A volunteer helps expand Alaska’s Anadromous Waters Catalogue

I felt bad for the fish.

The fry were darting back and forth in a stagnant pond that was only a few inches deep, their infancy spent oblivious to the pristine waters for which Southeast Alaska is known. But that’s just me assuming what is beautiful to me would be the best option for the fish. There were no roaming predators in this pond. The outlet was densely covered by wildflowers and grasses that created a canopy so dense water was not visible.

So maybe I shouldn’t have felt bad for the fish. Maybe this was the optimal habitat for salmon in their youth—this trickle of water I would have overlooked was exactly the type of water the species needs. It was isolated and nothing about the modern world had encroached into this inlet. It had been used, but the use gentle. There were no docks, mooring buoys or pilings left from the days of commercial fishing. Nature had altered the landscape in this beautiful yet unremarkable inlet, not humans.

A closer look

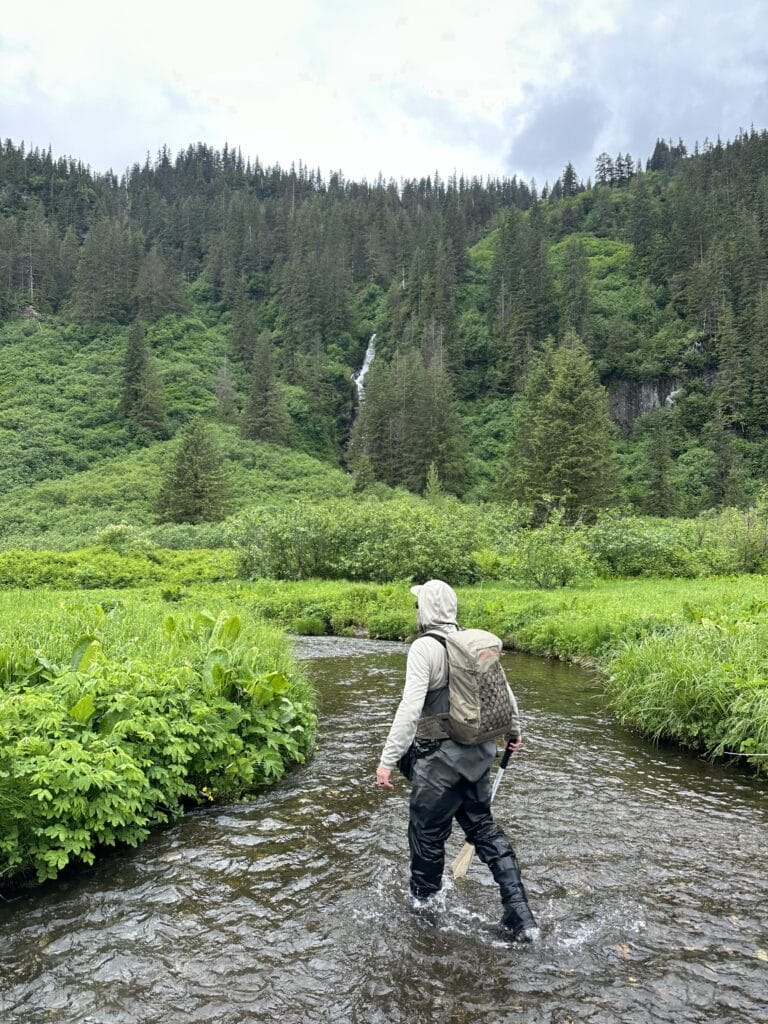

I was invited by Trout Unlimited to fly out of Juneau to a remote drainage that had a creek with known runs of coho, pink, chum and both Dolly Varden and cutthroats. There was another flow that ran parallel before joining a few hundred yards from the ocean, an afterthought since a tributary of a flow that only qualifies as a creek, not a river, isn’t often worth a lot of attention. Given the terrain, it looked like it was probably just a channel that separated from the creek higher in the drainage then rejoined it just before reaching the ocean.

But Mark Hieronymus wasn’t so sure. He pored over maps with the diligence that reminds you that not everyone has lost the drive to put pride into their work. He had been to the main creek before and wondered about the offshoot. This was his chance to find answers and potentially add this river and the species of fish that called it home to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s Anadromous Waters Catalog—a map of rivers that provides users with information regarding resources and fish with added protections.

Trout Unlimited’s Fish Habitat Mapping Project has worked to document previously unknown anadromous waters and species in Southeast Alaska since 2018. This project has added over over 96.5 miles of waters and/or species to the catalog since its inception, granting those species and waters the conservation measures they deserve.

While the five or six largest rivers in Southeast Alaska (and everywhere else) get the most attention, the average river in this region is only a few miles long. If this two-mile flow, fed by snowmelt that first cascades 2000 feet down a half mile of rocky chutes before settling into a flow, could be potentially used by salmon, it matters.

History didn’t bode well for fish

It’s been over a century since questions were asked about whether it was a good idea to treat rivers as endless and salmon runs as limitless. Even the most remote inlets in Southeast Alaska carry the leftovers of mining, logging and/or cannery operations that ruthlessly extracted throughout the late 1800s and into the mid-1900s before some semblance of order took hold. Arrogance and ignorance ruled the day. Even when it came to preservation. To protect the salmon runs, there was a bounty placed on Dolly Varden since their voracious appetite for salmon eggs was thought to be a threat to the survival of the runs. Nevermind that they had always existed.

But there was also a voice of restraint and an antidote to the ignorance of believing in infinite salmon stocks. Had there not been the White Act of 1924 which first set escapement regulations and the banning of fish traps in 1948, the crumbs we argue about today may have been long gone. Turns out saying no to a profit-at-all-costs mindset and getting in the way of progressing toward complete salmon annihilation was a very good, forward-thinking thing.

Small but mighty

As we continued up each little branch of the main creek, scooped up the feisty fry with our nets identified the species, marked the spot on the GPS then moved on, I couldn’t help but ponder this history. I went deep: What if the ancestors of this fish were from one of those rivers targeted by a cannery a century ago, whose mouth was nearly completely blocked by a fixed fish trap that would turn nearly the entire run into canned meals? What if the DNA is that of a school of fish that decided their river was ruined and it was best to find clean, obstruction free water? Had they strayed and found Afterthought Creek (my name for it) as ideal habitat tucked away from the historical commercial threats in the vicinity? Or had they always returned here, surviving the traps, nets, spoons, herring plugs, spinners, flies, orcas, sea lions, seals and whatever else in the big scary world that threatened to end them before they could return home?

I extrapolated the value of the thousands of small rivers in Southeast Alaska such as this that have small, feisty runs that collectively contribute a substantial number of salmon to the overall total. Small, fragile but vital.

I decided it was a little silly to be feeling sorry for a fish that is concerned more with the instinctual act of living. It’s a decidedly human thing to ponder things like comparing circumstances or wealth acquisition.

The water was unpolluted and perfect for its needs. What more could it ask for?

Jeff Lund is a freelance writer based in Ketchikan, Alaska. His column “I Went to the Woods” appears in the Juneau Empire twice monthly. His book, A Miserable Paradise: Life in Southeast Alaska is available in local bookstores and at amazon.com.