After a final trip to hunt Gambel’s quail in Arizona’s Tonto National Forest in February, another hunting season ends.

Once shotguns and rifles are given a final cleaning all that remains is storytelling with family and friends. This is often done around backyard barbeques and the dinner table over delicious meals of wild duck, quail, mule deer and elk. This routine has become ritual over the years and is one I relish.

This routine, and the lifestyle on which it is based, depend on America’s incredible system of public lands, managed by agencies like the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and U.S. Forest Service (USFS). Access to public lands is why I chose to move to the American Southwest 25 years ago. It is where I will remain as I have become partial to this region’s rivers, mountains, deserts and fishing and hunting opportunities.

An elk hunt on sacred grounds

My favorite story from the 2024 elk season is an October hunt in Utah’s Bears Ears National Monument, located in the San Juan hunting unit. It took several years to successfully draw this elk tag, but it was worth the wait. I spent four days in the backcountry, encountering more elk and deer than fellow hunters.

The Manti-La Sal National Forest manages this part of Bears Ears National Monument.

On all federal lands managed by the BLM and the USFS, including national monuments, fish and game populations as well as fishing and hunting regulations are managed by state wildlife agencies. In Bears Ears, that means I have the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources to thank, as well the Forest, for this premier hunting experience.

Antiquities Act at work around the country

Bears Ears National Monument was established in 2016 through the Antiquities Act. This landmark law, written by a Republican congressman from Iowa and signed into law by Republican President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, has been used by eighteen Presidents—nine Republicans and nine Democrats—to permanently protect some of our nation’s rarest and most extraordinary landmarks, landscapes, historic and cultural values—and world-class fishing and hunting opportunities.

Places like Browns Canyon National Monument in Colorado, which includes a stretch of the Arkansas River—a Gold Medal trout stream and one of the best trout fisheries in the southern Rockies. Or the recently designated Sáttítla Highlands National Monument in northern California, which is the source of clean, cold water to the Fall River, California’s largest spring-fed river and a famous trophy trout fishery in which a unique strain of native rainbow trout has evolved.

In these locations, locally-driven legislative proposals to conserve these areas languished in Congress for years–sometimes decades—despite overwhelming support from hunters and anglers, local governments and affected stakeholders. Faced with Congressional inaction, the Antiquities Act provided a path forward to conserve important fish and wildlife habitat and quality opportunities for hunting and fishing.

Trouble for the Act

America’s public lands and the sporting opportunities they support are under increasing pressure from loss of habitat, resource extraction, drought, rapid growth in outdoor recreation and other influences. These conservation challenges require us to have all policy tools available to help balance multiple uses on public lands, including conserving fish and wildlife habitat.

Despite being an important tool for conserving fish and wildlife and sporting opportunities, the Antiquities Act and national monuments are not without controversy. Currently, Congress is considering the Ending Presidential Overreach on Public Lands Act, a bill that would require congressional authorization to establish national monuments. Doing so would effectively do away with the Antiquities Act altogether.

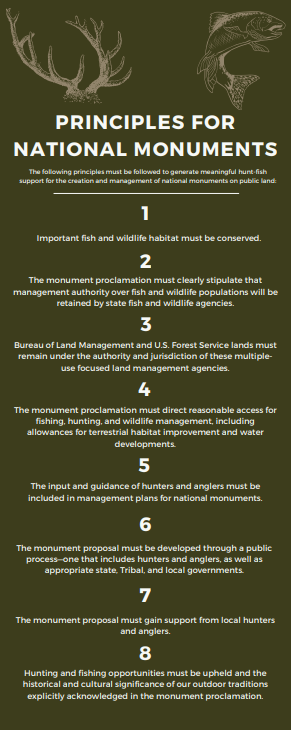

The Antiquities Act is a powerful tool for conservation and like any tool it must be used responsibly (see Principles for National Monuments), but it’s a tool that we would do well to keep in the toolbox for when Congress is unable to make good on locally supported conservation initiatives.

There is no productive fishing or hunting without productive habitat—and we have lost immense habitats over the past 150 years. Around the country, national monument designations made by both Republican and Democrat presidents have helped protect some of our best remaining hunting and fishing habitats and sporting opportunities.

Four years after signing the Antiquities Act into law, Theordore Rosevelt said that “the nation behaves well if it treats the natural resources as assets which it must turn over to the next generation increased and not impaired in value.”

Keeping the Antiquities Act as it is will help us heed Roosevelt’s call and keep America’s public lands a great place to hunt and fish.

More information on the Antiquities Act and fishing and hunting opportunities national monuments offer is available in National Monuments: A Hunting and Fishing Perspective.