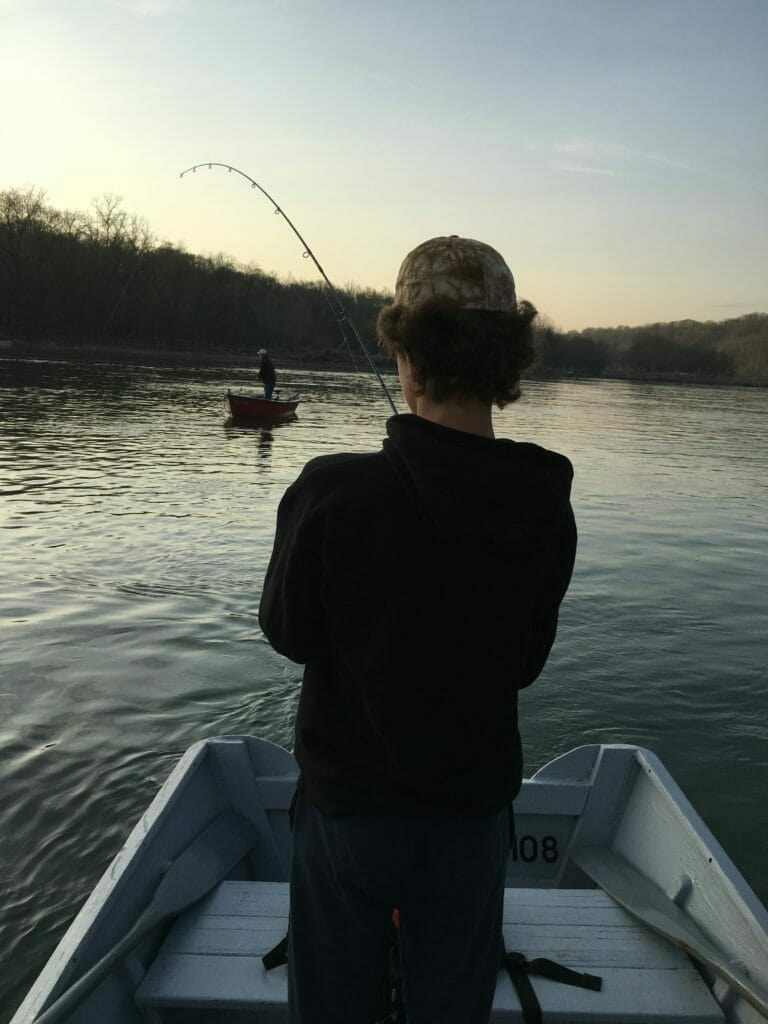

Casey working a hickory shad

“Would you pick Larry Bird or Magic? Who is better Michael or LeBron? Would you take Russell Westbrook or Steph Curry?”

For two hours, every few minutes, the questions came. Casey is 13, and a big kid. He hit a dinger in each of his last three baseball games. We sat in a rowboat rented from Fletcher’s Cove upstream of Georgetown in D.C.—the best urban fishery in the nation—watched the sun rise, and cast for shad; him with a spinning rod, me with a fly-rod. Eventually, I took him to school 20 minutes late, and his principal raised her eyebrows at yet another morning orthodontist appointment.

On the river, we caught fish, watched wood ducks, and several osprey, a bald eagle, and lots of cormorants feeding on the herring moving upstream. Underneath the water hundreds of thousands of shad and striped bass moved from the Chesapeake into the Potomac River to spawn and feed.

When I moved to Washington 27 years ago, you would be lucky to catch a single shad. When my Dad came to Washington, D.C., for school from Newark in the 1960s, he said, “The Potomac was a cesspool, and you would get sick if it touched your skin.” The primary reason for the Potomac’s turn-around is the Clean Water Act. Its passage in 1973 helped to end the discharge of pollutants directly into rivers such as the Potomac. The cleaner water brought the fish back, and the fishermen back to the river.

Over time, the protection of the Clean Water Act for small headwater streams became equally important. These small streams that drain into the Potomac from West Virginia, Maryland and Virginia, some of which only flow seasonally, are like capillaries on the landscape. If healthy, they transport nutrients and gravels downstream. They can be important sources of food and cover for fish. They provide spawning habitat—they’re where big fish go to make little fish.

The Trump administration has proposed to eliminate the protections of the Clean Water Act for these headwater streams—at least 20 percent of the stream miles in the nation, and also 50 percent of our wetlands (but likely much higher on both counts, according to the data our TU science team was able to gather). The streams that would lose protection have a profound effect on maintaining high-quality drinking water for downstream communities.

The administration’s proposal makes losers of the more than one-third of Americans whose drinking water comes from these small rivers and streams that would no longer fall under the protection of the Clean Water Act.

The administration is basing its decision off two Supreme Court cases in the early 2000s. The court split on whether the Clean Water Act should apply to only “navigable waterways” or also include small seasonal streams as it did for the first 30 years of the Clean Water Act. The deciding vote was Justice Kennedy who said that the federal government needed to show a “signifiant nexus” between big rivers and headwater streams.

Well, every angler, including the 300,000 members and supporters of Trout Unlimited, know that gravity works cheap, and it never takes a day off. The significant nexus is formed when enough small streams feed into enough larger streams, then a river becomes navigable. Just as groundwater is linked to surface water, smaller streams are inextricably linked to the flow and health of larger rivers. The administration’s proposal ignores this. It is up to anglers, and all people who care about clean water to save the Clean Water Act.

The administration is accepting comments on this misguided proposal until April 15—next Monday. Please click the link and see how easy it is to exercise your rights to clean water!

One day, but not for awhile, I hope Casey rents a boat from Fletcher’s and rows me and his granddaughter out for shad, or maybe a big striper. Let’s hope the administration has the wisdom to make that possible by protecting the small streams that allow big fish to grow and clean water to flow.

Oh yeah, and Casey, the answer is Larry, LeBron, and Steph.

Chris Wood is the president and CEO of Trout Unlimited.