Dean Ferguson and his father Dwight have an annual tradition. They drive to Colton, Wash., a tiny farm town perched on a bench above the Snake River in extreme eastern Washington. They place flowers on the graves of ancestors, then drive another few miles to an overlook across a lake.

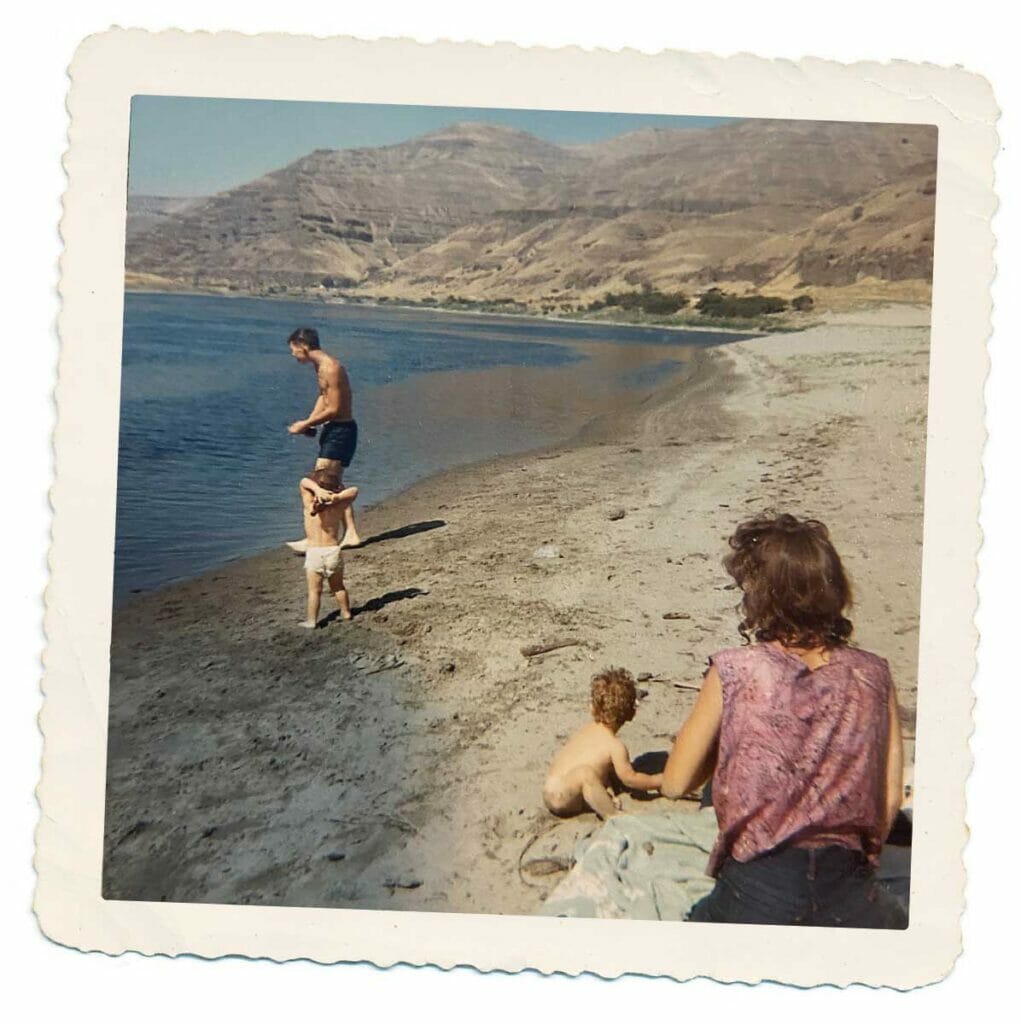

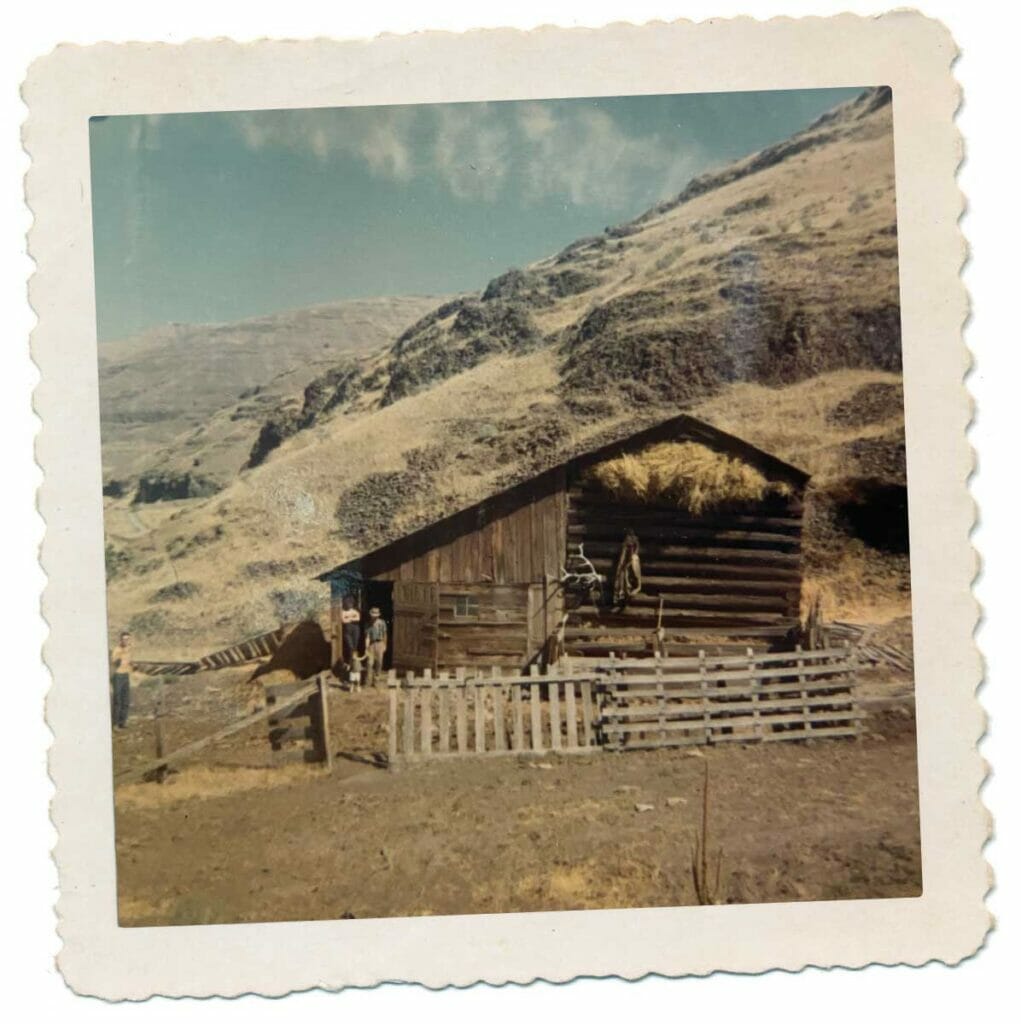

Here 80-year-old Dwight tells his son of growing up in another time, awash in memories of his youth, working beside his father, chasing cows up in the rocks of the high desert along the Snake, playing in the river, eating peaches right off the tree. It is stream-of-consciousness, but it always ends with that lake out there rising, covering, flooding. Dwight gets quiet, a weight suddenly there, heavy, sad, swallowing all conversation. Beneath that lake was their farm, drowned in 1973 by the stagnant, warm pool formed by the last of the Lower Snake River Dams, Lower Granite. Father and son Ferguson sit and think about the barn and the house, the big sandy beach where college kids from Washington State University came to sunbathe and drink beer, the call of killdeer and curlew, the lush bottomland, the community of neighbors and friends farming up and down the river, the peach and apple trees. All gone.

“My family is about as different politically as could be but there’s one thing we all agree on and that’s that the federal government took our land and killed Grandpa Doyle in the process,” said Dean Ferguson. “Of course, I tell my friends in the Nez Perce tribe about it and they are like, ‘Yeah, tell me about it’ and laugh.”

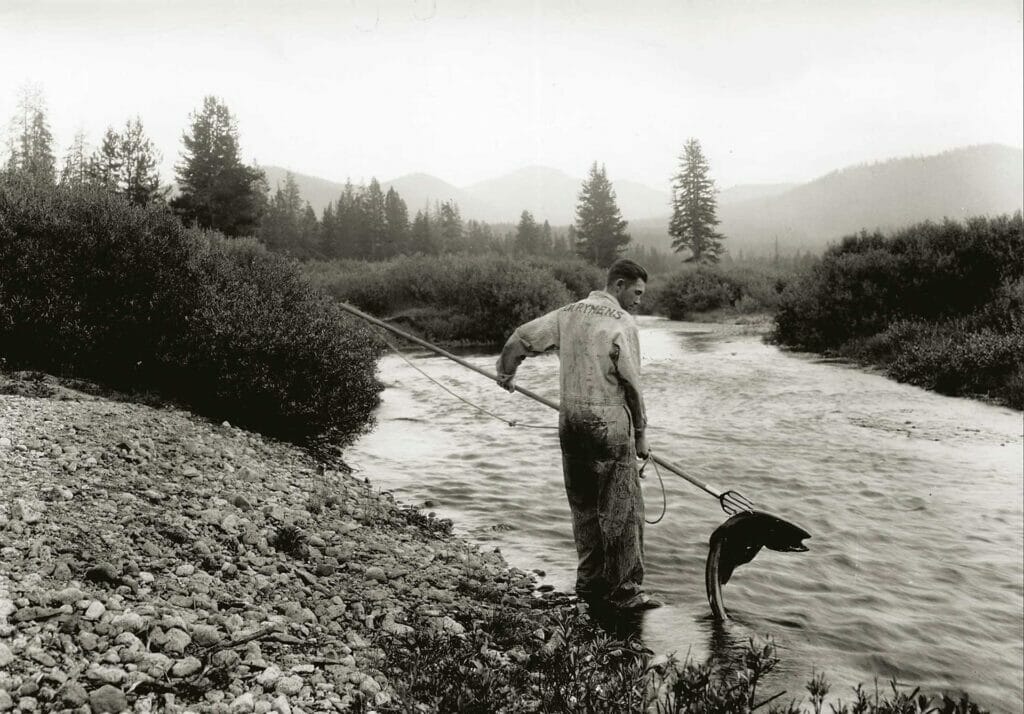

Aside from the native people who had come for thousands of years, the pioneers and then their children and their children came in wagons, then Fords—Model T and Model A. They came with their bare hands, pitchforks, then gaffs and spears, heavy lead-weighted snagging hooks, then egg clusters and flies.

The first Ferguson in the neighborhood, Alonzo, was born in a wagon in 1858 on the Oregon Trail. His is one of the graves that gets flowers on Memorial Day. Five generations of Fergusons have lived and loved, worked hard and died where Washington meets Idaho. They struggled and scratched and built a beautiful little farm. Then the dams came.

The warmwater reservoirs formed by dams of the Lower Snake in eastern Washington drowned 90,000 acres, more than 14,400 acres of which were lush bottomland, a river with vibrant beaches and several communities like Penawawa and Wawawai where the Palouse people had fished for salmon for centuries. This was a free-flowing river with islands and trees, a small shipping industry, and more than 60 rapids with names like Perrine’s Defeat and Gore’s Dread. Gone is all of that. Gone are the 120 acres that bonded the Fergusons to the river and gone is Grandpa Doyle who fought the government and cancer at the same time and lost both battles.

Wawawai orchards, south of Wawawai, Wash., circa 1900 (above), and in 1975 (below) with rising waters after the closing of the gates on the Lower Granite dam.

This is a story of loss. Upstream, in Idaho, the depletion is insidious. Not the creep of rising water, drowning dreams and hard work. More of a slow strangulation—the anadromous fish of Idaho—once a welcome burst like oxygen to eager lung, now a mere wheeze trending toward death rattle.

There is little doubt that the tremendous abundance of the Snake River sustained thousands of native people, but the river also helped early day settlers gain a toehold in pioneer Idaho. A nutritionally fickle land—Lewis and Clark ate their horses in wild Idaho—salmon swam to the rescue every spring and kept swimming into the fall. Salmon fed the ancestors of present-day ranchers on Jordan Creek in Oregon, swimming up the free-flowing Snake into the Owyhee and on to Oregon. Salmon fed Robert Jones’ great aunt on Shoofly Creek and Don Anderson’s forebearers on the Weiser River. Those fisheries winked out when the great migration met the three impassable dams of the Hells Canyon Complex in the 1950s and ‘60s. The Oregon ranchers and Joneses and Andersons, though, all made it work and their descendants live in the region to this day, in part because of the salmon.

Those who were alive during the expansive salmon runs speak of the river as a living, brawling, moving, breathing creature. It changed color when the salmon came, massive schools of Chinook turning the river black, then clear, then black again as another rush of fish swam. Sockeye came and the river ran red.

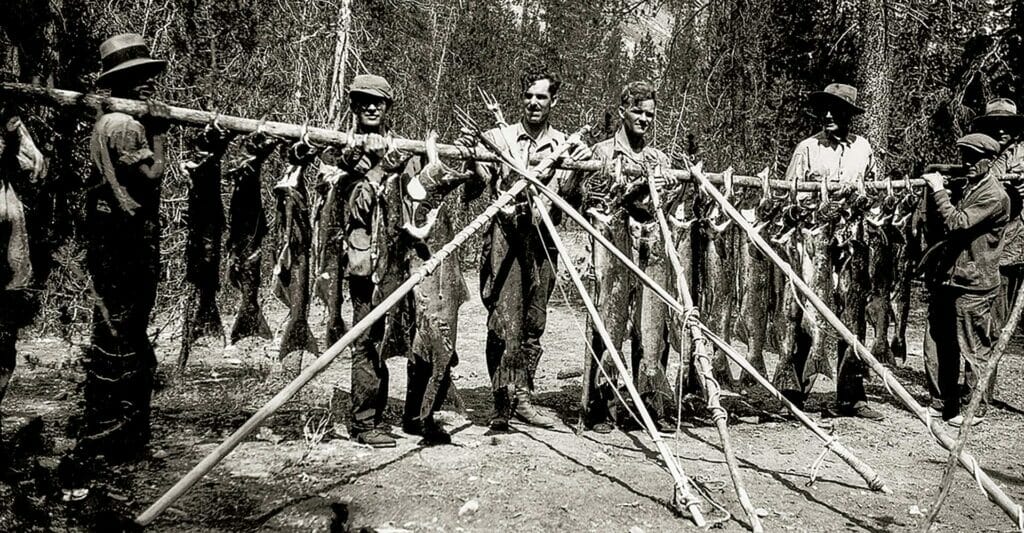

Bill Platts was there. At 93, Platts is one of those vigorous old timers who makes you say, “Boy, I want to be half as healthy as he is at 80.” A track athlete who still competes and defends his world records, Platts was raised in Burley and it was farmers who introduced him to the great salmon runs when he was a kid in the 1930s. Young Platts and a handful of his friends were in charge of chasing the salmon from beneath the banks into the riffles where the farmers could pitchfork them up onto the stream bank. Truckloads of salmon came back every year. “We brought a lot of meat back to the Treasure Valley,” recalled Platts.

The Snake’s primary tributary, the aptly-named Salmon with its many tributaries like the Rapid River, the South Fork Salmon, the Middle Fork Salmon, Big Creek, Marsh Creek, Valley Creek, Bear Valley Creek, Sulphur Creek, Elk Creek, Yankee Fork, the Pahsimeroi and Lemhi was the locus of the salmon culture. Aside from the native people who had come for thousands of years, the pioneers and then their children and their children came in wagons, then Fords—Model T and Model A. They came with their bare hands, pitchforks, then gaffs and spears, heavy lead-weighted snagging hooks, then egg clusters and flies.

The Snake River basin provides more than 50 percent of the coldwater habitat in the lower 48 for Pacific salmon and steelhead. But its rivers and streams are blocked by the lower four Snake River dams, and its fisheries are in rapid decline.

Help us by speaking up today! Tell Congress to take action to remove the lower four dams.

Fantastic fishing for salmon and steelhead from the far Pacific continued in Idaho through the 1950s and 1960s and—not by coincidence—began to steeply decline about the time the last shovel of dirt went into Lower Granite Dam in the early 1970s.

When he was 14 and again 15, Platts and a buddy rode their bikes across a scorching Idaho desert, astride metal-seated one speed bicycles from Paul to Redfish Lake. No helmets, no padded bike shorts, no water to speak of. They drank out of ditches and cattle tracks and they spent a month up in the high country, catching and eating salmon. When they could drive, they turned to an old Ford and started bringing salmon back home to barter and sell.

They were far from the only ones who came into salmon country with an appetite. Fish camps lined the stream banks of the Salmon and its tributaries. Idahoans, deep in the country’s Great Depression, survived on salmon summers. The rivers and streams were rich with them.

“After a while, it got so you couldn’t camp along Marsh Creek, the stench of dead salmon was so unbelievable,” said Platts.

During World War II, the greatest salmon runs of all came, in part due to a scarcity of gasoline which shut down a lot of the travel and shut down the operation of a massive dredge that was busy turning the Yankee Fork River upside down. Still, fishermen made it into the valleys to catch and eat salmon by the thousands. Sunbeam Dam, a remnant of the mining era that had been built across the Salmon River just downstream of the Yankee Fork in 1909 and then partially blown up in the early 1930s, was a focal point where fishermen could stand shoulder to shoulder in hopes of snagging a salmon. So too were many other places. Fantastic fishing for salmon and steelhead from the far Pacific continued in Idaho through the 1950s and 1960s and—not by coincidence—began to steeply decline about the time the last shovel of dirt went into Lower Granite Dam in the early 1970s. Idahoans now mostly take hatchery-raised fish, but even those are in serious trouble because of the dams.

Richard Scully remembers the Snake River much farther downstream in Lewiston where the Clearwater joins as a wide, beautiful river with stunning white sand beaches, a half dozen thriving marinas, and a focal point of a young city. Today most of this is hidden from the city behind riprap and the beaches and the fun that went with them are swallowed by Lower Granite Reservoir. Scully spent his youth in Lewiston, fishing mostly for steelhead and catching big fish on the Clearwater just upstream of town in a hole called Hatwai near where the paper mill sits today. “We were catching big B-run steelhead then, 32 to 36 inches. It was just incredible.”

Scully would go on to get a PhD in fisheries and work all over the world, but he came back to Lewiston to retire in part because of the memories of the river in his youth. Today, those beaches are gone and so too is the thriving riverfront community that was Lewiston before the Lower Snake River Dams downstream. Scully laments the loss of the steelhead and salmon fishery, but also the city of Lewiston’s relationship with the river itself. “There are very few people who remember the riverfront that we don’t have now, people never saw it. We even water-skied on the river.”

Scully, Platts and Bert Bowler are all trained biologists with a keen knowledge of salmon and steelhead and the life cycles of the Snake River. Bowler, the son of famed Idaho conservationist-attorney Bruce Bowler, runs a consulting business called Salmon River Solutions. He believes that if the Lower Four came down, the fishery would come back. “If we rewild the Lower Snake, free it up, the fish will sort it out, it can be done and it can be phenomenal,” said Bowler.

Platts, though, feels the time is upon us and the intestinal fortitude is not. He warns of a “perfect storm” that would be the end of salmon and steelhead in Idaho. With the wrong ocean conditions, the continued poor out-migration of smolts from the high country to the ocean, climate change and a few other factors, Platts predicts the end of salmon and steelhead in Idaho in a decade, maybe two. Hatchery and wild alike. But he thinks it can be turned around.

“We need to do something big. It was big stuff that took salmon—big power, big agriculture—and it’s going to take really big stuff to bring it back. Nobody will do the big stuff. We’ve seen this movie time and time and time again and we’ve seen how it ends. The end point is always the same.”

Bringing the dams down, is that big stuff, he said. Without it, down the drain it all goes.

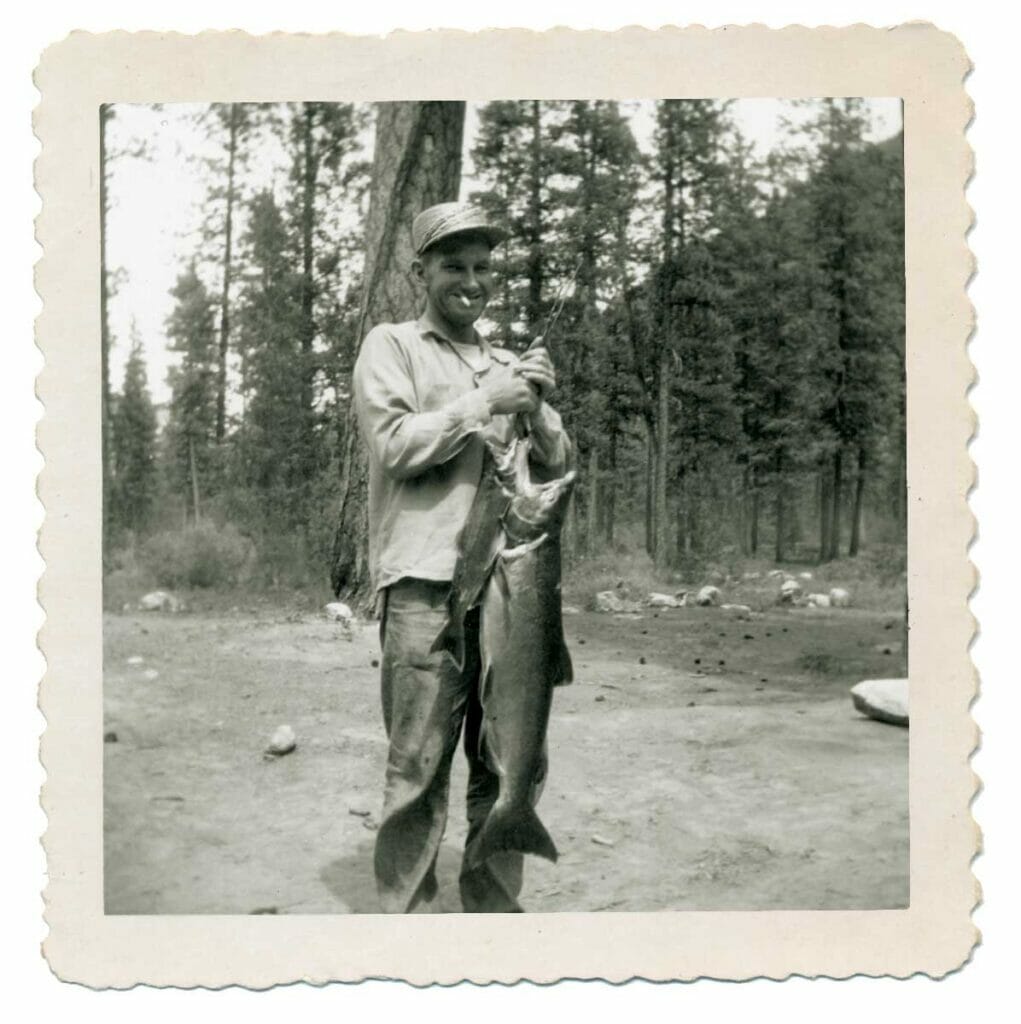

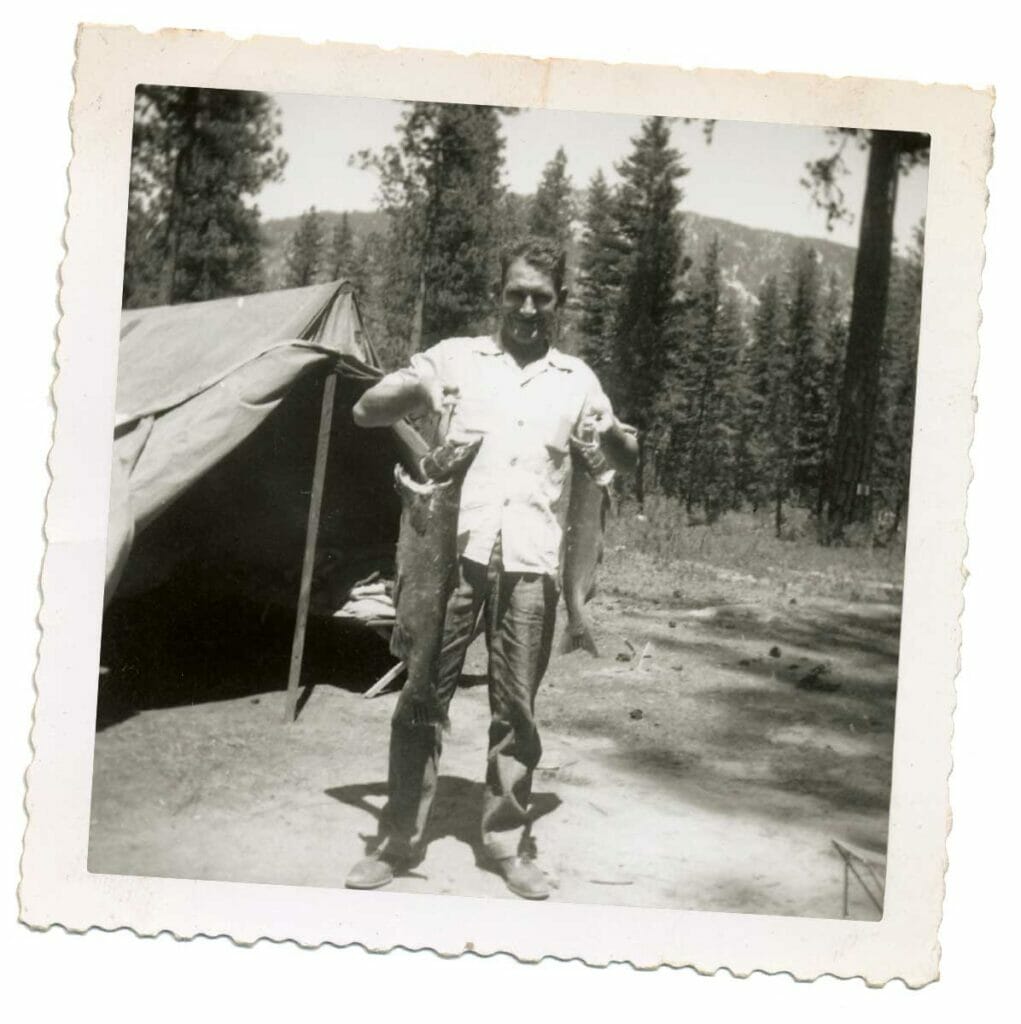

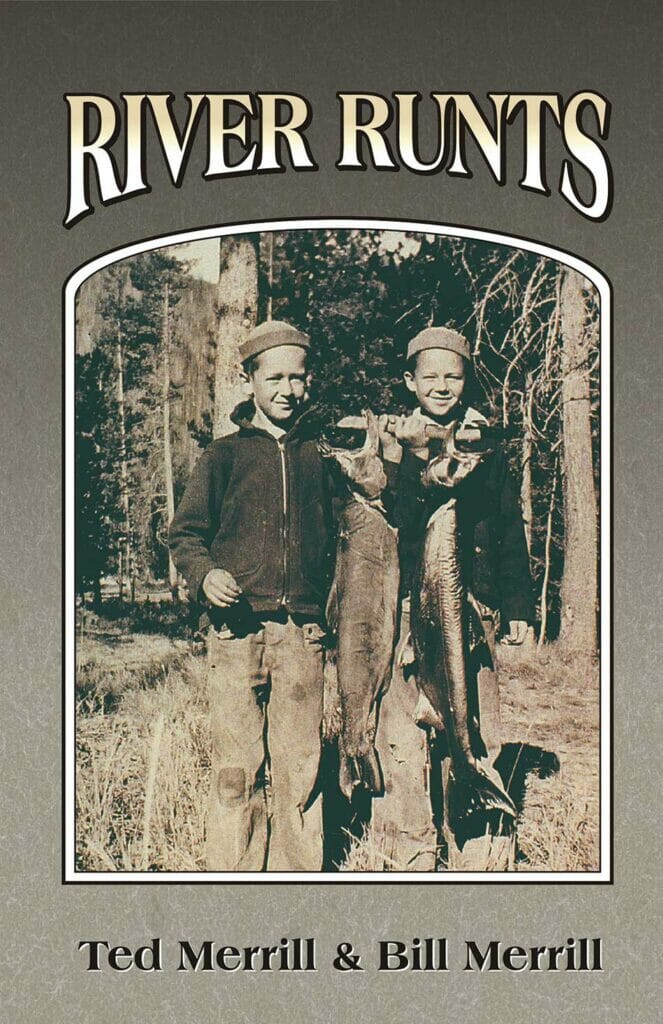

In 2002, two sons of Idaho, brothers in their 80s, penned a book about their youth in wild Idaho, tales of campfire summers and canvas stretched against mountain rain, lanterns hissing the cool night back, Model A Fords grinding up one lane gravel high country passes and down serpentine canyons carved by the endless thrash of water against stone. And tales of fish. Fish galore. The cover of River Runts features the authors, Ted and Bill Merrill holding up two massive Chinook, young lads with smiles earned by outdoor living and the catch. The book gives a glimpse of one family’s Idaho before the Lower Snake Dams took that kind of life away.

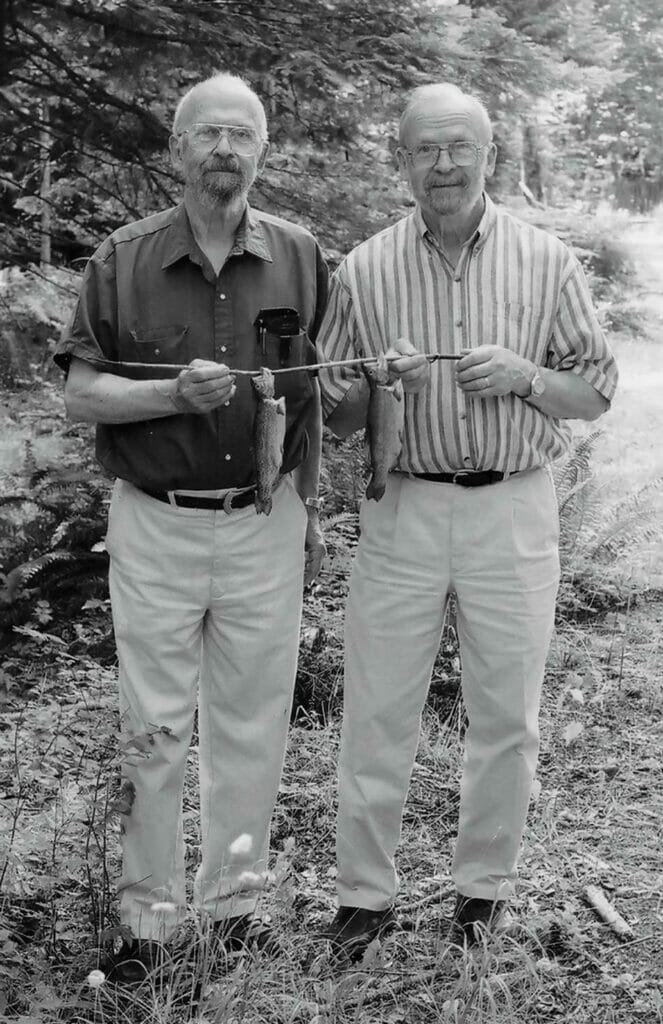

Perhaps the authors intended the very last photo of the book as a sardonic statement, a dry ironic dig at the sorry condition of Idaho’s anadromous fishery, but regardless of intent, it is a palpable metaphoric missive. On the final page of the book, the authors are old men with a life of adventure and success behind them. There in the summer sun decades later they hold two small trout on a willow stick, no massive salmon hundreds of miles from the ocean, just two little trout on a twig.

Neither man is smiling.

Tom Reed is the author of Blue Lines, a Fishing Life. He works for Trout Unlimited.

Comments