WEST BRANCH SUSQUEHANNA RIVER, NORTH CAMBRIA, Pa.

The angler stood in the shadows, peering intently at the water like a heron waiting for the moment.

Then the cast.

The line tightened.

Allison Lutz smiled, subtly, as she netted the 12-inch-long wild brown trout.

The smile was not so much about this individual fish. It was about the fact that this fish was even here.

A river’s resurrection

We were fishing in the headwaters of the West Branch of the Susquehanna River, not far from the small town of Northern Cambria. Here the West Branch — the simpler name most folks use — looks like just another of the many hundreds of Pennsylvania trout streams. It’s small water. Not small enough to jump over, but easy to cross in a pair of hip boots.

It’s not exactly packed with fish. Nothing like some of the state’s famous spring creeks that hold 2,000 or more wild trout per mile. But it holds wild trout, and that’s saying something. Native and wild trout are here, where they haven’t been for decades, and to locals and those who know the river, what it took for the populations to re-establish makes them even more impressive.

Fifty years ago, this river was essentially dead, its waters so wracked by abandoned mine drainage from old coal mines that it could not support fish life. Decades of effort and millions of dollars in investments have helped bring the river back to life.

“In the 1970s, the river had been essentially written off, thought at the time to have no realistic possibility of ever being able to support a fishery,” said Shawn Rummel, a lead science advisor for TU based in Pennsylvania.“ Now anglers are able to catch trout in the headwaters sections and bass and other species in the warmer water downstream.

The water quality in the river has gone from predominantly acidic to alkaline within a few decades. Historical coal mining, conducted from the late 1700s through the 1970s with little to no regulation, left a lasting negative impact on the landscape. Mining operations left behind more than 40,000 acres of unreclaimed and scarred mine lands and more than 1,200 miles of polluted streams across the West Branch watershed

The West Branch Susquehanna gets a long-term study

The condition of the headwaters region of the river was once so deteriorated that a 1972 study by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania essentially deemed the river a lost cause, because the acidity was too high.

Remediation efforts, including active and passive treatment of acid mine drainage, has been a key factor in the river’s revival, which has also benefited from the passing of time.

Fortunately, the recent Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, along with reauthorization of the federal Abandoned Mine Reclamation Fund, should provide a boost to remediation efforts across the West Branch and elsewhere in Pennsylvania. Together these programs will increase funding for abandoned coal mine cleanup in the state from approximately $65 million up to $245 million per year for the next 15 years.

At the end of 2020, Trout Unlimited released a report that highlighted just how far the river has come, progress documented by a series of extensive surveys on the watershed’s health conducted every decade since the early 1980s.

Pulling together what was called the West Branch Susquehanna Recovery Benchmark II study required thousands of hours of work in the field, and then hundreds more hours analyzing data. The work followed previous analyses that documented the river’s health and, in so doing, its gradual recovery.

To test water quality, staff from TU and other partners collected water samples at 110 sites throughout the watershed in 2017. Of those sites, 80 were replicated from a 2009 benchmark project. Thirty sites from designated Class A wild trout streams with no impairment were also added as reference sites.

“This was a significant effort that required several months of intensive field work followed by significant data analysis,” Rummel said. “The sheer volume of sites and information provides insight to the current state of the watershed and helps inform future restoration and conservation efforts.”

While overall improvements were not as significant as those documented between 1984 and 2009, several tributaries showed major improvement.

As would be expected, the streams that showed the biggest improvement have all benefited from AMD restoration work since 2009.

The combination of multiple land reclamation and treatment systems completed in these watersheds and others all add up to help improve water quality on the mainstem of the West Branch, too.

As water quality improves, life rebounds.

In 2019 the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC) electrofished five sites that had been surveyed for fish populations in the late 1990s and in 2009. The efforts turned up 31 species, an increase from 29 a decade earlier and just 24 in the first sample in the late 1990s. Wild brook trout were found at several sites for the first time.

Since the 2009 fishery surveys, nearly 26 miles of the mainstem and 10 historically AMD-polluted tributaries have been listed by the PFBC as having natural trout reproduction. Although the results are encouraging, when the West Branch and its tributaries are compared to similar watersheds that do not have a history of abandoned mine drainage, it becomes apparent that these waterways still aren’t reaching their biological potential. There’s still a lot of work to do.

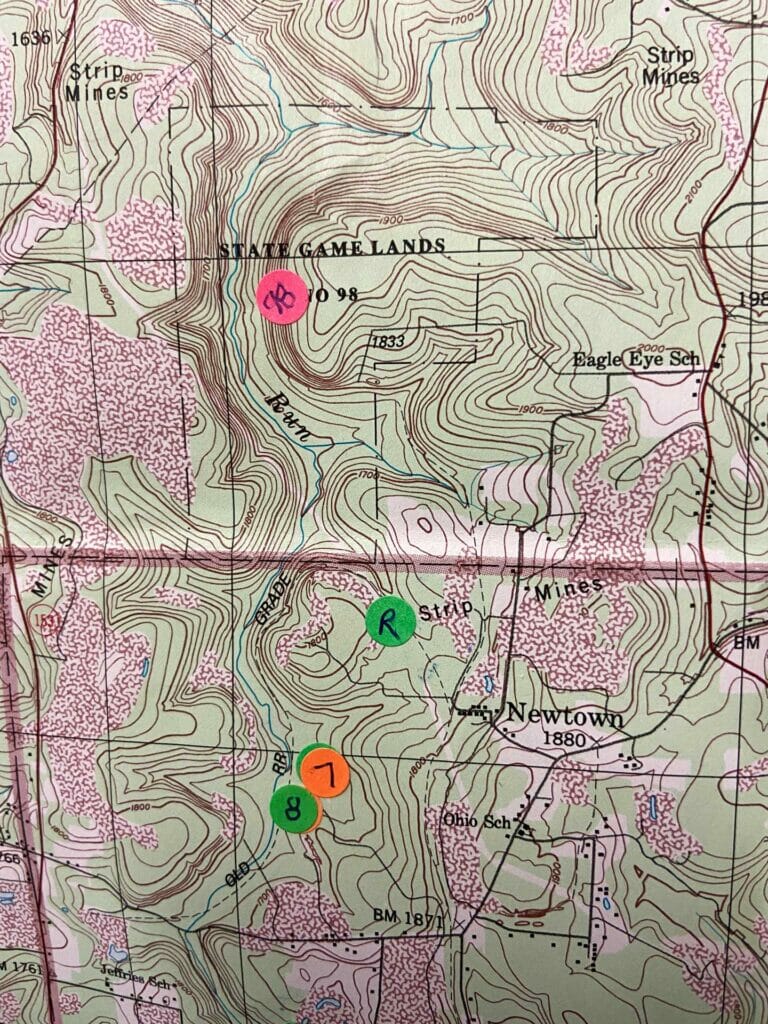

The day before Alison Lutz and I found those native brookies on the river, I spent a day with Lutz, Rummel and Kathleen Lavelle, a fellow member of Trout Unlimited’s staff in Pennsylvania, touring Clearfield County checking out acid drainage areas that remain troublesome.

Here we’d look at a small flow gurgling from a hillside into a three-acre pond of orange sludge on the riverbank. There we’d check out another creek that looked beautiful but was lifeless due to its extreme acidity.

“The landscape in the upper West Branch is very rural and mainly forested,” said Lavelle. “Some streams have a reddish orange or white hue and are obviously impaired even to the untrained eye.”

But, Lavelle pointed out, many other streams look pristine judging by the gin clear water. But clear water doesn’t always mean good quality.

“In some cases, streams can be so acidic the metals are dissolved so they may not appear obviously impaired at a glance, yet they contribute a tremendous amount of acidity and metals to the river,” Lavelle said. “When we were sampling previously unassessed streams in Clearfield Creek, a major tributary to the Upper West Branch, we found that if the stream wasn’t dry in the summer or impaired with AMD, it almost always contained native brook trout. There is tremendous potential in these robust populations between impaired streams.”

We also saw plenty of evidence of the work that has gone into improving the health of this critical watershed. Those tools include passive treatment facilities where abandoned mine drainage is directed through constructed wetlands and limestone-holding ponds.

And just that morning we had toured a massive active treatment facility just outside North Cambria.

The Lancashire No. 15 AMD Treatment Plant processes more than 10 million gallons of water a day. The water is pumped out of the deep mine into massive tanks where hydrogen peroxide is used to separate out the metals. From the scrubber tank it goes into a settling tank and then a pond before finally going into the West Branch clear and clean. (For an interesting summary of the operation, check out this PBS video.)

After walking over a scrubbing tank on a catwalk we all looked down to see that our shoes were orange with mist. Fortunately, like the water, the shoes could be cleaned.

Working to clean up streams polluted with abandoned mine drainage is not about quick fixes. Just ask Amy Wolfe, Director of TU’s Northeast Coldwater Habitat Program. She got her start with TU more than 23 years ago working in Kettle Creek, one of the major tributaries to the West Branch.

“I would always tell people that we celebrate recovery of mine-impaired streams in feet, not miles,” Wolfe explained. “But I’m really encouraged with the new federal funds coming to Pennsylvania and hope we can celebrate many more miles of restored streams in the coming years.”

Wolfe also hopes this will set the stage for support from members of Congress for Good Samaritan legislation so we can really make a difference on the ground without having to worry about liability. Long-standing issues regarding liability under the Clean Water Act often deter Good Samaritans – entities like TU and government entities that just want to restore our streams and rivers but had no involvement in creating the pollution in the first place – from engaging in abandoned mine treatment projects. Read more about TU’s efforts on Good Samaritan legislation here.

Fish!

The Pennsylvania crew had reached out to their network of sources to ask about fishing and gotten some intriguing intel.

One of them was Dan Collins, a 24-year-old fishing guide who grew up in Clearfield County. He was fortunate enough that by the time he began fishing seriously, things were already on the upswing on his home river.

“I grew up fishing the West Branch and I love bragging on that river,” said Collins, who did a stint as a TU intern in 2017. “I love going there because it’s not beat to death like some of Pennsylvania’s other rivers.”

Collins said he has had great days trout fishing on the upper West Branch, with some days catching dozens of fish. Fishing for smallmouth bass has also improved downstream.

“When I started fishing it we rarely caught anything larger than a pound and a half,” he said. “Now we’re getting 4- and 5-pounders.

“We never saw that 10 years ago.”

Smallmouth would have to wait for another trip. Our focus was on those trout in the headwaters.

“Knowing where the trout are is only one part of the battle,” Lutz said with a smile. “You never know whether they will eat or not.”

Lutz is one of those no-nonsense anglers, so she was on the water and casting before Rummel — another avid trout-chaser — and I had our waders on. Though we all had some chasers and lookers, Lutz’s colorful brown was the only fish at that first spot, so we started working our way north along the river, stopping at likely spots.

At one, we walked over a bridge that spanned the river, which by that time was probably 30 feet wide. The stretch has benefited from an extensive habitat-enhancement effort, with large logs placed strategically in the stream to create holding deeper scour pools and holding cover. The wood additions also catch and hold falling leaves and other organic material that, as it decays, provides the foundation for a healthy population of macroinvertebrates.

Phil Thomas, a TU restoration specialist based in Pennsylvania, said there have been multiple habitat projects in this section covering miles of stream over the past decade. TU was the lead on one project and heavily involved in another. Most have been undertaken by the Clearfield County Conservation District and the PFBC.

“The county conservation district and the PFBC have been instrumental in the habitat recovery of the West Branch,” Thomas said.

The work not only helps the stream, but the local economy.

“The vast majority of these use local contractors and locally sourced materials,” said Thomas, whose team is starting another project — this one a 70-structure habitat project on 2,500 linear feet of the West Branch near Barnsboro — in late September.

As we stood on the bridge scanning the stream from above, we spotted two nice trout, the largest a brown that looked to be about 18 inches long, finning in the clear water below. Key word: clear. The shallow water was going to make it tough for a good presentation and, sure enough, none of us were able to elicit a strike.

“Knowing where the trout are is only one part of the battle,” Lutz said with a smile. “You never know whether they will eat or not.”

At the next bridge Rummel and Lutz headed downstream. I walked a road upstream and cut down to the water a quarter mile away.

The water looked amazing, with a perfect run-riffle-pool make-up. The kind of water where you expect a strike on every cast. It wasn’t quite that easy but finally I saw a fish dart out from behind a rock and slam my streamer. The brown was probably 15 inches long, fat and healthy.

As I released the fish after a quick photo, I found myself smiling subtly. Not about that particular fish, but about the fact that it was there in the first place.

Comments