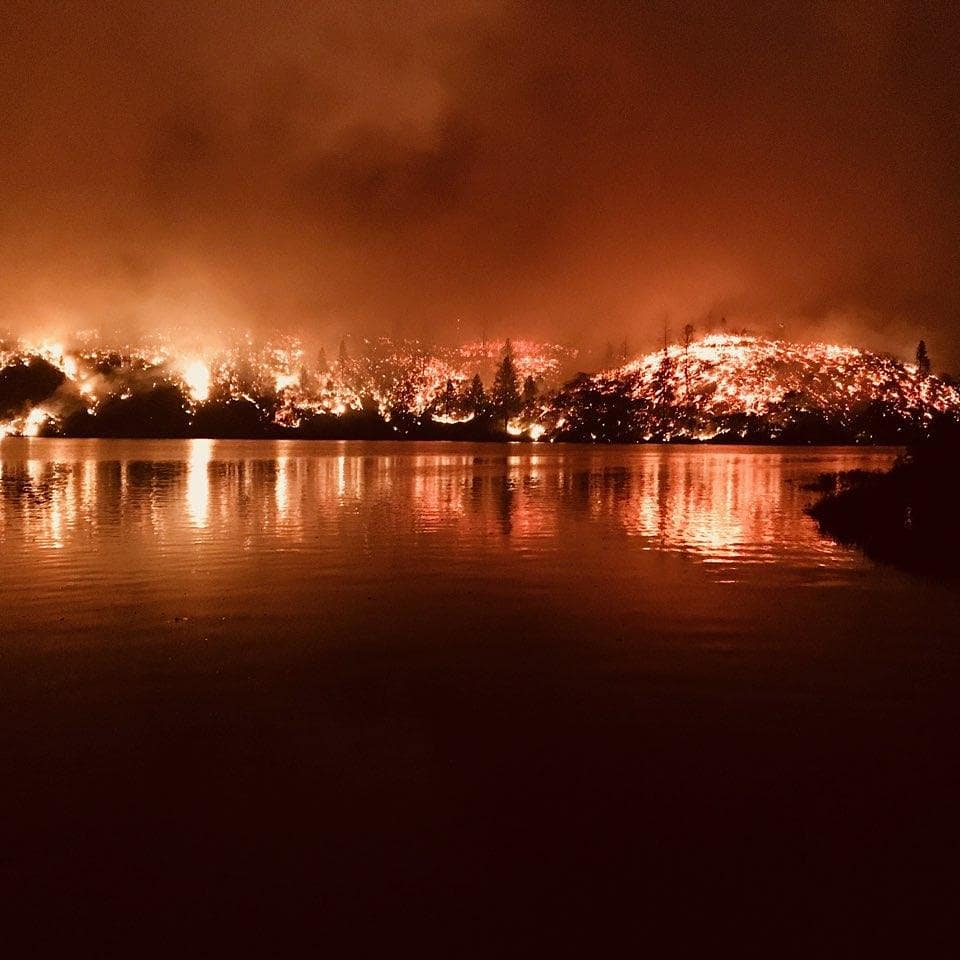

People all around Oregon woke on Sept. 8, 2020, to high winds, extensive power outages and lots of speculation by foresters that it could be the worst day of fires in Oregon’s history. That’s exactly what it turned out to be for Chrysten Lambert, TU’s Oregon director for Western Conservation, and many others when three wildfires whipped through the area in a split second and destroyed uncountable homes, devastated wildlands and severely impacted sensitive watersheds.

Fire’s destruction

Chrysten’s first concern turned naturally toward her children and family. Their family ranch sat in the bullseye of the 242 Fire that started at a campground the prior evening, spreading quickly in the high winds. At midnight, at the urging of the local sheriff, her mom quickly rounded up the horses, opened the gates for the sheep and cattle and fled to safety herself. By 8 o’clock the next morning, mercifully, the winds had shifted and saved their two homes and barn, but extensive damage was done to Klamath Agency buildings also on the property. In all, 15 historic structures burned, including one housing a charter school.

Sept. 8 was also her kids’ first day of school for 2020, and although it would be only online due to COVID-19 closures, there was natural excitement. But it quickly turned chaotic as the Almeda Drive fire began across the street from their home and just a few blocks from the elementary school where teachers hosted their virtual classrooms. Children began to drop offline quickly as the fire department went door to door evacuating families. Soon the entire Rogue Valley was engulfed in fear as the fire spread rapidly through neighborhoods and small towns of Talent, Phoenix and the northern part of Ashland destroying the homes and businesses of so many residents, but luckily sparing Chrysten’s family.

The 242, the Almeda Drive and Santiam fires, along with others in the state, combined to burn over 1 million acres and saw well over 4,000 structures lost. It certainly was the most destructive wildfire season in Oregon history. But that just meant more collaboration and work had to be done with federal and state agencies, timber companies, private landowners and conservation groups like TU.

Next steps

Chrysten’s family quickly got to work. A few small spring fed creeks on their property had severe damage. Because they are cold, clear tributaries to Upper Klamath Lake, they are vital to its health and therefore the health of native redband rainbow trout. After a highly successful spawning year in these tributaries, they knew restoration needed to happen quickly to create the spawning refuge for this important species. Her dad managed sediment control last fall, and with both federal and state assistance and donations of seeds, they were able to quickly revegetate the burned areas. But an Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife biologist called her to alert her family to bright orange runoff coming from salvage timber operations upstream just recently.

With that, Chrysten and her counterpart in TU’s Angler Conservation Program, Dean Finnerty, set out to work collaboratively with the state, timber groups and others to see what could be done both about the immediate aftermath from these fires but also with long-term goals in mind to improve forest and watershed resiliency.

Better management of salvage logging to leave wood and materials on the land and reduce road development is critical, continuing active forest management and prescribed burns to reduce risk to watersheds and communities is a piece of the solution, and reconnecting our streams to their floodplains can support the dual objectives of forest and river health.

All of this will take time, but as the state grapples with an even more severe drought in 2021 few other endeavors are more important.