras’ and will not affect recovery goals or the releases planned later this year.

This incident highlights the challenges of managing fisheries in systems with dams and how important it is to remove the Klamath dams. The loss of hatchery fry received a great deal of attention, but the good news is that the dam removal process did not kill these fish: Downstream passage through Iron Gate Dam did – and very soon that migration barrier will be gone.

Short-Term Impacts Outweighed by Long-Term Restoration

While none of these mitigation measures will prevent all harms due to the temporary increases in turbidity, they do considerably lessen them. Additionally, it is important to remember that any harms caused by the sediment releases are short-term and relatively minor compared to the enormous and long-term damage caused by the dams themselves.

For over a century, the four lower Klamath dams blocked native fish from accessing over 400 miles of habitat in the watershed’s upper basin. The reservoirs caused toxic blue-green algae blooms that were harmful to fish and humans, as well as high water temperatures that contributed to outbreaks of parasites and bacteria that caused extensive fish kills. Sediment supply and transport was limited by the four dams, which reduced spawning gravels for fish and stabilized the streambed in a way that fostered large populations of the worm hosts for the fish parasite C. shasta.

So, while the dam removal itself is challenging and does have some negative impacts, they are a short-term cost for a much larger long-term gain. A free-flowing Klamath River is expected to maintain much lower water temperatures, limiting the growth of parasites and algal blooms. People will be able to safely swim in the river during the summer, which was previously not possible because of the poor water quality. Salmon, steelhead, and lamprey will have unobstructed access to upstream spawning and rearing habitat.

Final Thoughts

TU’s Brian Johnson has a unique insight into the work unfolding in the basin. In addition to leading TU’s efforts to restore a free-flowing river, Johnson is the President of the Board of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, the nonprofit created to take ownership of the dams, manage their removal, and restore the former sites.

“I especially appreciate Barry McCovey’s description of where we are at in the process,” Johnson explained. “A member of the Yurok tribe and their fisheries director, he recently told reporters: “the river is like the arteries of the earth, and the water would be the blood.” Barry likened the dams to blocked arteries that haven’t been able to convey nutrients or carry waste. Right now, he said, “the river is on the operating table getting those blockages removed.””

“Removing the Klamath Dams in an immense, and complex, undertaking,” Johnson continued. “The good news is that the project is running ahead of schedule and on budget. Years of planning, testing, and extensive engineering are proving their value. Turbid water, low dissolved oxygen levels, and wide expanses of mud in the drained reservoirs were predicted and well understood, and that doesn’t make it pleasant in the near term. It is dramatic, and difficult at times, but it is necessary step required to rebuild salmon and steelhead populations and vastly improve the river’s water quality in the future.”

Dr. Haley Ohms is a Salmon Biologist on Trout Unlimited’s Science Team. Her research is broadly focused on salmon ecology and her current projects include population-genetic models to study hatchery impacts to wild fish, juvenile dispersal as a mechanism for life-history diversity, and drought responses by California steelhead.