How many partners does it take to restore a salmon stream?

A conservation organization, a mining company, and the U.S. Forest Service sit down to plan a project . . .

That may sound like the start of a joke, but it is the reality behind the effort to restore a salmon stream in southcentral Alaska. A reality that came together out of ingenuity and a shared interest in caring for Alaska’s fish.

After working together on an annual Armed Forces appreciation fishing trip and being inspired by the great work Kinross Gold had accomplished with Trout Unlimited in the lower 48, TU’s Austin Williams and Kinross Gold’s Anna Atchison knew they had an opportunity to make a big impact in Alaska.

In the winter of 2020, Alaska staff members from both organizations got together and established the Alaska Abandoned Mine Restoration Initiative with the mission of restoring fish habitat degraded by historic mining. This unique partnership was the first of its kind in Alaska.

With the Initiative launched, all they needed was a project. They found it on Resurrection Creek in the Chugach National Forest, which provides important habitat for Chinook, coho, pink, and chum salmon, rainbow trout and Dolly Varden. Historic placer mining in the early 20th century straightened the river channel, removed important salmon spawning gravel, and significantly reduced critical rearing areas that salmon need to survive.

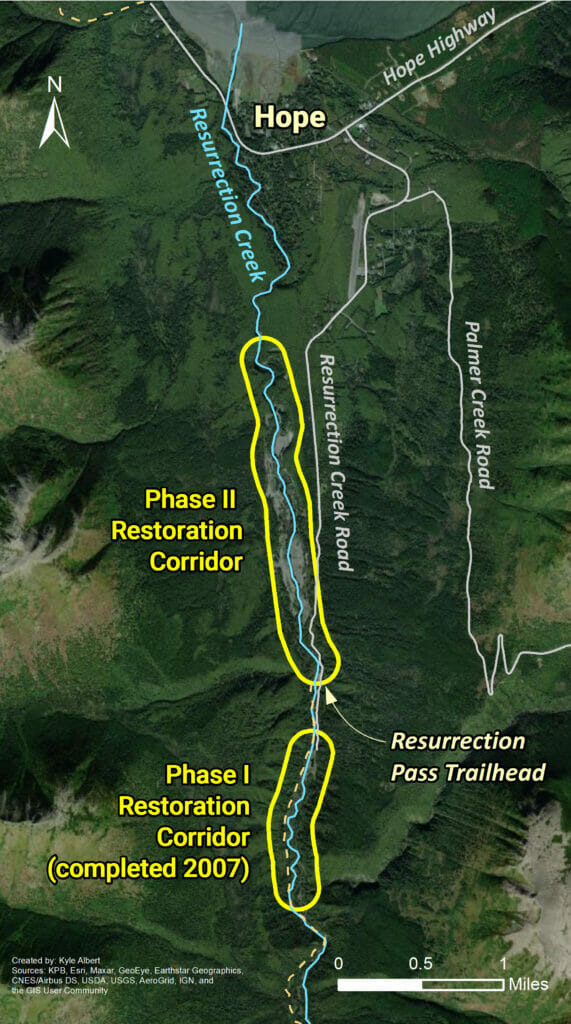

After almost a century of decimated salmon runs and other negative impacts to fish and wildlife, the U.S. Forest Service began restoring Resurrection Creek in 2002. Restoration was planned in two phases, and the first 1.5 mile of work was completed in 2006.

This project reconnected the historic floodplain, stream channels and riparian areas; constructed new pools, side channels and ponds; installed logs and root-wads in new stream channels; and re-vegetated the riparian areas. After completion, numbers of Chinook salmon increased six-fold and the populations of all salmon species in the creek continue to increase.

The success of this project made it apparent additional restoration would likely have similar benefits, and the Forest Service began planning for next phase along 2.2 miles of the lower stretch of Resurrection Creek.

The plan was there—but unfortunately the funding was not, and the project sat on the shelf for 14 years.

Enter the Alaskan Abandoned Mine Initiative. The second phase of Resurrection Creek’s restoration was selected as its first project. Kinross’ investment of more than $500,000 over three years helped leverage additional dollars from the state Alaska Sustainable Salmon Fund and the federal Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund, bringing the Resurrection Creek project back to life.

These are exactly the kind of projects that TU and our partners will be able to do more frequently in Alaska and across the West Coast, thanks to Congress’ allocation of an additional $172 million to the Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law last year.

A unique partnership between TU, Kinross, the Forest Service, the National Forest Foundation, and Hope Mining Company has coalesced to jumpstart the second phase of the restoration project. The project is slated to begin construction in early summer of 2022. Behind each organization’s participation in the project is a dedicated and passionate staff member who is willing to work creatively and collaboratively for the greater benefit of fish habitat.

Atchison is the manager of External Affairs for Kinross, and her role as a mom, miner, and life-long Alaskan brings a unique perspective to the table. She described the partnership as “having the courage and boldness to first see a need, be open to flushing out the need and viewing it from a perspective of common good, and then doing everything you can to address the need.” That vision and leadership helped launch the initiative.

Williams, who serves as the project leader for TU, knew the project would need more help to get it across the finish line. His experience as Alaska director of Law and Policy has shown him time and time again that collective impact is most achievable when working together. That meant bringing more collaborators to the team.

The National Forest Foundation stepped in to provide additional fundraising and project management support. The foundation’s Pacific Northwest and Alaska Program director Patrick Shannon knows the importance of this project, both to the natural world and to the surrounding community.

“The importance of salmon to ecosystem health and to Alaskans cannot be overstated. They are the lifeblood of many river systems and are a livelihood for many people,” he said. Patrick brings that appreciation for salmon, along with a wealth of experience in collaborative restoration projects, to the team.

This project begins and ends with the Forest Service. Resurrection Creek flows through land it manages, but it also flows through active mining claims. Forest Service hydrologist Angela Coleman works to coordinate restoration construction with the mining activities in the surrounding landscape by the project’s fifth partner, Hope Mining Company. She is a key member of what she describes as a “dream team.”

“This success is one built on the ability to find common values in unique partnerships and to collaboratively achieve common goal,” Coleman says “Our common goal is to see a fully restored Resurrection Creek that will provide habitat for robust fish and wildlife populations. Creativity, leadership, openness, respect, and trust are a few of the common values that are getting us to that goal.”

To tally it all up: We have a federal agency, two conservation nonprofits, a multi-national corporation, and a small private company all working together for the benefit of fish. Each partner fills a crucial role and brings important experience. Each is invaluable to the success of the project.

“Ten years from now,” Williams says, “Resurrection Creek will meander where it now runs straight, vegetation will be growing along its new banks, and with any luck large schools of young salmon fry will be seen finding refuge in calm water before their migration out to the ocean and back.” That is a future we can all get behind.