Public Lands support the underlying spirit of traditional bowhunting and fly fishing

As trout season draws to a close in Michigan, the leaves change hues and, for many of us, our attention turns to antlered pursuits with the opening of archery deer season. Out West, hunter-anglers have been pursuing elk for almost a month already, so many anglers’ attention has already shifted.

For a few of us, the tools and the quarry change but the underlying spirit of the chase does not, nor do the public lands that support it. As I’ve been accelerating practice with my vintage recurve bows, I’ve noticed that I’m not alone in the dual pursuit of traditional bowhunting and fly fishing, dating back to one of TU’s more famous organizational founders.

A bit of TU history

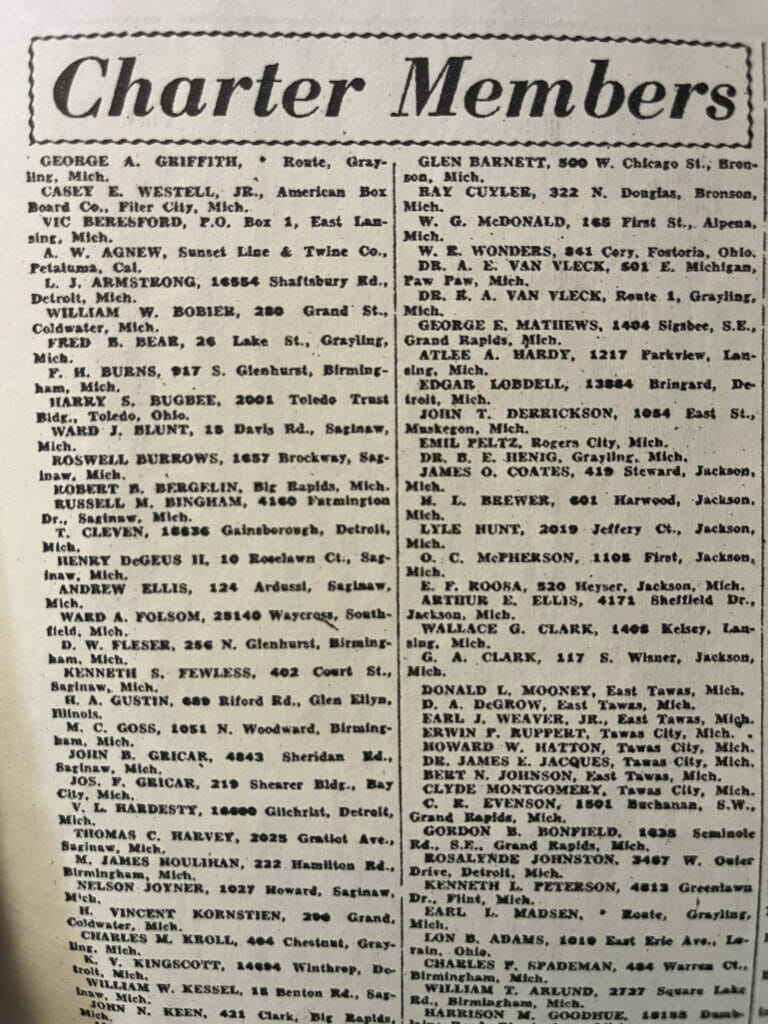

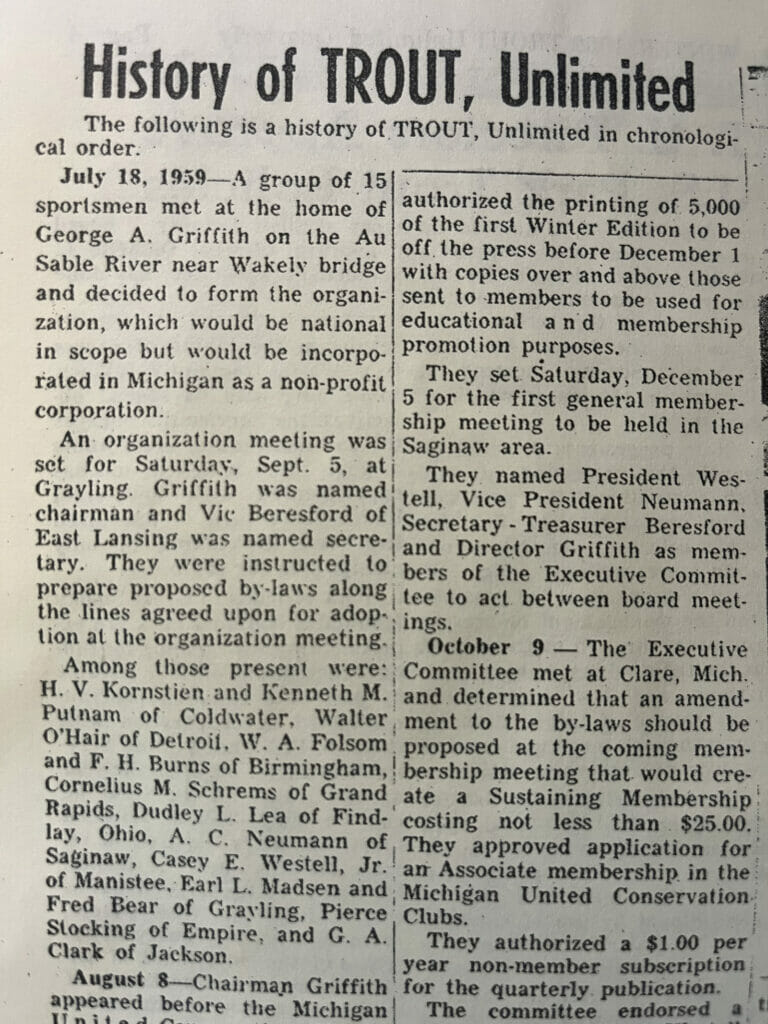

Trout Unlimited was founded in 1959 on the banks of the Au Sable River in northern Michigan when 15 fly anglers gathered at the cabin of George Griffith to form an organization to advocate for wild trout. One of those men was Fred Bear, the legendary bowhunter and founder of Bear Archery, then located in Grayling, Michigan. While known for his bowhunting exploits, Bear was an avid fly angler who spent time and eventually had his ashes spread on his “Grousehaven” property on the Au Sable River. The first issue of TROUT, Unlimited Quarterly listed Bear as a Charter Member, and Bear Archery placed an ad advising readers to “Limit your kill – DON’T kill your limit.”

Bear hosted a television show called Fred Bear’s World of Adventure which showcased bowhunting all over the world. Many of these adventures took place on public lands in the Rocky Mountain West, or Alaska, depicting hunters camping out of a canvas tent and often breaking out fly rods to catch dinner from a nearby stream. This marketing helped grow the bowhunting industry and create the market for his bows, but it also introduced fly fishing to many of those who watched it.

Both offer intimate pursuits

It should be no surprise, really, that the primary promoter of bowhunting at the time would espouse a message of placing voluntary limits on your kill. Long before compound bows were invented and crossbows added to archery seasons – before lighted sight pins, range finders and trail cams – bowhunting was a close-range pursuit done with a piece of wood bent by a string to propel a sharp point. It was a voluntary limit on the sureness of success requiring close range and a time-developed skill to accurately place the arrow. And for today’s traditional bowhunters, it still is.

“Traditional archery and fly fishing are intimate pursuits,” said Michael Salamone, fly fishing guide and angling columnist for Vail Daily. “Both require mastery of skills and enhanced knowledge of the environment to be successful. And both have self-imposed restrictions that we as anglers and archers embrace.”

It is not much different than choosing a fly rod over a spinning or baitcasting rod. Both tools put the hunter or angler within the range of perception of the trout or deer, requiring stealth. Both eschew the longer range made possible by a spinning or baitcasting rod, or a compound bow, crossbow or rifle.

“I always thought of fly fishing as the angling equipment of archery; archery during the long bow and recurve bow era, before compound bows arrived on the scene,” said Todd Tanner, founder of the School of Trout, in an interview with Hatch Magazine.

Finally, each can entice their adherents down bottomless DIY rabbit holes that begin with fly tying and arrow building – united by feathers – and progressing to rod building and tillering a selfbow. I recently shot a field course with my friend John Cleveland, who makes his own takedown recurves and his own arrows. He also ties his own flies and gives fly casting lessons at our local fly shop. For him, it’s all part of the same lifestyle, rather than separate pursuits.

Maybe the aesthetic qualities of a finely sculpted traditional bow riser and a vintage bamboo fly rod appeal to the same eye. For me, they also feel more like I’m playing an instrument rather than operating a contraption. Fly rods and traditional bows elicit the souls of their sports.

David Petersen might have put it best, writing in his book of hunting essays, Heartsblood: “Traditional archery is to hunting as fly casting is to fishing—each is the quietest, most artful, most personal and engaging expression of its genre.”

Public Lands offer places of deep immersion

Blue-lining a remote forest stream, trying to stay in shadows and cover, to get a close fly cast to a pool suspected of holding brook trout, searching for a flash of white on the crest of its fin, or the glint of sunlight flashing off its side, delivers the same instinctual rush I get when still-hunting with a recurve, trying to keep in shadows and downwind of cover that may hide the lateral line belying a bedded doe, or the glint of sunlight off the tine of an antlered buck. And our public lands support both; the location where I caught my first brook trout on a fly decades ago is less than a mile from where I set up a wall tent for deer camp each November.

Soon I’ll put away my trout rod until Spring, and in a couple months I’ll get serious at the vise about re-filling my fly boxes. In the meantime, though, I’ll be stalking the public land forests through which my favorite trout streams flow, stick and string in hand, in pursuit of venison for my freezer, bucktails for my Clousers and Deceivers, and the deep immersion as a participant in nature that, like fly-fishing, I get through traditional bowhunting.

Thanks to Fred Bear and others for setting the proper stage to engage in both meaningful pursuits on public lands.