California’s golden trout persist with project help from TU.

Golden Trout Creek

An angler since she was four years old, even after a long day working in the backcountry, Trout Unlimited’s Jessica Strickland couldn’t resist the opportunity to fish an iconic stream winding its way through a mountain meadow.

In September, during the last weeks of the fieldwork season in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains, a group of TU staff, ecologists and U.S. Forest Service staff left Horseshoe Meadow and hiked 10 miles further into the Golden Trout Wilderness to reach the Big Whitney Meadow complex. The team would spend multiple days mapping and planning in Big Whitney, but a few couldn’t wait until the morning to see it.

That evening, Strickland and a handful of folks hiked an additional two miles to fish on Golden Trout Creek. In narrow runs and pools, native golden trout snapped at dry flies. Gently cradled in her hands, the wild fish glowed in the evening light.

Like most of the habitat across the California golden trout’s native range, this remote landscape shows evidence of historic land uses that changed riparian vegetation. This degradation is what TU’s Golden Trout Project is working to repair on a new scale. After years of planning, TU and a dedicated network of state, federal and private partners are launching an ambitious effort to protect and restore the remaining habitat of California golden trout.

California Golden Trout

Though populations have been stocked throughout the American West and into Canada, the California golden trout’s native range is limited to less than a 600 square mile area high within the headwaters of the Kern River watershed in the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains. This includes a substantial portion of the South Fork of the Kern River and its tributaries, and an upper portion of Golden Trout Creek and its tributaries. Over the years the fish have lost access to large portions of their native waters, but much of what remains connected are encompassed within the Golden Trout Wilderness, a protected backcountry portion of the Kern Plateau spanning the Sequoia and Inyo National Forests.

An undeniably beautiful fish, golden trout retain parr marks and are thought to have developed their remarkable gold coloration as camouflage in the bright streambeds of decomposed granite found in the Sierra Nevada. At such high elevations, growing seasons are short and golden trout tend to be small fish. A 10-inch wild golden trout in its native range is a trophy.

Today, native golden trout populations are small fractions of their historic numbers due to compounding threats. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, sheep and cattle were grazed in Sierra Nevada meadows. The animals devoured vegetation, wallowed in creeks and trampled streambanks. Historic mining and logging also had considerable downstream hydrological impacts to these meadows.

Fishery managers and anglers also spent decades moving fish species into the Sierra Nevada. Non-native rainbow and brown trout were planted, crossbreeding with golden trout and preying upon the native fish. Anglers also spent years harvesting golden trout at extensive rates.

Along with anglers, other user groups like hunters, hikers, campers, mountain bikers, off-highway vehicle users and horseback riders all visited the Sierra Nevada in increasing numbers. More visitors meant more impacts to stream habitat and water quality.

Now climate change is bringing warmer temperatures and dramatic swings in precipitation. Droughts extend for longer periods, drying small creeks, heating water and increasing risk of wildfire. Warmer temperature means more rain-on-snow events and faster, earlier snowmelt. When these torrents of water rush through the landscape, it scours and straightens stream channels and quickly flushes from the landscape instead of saturating the floodplain and replenishing groundwater.

The Golden Trout Project

At the turn of the century, concerns over the status and threats to California golden trout led Trout Unlimited to file a petition with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to protect the species as endangered. Over a decade after the ESA petition was filed, the USFWS declined to list California golden trout. Instead, the agency worked closely with the U.S. Forest Service, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and TU to create a recovery plan.

Today, with years of planning completed, the forest service, California Department of Fish and Wildlife and TU are partnering to expand the work of the Golden Trout Project, planning to restore over 40 miles of golden trout habitat across nearly 3,000 acres of the Sierra Nevada backcountry.

Jessica Strickland leads TU’s California Inland Trout Program. She and her team have worked closely with partners and dedicated volunteers to identify the remaining strongholds of California golden trout and prioritize locations in the Sierra Nevada for habitat restoration.

Throughout the process, Strickland has been committed to reaching communities who work, visit and love the Sierra Nevada backcountry. “I’ve tried hard to make sure everyone involved feels like they have a role in this work. We need to think about how others use this place, and how their opinions matter. For example, if I’m going to construct a project next to a cattle grazer’s inholding, I’m going to pick up the phone,” she says. “I want our work to exist in parallel with their needs, too. That’s how we’ll build durable solutions.”

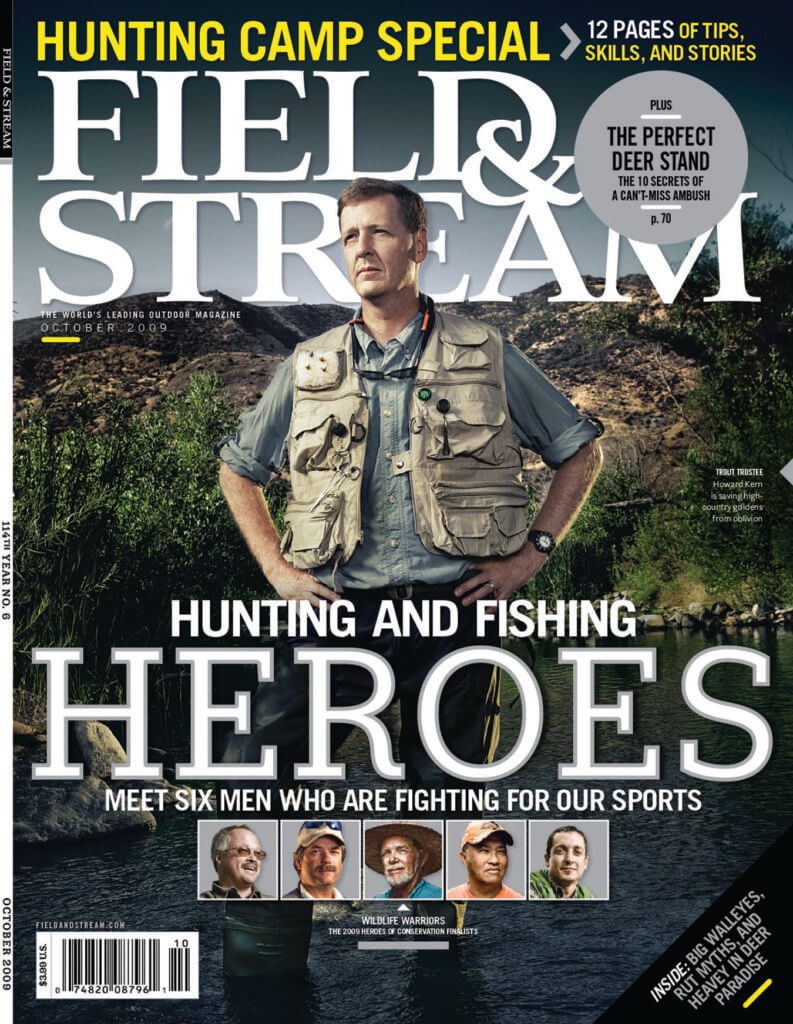

Howard Kern

Today, Jessica Strickland is leading the Golden Trout Project’s work, but she is quick to point out that her opportunity is built upon years of work underway long before she joined TU.

“The Golden Trout Project was defined in the 1980s by the South Coast TU chapter and Federation of Fly Fisher clubs,” she explains. “It was eventually led by Howard Kern, who organized massive volunteer restoration projects in the backcountry for nearly 30 years.”

Kern is a legendary volunteer leader in California. With a lifetime of experience hiking, camping and fishing in the Sierra Nevada, Kern charged into the role, working with agency partners to help build The Golden Trout Project.

One of the Project’s most impactful efforts was a multi-year partnership with scientists at the University of California Davis to identify remnant populations of unhybridized California golden trout. The project organized extensive work in the backcountry and Kern handled complicated logistics. Initially, the core group of volunteers was concerned anglers, but the work eventually captured the attention of other user groups such as mountain bikers, hikers and equestrians.

In 2007, in recognition of their dedication and immense contribution, the Golden Trout Project was given the Department of the Interior’s Take Pride in America award. Two years later, Kern was named Conservation Hero of the Year by Field & Stream magazine for his work on behalf of California golden trout.

When asked about the award, Kern points back to the shared effort. “It was an award given to me, but it really represents the efforts of hundreds—if not a thousand—other people.”

Let the Water Do the Work

During the summer of 2023, years of planning shifted into implementation as the Golden Trout Project moved ahead with restoration projects. In the first phase, work took place in 15 different meadows throughout the Sequoia and Inyo National Forests. Simultaneously, planning for the second phase is underway. For phase two, six more meadows have been identified for restoration.

All told, the work is expected to take a decade or longer. During that time the Golden Trout Project is planning on constructing approximately 2,500 individual Beaver Dam Analogue (BDA) structures to slow down flow of water, reconnect meadow floodplains and recharge groundwater.

The BDAs impound water and sediment, which repairs incised stream channels. By helping to store water on the landscape, they support the growth of willows and riparian vegetation, which stabilizes streambanks and shades the water. The pools created by BDAs are crucial refuge for trout and other species, including endangered mountain yellow-legged frog.

Alongside the restoration work, the Golden Trout Project partners have committed to rigorous project monitoring. They install temperature loggers and groundwater monitoring wells, measure streambanks, take eDNA samples and conduct electrofishing before, during and after restoration work.

Astoundingly, much of this work is done in remote, high-elevation backcountry miles from the nearest road. Half the work sites are in the Golden Trout Wilderness. In designated wilderness, no power tools or motorized vehicles are allowed.

It is grueling work done by dedicated crews, but also creates unique opportunities for shared learning and expanded partnerships. This summer, Strickland and the Golden Trout Project partnered with the Tubatulabal Tribe of Kern Valley to build BDAs on a section of Fish Creek in the South Fork Kern River watershed. During the week, Tubatulabal young adults got firsthand experience working with low-tech, process-based restoration techniques. These skills translate directly to the tribe’s restoration work on their ancestral lands in the Sierra Nevada and to fieldwork jobs with the Golden Trout Project as their ambitious work moves ahead in the coming years.

Comments