How TU staffers in Utah are taking their local landscapes back to the times of mountain men

Rising out of the northwestern Uinta Mountains in Utah, the Weber River follows a serpentine path for 125 miles before making it to the Great Salt Lake.

A couple hundred years ago, this area was prized by mountain men and played an integral role in the global fur trade boom of the 19th century. British trapper and explorer Peter Skene Ogden, for example, led an expedition into the valley now known as Ogden Hole in the Weber Basin from May 16-25, 1825. Over these few days, the expedition caught nearly 600 beavers.

Today, however, the aftermath of losing too many of these valuable conservation critters to the fashions of our ancestors has resulted in several unintended consequences to ecosystems in Utah.

At the forefront of our work to repair this watershed are two TU staff members, Scott Catton and Tanner Cox, who are undertaking a massive effort to help restore this watershed to its former glory after centuries of overgrazing, trapping, mining and other impacts to the local landscape.

“While TU has long been focused on the Weber River, the influx of Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and U.S. Forest Service Keystone Agreement funding is really allowing us to ramp up our efforts to a scale not seen before in this watershed,” said Scott Catton, Upper Weber River project manager for TU. “For example, TU and our partners are planning on constructing up to 2,000 man-made beaver dams on the headwaters of the Upper Weber River by 2025, which is a project scale meant to benefit more than just trout.”

Restoring the Weber by the Numbers:

- Up to 2000 BDAs across 17 locations and 9 miles of river by 2025

- More than $1.8 million in funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

- 100 + volunteers

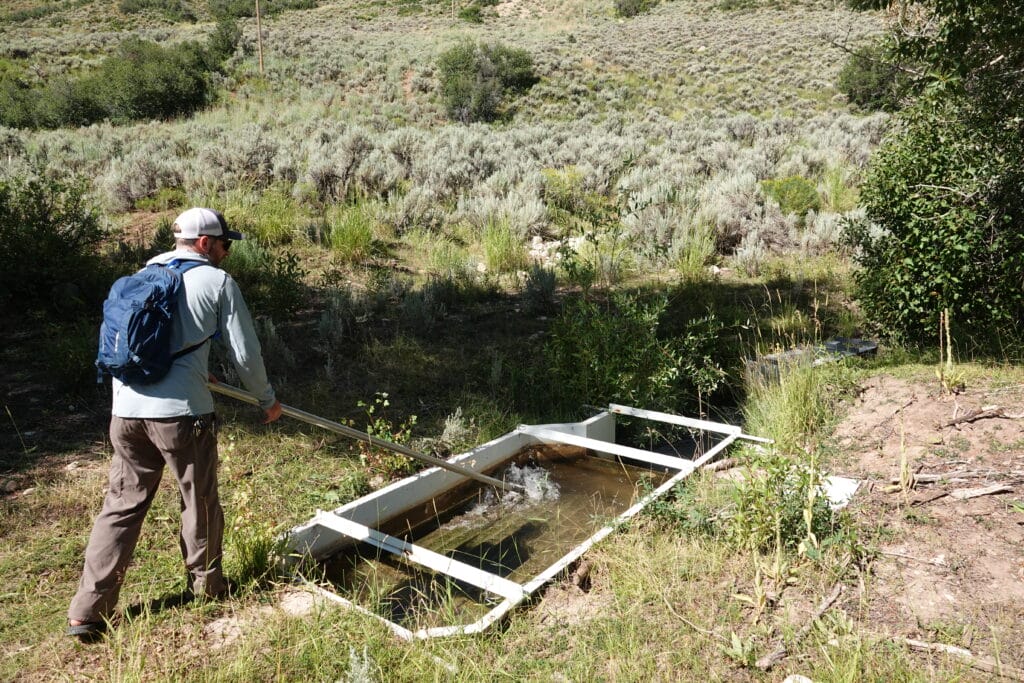

Known as Beaver Dam Analogs (BDAs), these man-made beaver dams are essentially a porous wall of sticks, logs and leaves that slows the flow of water in one part of the stream and retains much of this flow behind the “dam,” allowing some of this backed-up water to seep into the floodplain. This beaver-like engineering helps promote channel aggradation, or in other words, prevents channels from incising into themselves and away from the natural floodplain.

“BDAs are actually very simple and cost-effective structures that provide benefits to both trout and humans alike,” said Tanner Cox, Wasatch area senior project manager. “All we’re trying to do is slow down the flow of water so that the areas adjacent to river act like a sponge and absorb and temporarily store groundwater. This allows for colder and cleaner water to exist during the hottest times of the year.”

The Bonneville cutthroat trout, which is Utah’s state fish and calls the Weber home, is a natural beneficiary of the effort to restore the Weber in the face of increasingly hotter and drier summers across the West. But that’s not where the benefits end; the habitat created by these structures can also act as natural fire breaks and harbor trout during wildfires. By modernizing irrigation diversions, reconnecting key habitats and improving floodplains, the Weber Basin will become more drought resilient and offer local wildlife a more sustainable environment in the face of climate change.

“While the benefits of these simple structures are undisputed, they aren’t a silver bullet to all the problems we are facing in the Great Salt Lake,” said Catton. “At the end of the day, we still need a long run of record snowpacks to help restore the lake’s levels. That said, BDA’s do make the most of our existing water supply in the interim, and we’re incredibly proud to play a role in restoring a watershed that eventually flows into the lake.”

“We’re also lucky to have a number of fantastic partners who understand what we’re trying to accomplish for the entire watershed,” said Cox. “Regardless of whether they are a generational ranching family with private water rights or a government agency, the relationships we’ve built over the years are the secret ingredient to all this work. Everyone understands we are relying on the same water supply and we all have a role to play in its protection and restoration.”

Although the installation of BDAs began last year, hundreds more will be built around October of this year to keep the project on schedule for completion by 2025. Stay tuned for more updates.