As the Klamath River is reconnected, Chrysten Rivard reflects on the partnerships and dedication guiding TU’s work for the basin’s fish, water and communities

Salmon, steelhead and lamprey have been absent from the Upper Klamath Basin for more than 100 years.

As we ready ourselves for their return to the cold, spring-fed tributaries and headwater streams above the four dams removed this past year, I cannot help but reflect on the journey that brought us to this incredible moment—and on the hard work that is still to come.

How we got here and where we’re going

The reconnection of the Klamath Basin, the largest river restoration project in history, is happening thanks to the tireless advocacy of the Klamath Basin’s tribes, the leadership of at least six governors of Oregon and California, federal administrations led by both Democrats and Republicans, and the anglers, conservationists and countless individuals who understood that without healthy rivers and fisheries, the people of the Klamath Basin cannot thrive.

As our colleague Brian Johnson reminds us, the advocates for dam removal simply never gave up, no matter how long it took or how many obstacles were in their way.

Upstream of the dam sites at the center of that effort, TU and our partners spent years working to restore habitat and water resources for the basin’s communities and native fish. Now, with the historic opportunity to rebuild populations of returning anadromous species at hand, we are working hard to expand the scale and impact of this critical work throughout the Upper Klamath.

Shared Values

My career in the Klamath Basin began in 2002, on the heels of the devastating salmon kill on the lower river.

Traveling around the watershed at that time, I saw many streams highly impacted by more than a century of beaver trapping, timber harvest and cattle grazing in riparian areas. While there was some great habitat remaining in the Upper Klamath, too many streams were shallow, full of sediment, and way too wide. In many places the banks were grazed down to dirt, the once robust forests of willow trees were nearly gone and there was little cover for fish.

Elsewhere in the Upper Basin, tens of thousands of acres of riparian and lake fringe wetlands had been diked and drained, eliminating their ability to filter nutrients and sustain ecological diversity.

Working with a handful of members of the ranching community, we formed a small, local organization dedicated to finding a better path forward, one that could sustain agricultural operations while using less water and restoring habitat for fish and wildlife.

Our small group collaborated with biologists, ranchers and foresters to help build new restoration and economic models. We learned from members and staff of the Klamath Tribes, who have cared for these lands and waters for thousands of years. We worked with state and federal agencies to bring programmatic support to accelerate the pace and scale of restoration.

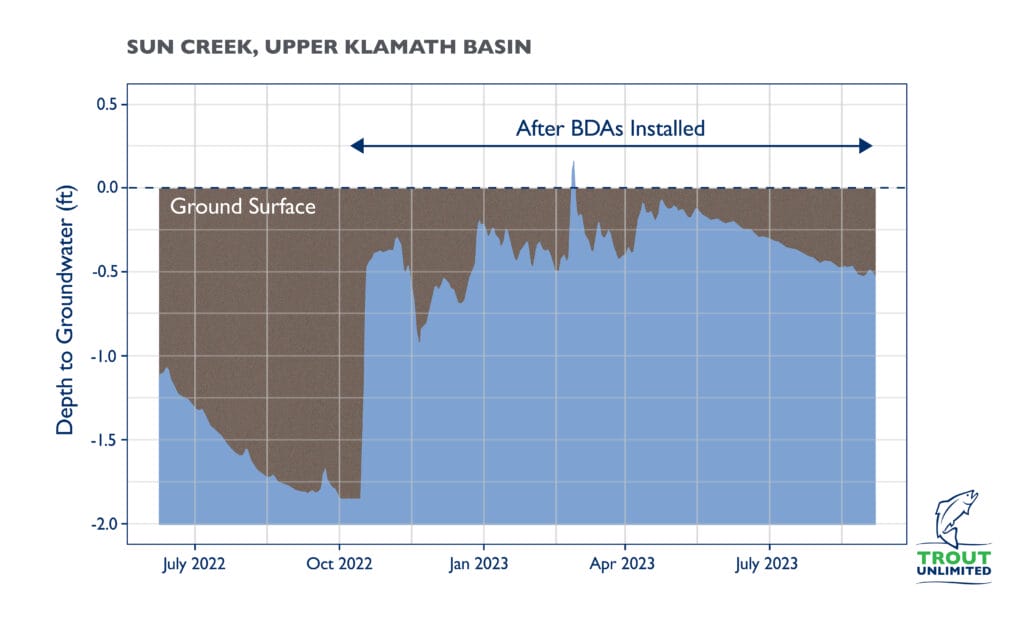

Over time, we watched the creeks narrow and the riparian vegetation grow back in the places we had worked. We saw our work to reconnect floodplains and bring beavers back to the landscape start to succeed, and we saw fish move into and utilize restored habitats.

Importantly, we learned that our partnerships were most successful when we worked to build trust, listen to diverse perspectives and understand each other’s needs.

In 2015, the Klamath Basin Rangeland Trust merged with Trout Unlimited.

Expanding the scale of restoration

Originally, our restoration efforts focused on improving habitat and water quality for the Upper Basin’s endangered Bull trout, native Redband rainbows and C’waam and Koptu, two species of endemic suckers native to Upper Klamath Lake.

While those species remain important, we always knew that much of this restoration work could eventually benefit anadromous species if the watershed was reconnected. As negotiations and agreements began to clear the way for dam removal, we redoubled our planning efforts to prepare for the fish to return. Today this effort is led by an incredible team of restoration practitioners that bring engineering, biology and chemistry expertise to implement our work. TU staff in the basin include Nell Scott, Charles Erdman, Tommy Cianciolo and Evan Bulla, each of whom bring an unparalleled level of technical skill, dedication and creativity to their projects and partnerships.

As our instream habitat restoration projects continued, TU staff also spent two years working with the NOAA Restoration Center and the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission to create the Klamath Reservoir Reach Restoration Plan. This public resource maps and prioritizes the restoration opportunities that would have the most impact in the portion of the watershed impounded by the dams, which is also expected to be some of the first reconnected habitat utilized by salmon, steelhead and lamprey. We are proud to be a part of the broad partnerships implementing this restoration work in the coming years, including work with the Yurok Tribe, and private landowners and timber companies.

To learn how Spring Chinook could move through historic habitat above Upper Klamath Lake, we partnered with Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, NOAA, the Klamath Tribes, private landowners, and researchers at the University of California-Davis to release juvenile fish tagged with transponders to track their migration from multiple tributaries throughout the basin. This work will help inform and prioritize our restoration strategies for recovering the once robust populations of Chinook to the upper basin.

Recognizing the critical role that private ranch and timber landowners play in the uppermost part of the watershed, we recently formalized our partnership with the Upper Klamath Basin Ag Collaborative and are implementing coordinated floodplain and aquatic habitat restoration projects with this important community, as well as building a new incentives model to meet the economic needs of agricultural producers. Together we plan to implement restoration projects across many miles of the Sprague River Basin, a key Klamath tributary, in the next few years. We have already completed 10 miles of that work during the last two years.

We also know that two major dams remain in the basin, Link River and Keno Dam. Both have fish ladders. While fish can migrate upstream and downstream past Keno, the current fish ladder does not meet state or federal fish passage standards. In the long run, it needs to be improved. That is why TU is working with the Tribes, state and federal agency partners, and irrigators that divert water from Keno to assess fish passage alternatives at this site, including removal of the dam, while maintaining essential services for irrigation and flood control.

Looking ahead

Today, as we celebrate the free-flowing Klamath River, we also recognize how much more work there is to do and how many partners we will need to be successful.

TU staff are committed to assuring that all the potential benefits of removing the four hydroelectric dams on the Klamath River are fully realized. Over 400 miles of historic habitat for steelhead, salmon and lamprey lie above the former dam sites.

We know that there is a way forward that can restore critical habitats for fish and wildlife while sustaining a strong and viable agricultural industry, providing climate and wildfire resiliency and importantly, working toward environmental and social justice for tribal communities. We know because we have been doing it already, seeing the results on the ground and are actively scaling our efforts to meet this moment.

With the support of our donors, members and many partners, TU is committed to providing unencumbered fish passage and connectivity to the habitats in the Upper Basin; to protecting fish from entrainment in the many unscreened irrigation diversions that remain in tributaries; and to restoring floodplain connectivity and riparian health across the watershed.

Trout Unlimited’s largest office in Oregon is in Klamath Falls. We have been committed to the restoration and reconnection of the Klamath Basin for decades. We are looking forward to continuing and expanding this work and the partnerships that make it possible because we are confident that restoration of the upper Klamath Basin will provide the greatest possible return on investment for wild, native fish, cold, clean water and the communities that depend on both.

Learn more: Visit Klamath River: Reconnection and Restoration to explore a new StoryMap of the dam sites and watershed, a timeline of the quarter-century effort to reconnect the basin, and resources for TU members and supporters to understand the intertwined story of the long road to dam removal and the restoration work underway upstream in the Klamath’s tributaries and Upper Basin.