This past fall I found myself frequenting the Eklutna River often, after plans solidified for the owners of the Eklutna Hydroelectric Project to briefly return water to the river for the first time since its construction in 1955. The water release was part of the study looking to mitigate the projects impacts on fish populations.

In early September, I visited a location in Eklutna canyon a mile downstream of the dam, at the outflow of Eklutna Lake, that diverts the river’s flow of water. Standing on the edge of the bridge, staring down the dry riverbed, I wondered what the Eklutna River would look like when it was allowed to flow again with the planned temporary water release.

When I returned to the canyon a week later, the soothing sound of flowing water greeted my ears the moment I opened the truck door. The ecosystem was complete again and witnessing the Eklutna flowing at 150 cubic feet per second (CFS) was nothing short of inspiring.

On October 4th I volunteered for a day in the field with staff from Native Village of Eklutna’s Land & Environment Department to assist with a salmon spawning survey. The water release had recently been downgraded to 50cfs so conditions were more favorable for navigating the river and water clarity had improved for spotting fish.

I met Kyle, biologist for Native Village of Eklutna, on a crisp morning. I was to be a second set of eyes on his weekly salmon spawning survey, to experience firsthand reaches of the Eklutna River that were new to me, and hopefully spot Coho salmon returning to the river.

Our survey reach began a rough 30-minute walk from the nearest access point and our downstream walk offered a scenic start to our day in the field. Since Kyle has walked this route weekly for the past 19 weeks, he had the most efficient route picked out through maze of alders. Where the trail intersects a series of beaver ponds, we were met with fresh ice to forge our way through as our wading boots get their first dunk in icy water.

Stepping from the brush and into full view of the beaver ponds, we quickly encountered a snapshot of the composition of life they host. I spotted a bank of swans resting on the first beaver pond, and further off in the brush I picked out the dark bodies of 2 moose cows and 2 calves in the distance mounting a retreat at our arrival. On a nearby rise, not far from our location, we heard the shout of fellow humans greeting us, a crew of scientists who were completing a field trip to orient themselves with the system ahead of preparing terrestrial studies for 2022.

Beyond the beaver ponds, the brush opened up and the scenery is noteworthy everywhere my eyes land. Ahead of me is a fresh perspective of the Knik Arm, behind me a compelling view of the Chugach Mountains and the discernable valley that the Eklutna River carved.

Roughly half a mile upstream of where the river meets the Knik Arm, our work officially began. Kyle and I assumed our positions on either side of the river and begin the walk upstream systematically observing every inch of flowing water for signs of life, using a fish stick (little more than an appropriately sized river side stick) to uncover anything hiding in the depths of pools and structure.

I’m not a hydrologist, but as we worked our way up river, numerous gravel bars and river features leaped out to me as fresh, newly created. Flowing water isn’t just critical to the health of fisheries, flowing waters also help transport sediment necessary to maintain river substrate and habitat health. The flow of sediment downstream on the Eklutna River has been cutoff since the construction of the lower dam in 1929, and the river downstream remains sediment starved, illuminating the recent deposits, many of which were still settling, featuring a quicksand-esque character adding am amusing, tiresome element to our upriver trudge.

Lacking substantial flow for nearly a century, the river’s path was muddled, and its corridor was overgrown. The additional 50cfs was just a splash, but enough for the river to exceed its dwindled route, break its confines in impressive fashion and flood the forest while seeking an appropriate path for the new quantity of flow.

The Eklutna River breaks the confines of it’s overgrown historic channel in search of a new path. Photo: Eric Booton

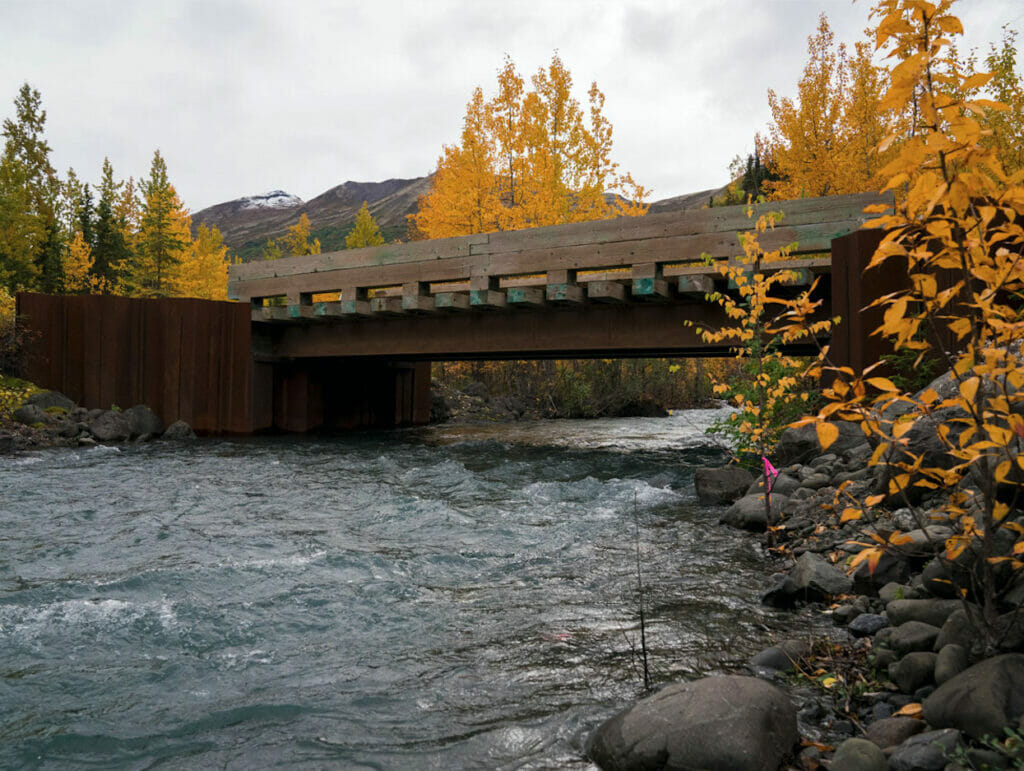

Our fish count was off to a slow start though Kyle and I were thorough in our survey, inspecting every inch of holding water, diligently scanning for movement and spawning colors. It wasn’t until lunch time, and just downstream of the New Glenn Highway bridge, when we encountered our first salmon, and not just one, but a spawning pair. It was a celebratory moment and the first Eklutna River salmon I had ever seen.

Fueled by our riverside lunch and thankful for a moment to thaw our feet, we continued our trip upstream finding multiple more coho paired, individual salmon holding before continuing their own journey upstream, and signs of redds.

Upstream of the Old Glenn Highway bridge, the walls of the Eklutna canyon have seemingly grown around us when we reached the fork where Thunderbird Creek meets the Eklutna River and branch off, following the now isolated 50cfs of the temporary water release up the mainstem Eklutna River.

With significant flowing water absent for nearly a century, the river has decades of work to catch up on and it’s abundantly evident that it wasted no time in establishing a path and beginning the laborious task of moving the tons of sediment, that was stranded behind the defunct lower Eklutna dam, downstream. here is more sediment to be mobilized, a lot more in fact, but the work has begun.

As we reach the remnants of the now removed lower Eklutna dam, the waters impact only mounts, and the fresh carnage is nearly alarming. We surveyed the deep channel carved through the sediment, observed newly exposed boulders pushed downstream, and watched unstable sediment collapse all around us.

Cognizant of the hazardous conditions ahead we walk downstream, returning to the Thunderbird Creek confluence where we turn left to survey Thunderbird Creek for fish before concluding our survey.

Since the flow of the Eklutna River was committed to alternate uses, Thunderbird Creek has been the artery of the river, providing all but a trickle of its life sustaining water. Cold, and crystal clear, it is a change of pace from the sediment saturated water we surveyed earlier. With every step we spook Dolly Varden from their cover and the crimson coho we found were quick to reveal themselves.

Our survey reach terminated at the base of Thunderbird Falls. We paused near the base of the falls and tuned into its power as we listened to its soothing roar. Before heading back to our waiting shuttle vehicle, we stop to say goodbye to the furthest upstream coho we encountered and were pleased to see them paired up and digging a redd with a second coho – that’s one more tally for our salmon survey and the future of the Eklutna River salmon fishery.

Over the course of the survey, I walked more than 5 miles in the flowing river. The Eklutna carved through my dreams that night and the coho we spotted were among the most exciting fish I found this season.

Native Village of Eklutna conducted salmon spawning surveys on the Eklutna in 2002, 2003, 2021 and are conducting studies again in 2022 to provide data on the existing fishery to be considered during the mitigation process for the Eklutna Hydroelectric Project. Prior to hydroelectric development on the river, the Eklutna supported strong populations of all 5 species of pacific wild salmon. This year’s studies were marked with a low number of returning spawning salmon and returning Chum, Coho, and Chinook were all down 80% or more compared to the 2002/2003 numbers. Kyle notes that “while this is definitely disappointing, it is only one year of data and fits with what was seen in other systems in the state, like the Yukon.”

As we have seen with dam and fish passage barrier removal across the country, the resurgence of the Elwha River being a prime example, if you give wild fish a chance, they can create impressive results. In 2020, adult Coho were found further up the Eklutna River than previously ever documented and juvenile Coho had worked their way more than a mile upstream of location of the removed lower dam, all with just a trickle of water. The fish are there, and they are ready, and with water returned and fish passage restored, a bright future is possible for Eklutna River salmon.

Learn more about the restoration of the Eklutna River and find photo/video of this falls temporary water release at EklutnaRiver.org.